Double jab, right, hook body, duck, right… Right, left, right, upper, four hooks… Ten straight punches… And ten more… Twenty roundhouse kicks… Now the other leg…

When I tell people that I’ve started kickboxing, they tend to think they’ve misheard. It’s true I’m not who one might think of as a typical fighter. I’ve spent my life working with books and now along with the books I juggle three kids and a dog. The closest I usually get to fighting is when I drag my whippet away from a scuffle in the park, or get elbowed out of the way in the school bake-sale scrum. Although I always seem to have multiple schoolbags looped over an arm, I have minimal upper body strength and have never managed to do a press-up, or even use the monkey bars (I broke my arm mistakenly thinking that I could, aged five). My usual exercise takes the form of cycling at breakneck speed to get to school pick-up on time, throwing a ball for the dog and my walking book club. I have long held hopes of becoming someone who swims year-round, or who runs fund-raising half-marathons, but frankly I’ve had neither the time nor energy. When I attempted a new moms’ fitness class soon after one of the children was born, the soles of my ancient running shoes fell off.

There is always the worry my pelvic floor might not quite be up to the challenge of a hundred jumping jacks

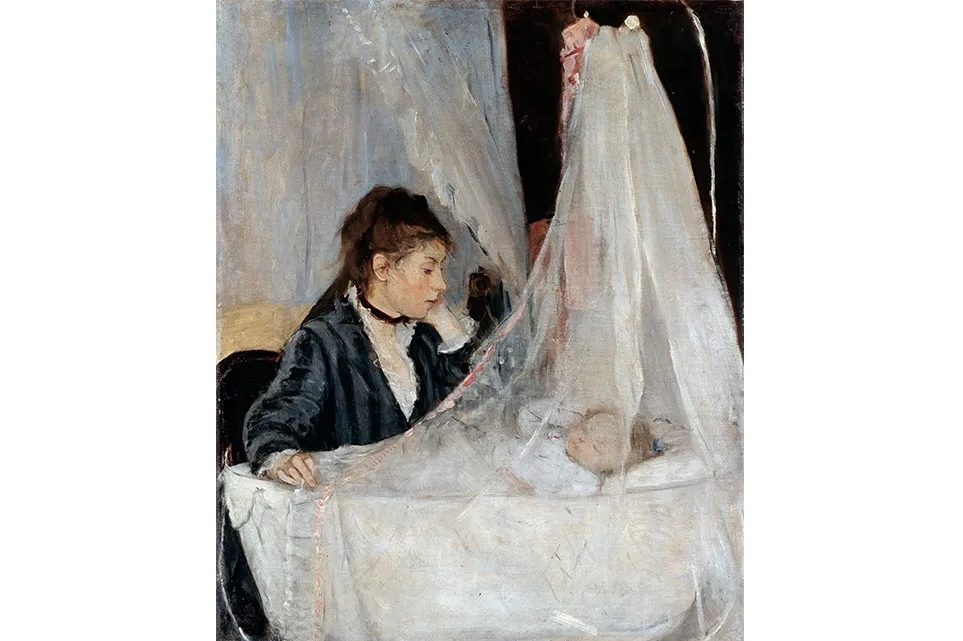

It was, inevitably, a book that made me see that there could be a fighter hiding in the mess of modern-day mothering. My children range in age from four to nine and every Friday for the past year I’ve been taking them to martial-arts classes after school. While the younger two were busy with punch bags and burpees, my elder daughter and I sat on the side reading together while she waited for her class. On this fateful Friday, she was reading Hetty Feather by Jacqueline Wilson and I was in the middle of Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel, a debut novel that went on to make the Booker longlist. This brilliant book takes the form of a boxing tournament; through the bouts, Bullwinkel tells the stories of the eight American teenage girls taking part. Strikingly, the author suggests that fighting is fundamental to femininity. I looked up from the book and watched my daughter tie her belt, readying herself for her class. So where, I wondered, is the fighter in me?

The next week I began one-on-one lessons alongside the children’s group classes. After a grueling warm-up, the gloves and boots go on, and I begin to learn and repeat combinations of punches and kicks. Each week culminates in a final unbelievably long two minutes of nonstop fighting.

Humiliating moments abound. I jog forwards and backwards, knees high, punching into the air, while other parents waiting for their kids pretend not to stare. There is always the worry that my pelvic floor might not quite be up to the challenge of a hundred jumping jacks. Meanwhile, the children sharing the mats are so obviously better than me, learning long sequences and displaying complex moves like spinning roundhouse kicks while I struggle to remember which hand I’m supposed to be hitting with.

But I don’t mind in the least. I’m too busy embracing the surprising discovery that inside me there is a fighter. I’ve learnt that beneath the placid mother who always has her hands full or nose in a book, there is a seam of rage, and here, in the dojo, that rage can flood out. Each thwack of my glove against the teacher’s pad is electric. Boom. Boom boom boom. Out it comes — frustration, anger, fury — and in that moment of release it becomes… power.

“But why are you angry? I don’t get it,” my husband asks over dinner when I tell him about this incredible force that I tap into every Friday afternoon.

Of course there’s nothing really to be angry about: my life is extremely comfortable. It’s just… well, how can I explain that inside my head — and inside the head of so many other mothers and primary carers — is a terrible noise, made up of tiny things that when they all combine become deafening. They are the complicated timetable of recorders and snacks; the water bottles and play dates and laundry; the sheer impossibility of trying to walk along the pavement with children, or to get everyone on and off a bus; the perpetual stress of constantly being late, of having forgotten something, of hating yourself for forcing down spellings or sums or scales. Somehow, when I’m fighting, this senseless, maddening noise turns into a single reverberating note.

As I wonder how to reply to my husband, I realize that although I spend so much of my life wrestling meanings from words, in this instance they fail me. But it’s OK. At least I’m learning to throw a good punch.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.