My mother advised that I get a plain wedding ring. Diamonds, she said, interfere with a woman’s ability to knead dough.

“But I don’t knead dough,” I protested.

“You will when you’re married.”

I guffawed. And yet there I was, four days into my marriage, in an Albanian chef’s Venetian home, being told in no uncertain terms that while my husband Nick could keep his ring on, mine would need to come off.

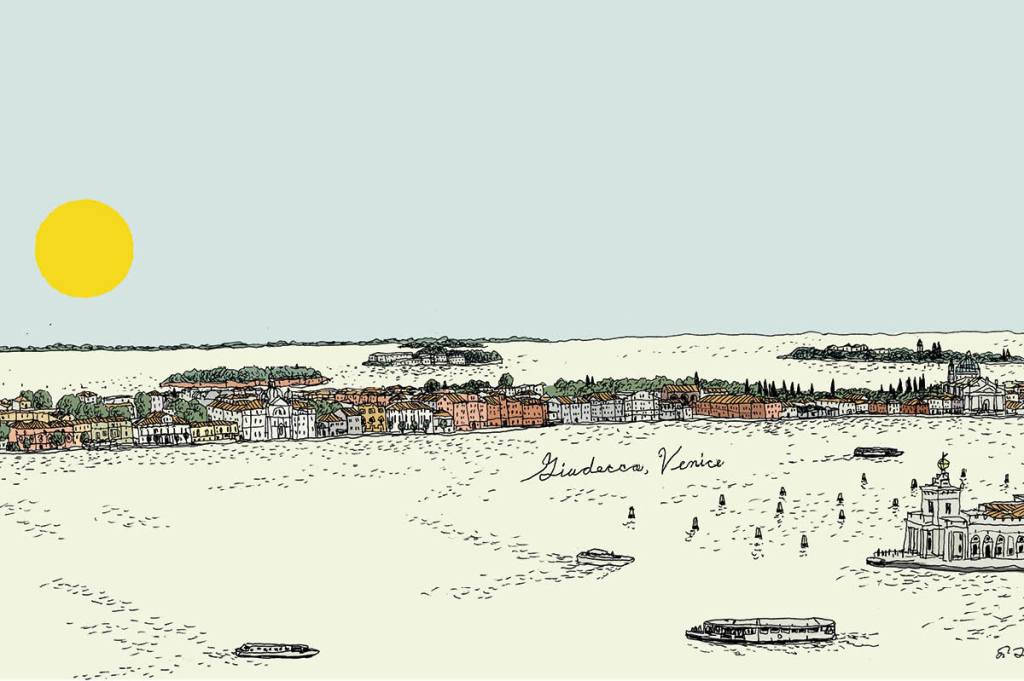

We had arrived in Giudecca, an island in the Venetian lagoon, by water bus, having spent the day in Padova. There, we’d visited the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, home to first-class relics of the great saint — bones, lower jaw, incorrupt tongue and cartilage from his larynx. We had also looked around the famous Scrovegni chapel, which we initially couldn’t find because, much to Nick’s amusement, I had mistakenly been searching Google maps for the nonexistent “Scaravaggio chapel.” We’d packed a lot in and had returned hungry for dinner.

Though originally from Albania, Rosa, our host, has lived in Venice since the early 2000s. Before she offered cooking classes, she worked as a chef for wealthy families. In her brochure, she advertises herself as someone who “loves to be surrounded by nice people who like to eat well and offer free smiles all the time.” February is off-season, so we had her all to ourselves.

Rosa’s home was as delightful as she was. Her front door was behind a wrought iron gate, in a shroud of orange trees and honeysuckle. She greeted us warmly and ushered us into the living room. Her daughter’s violin was on display, and her white walls were decorated with photographs of her clients smiling, busy in the kitchen. Rosa also smiles — a lot.

She gave us our aprons and handed us a card with our menu. All simple Italian classics. To start, her very own “rainbow” dish, baked fruits and vegetables, followed by a selection of homemade pasta and sauces, concluding with tiramisù. We would be assisting with all of it.

Rosa did not speak a word of English, nor we any Italian. Our translator was a tall, distracted man named Simon. Simon seemed an unusual choice. Not so much because of his English, which though limited was clear enough, but rather on account of his tendency to lose his cool whenever he couldn’t find the word he was looking for. “Dis flour is different dan dis flour because. . . because… ohhhh!!” Eye roll, wild gesticulation, abandoned sentence.

Later, we learned Simon was not, in fact, one of Rosa’s usual translators — “Rosa’s angels,” students from the nearby university — but her daughter’s boyfriend. Our translator, Sofia, had gotten on the wrong water bus and was now running very, very late. As we waited for her, we helped Rosa set out the ingredients and drank more Prosecco. The Prosecco in Venice is some of the best I’ve ever tasted. This makes sense, given that the Prosecco region is only an hour north of the city.

Upon Sofia’s arrival, Rosa brought out the fruit and vegetables and instructed us to coarsely chop whichever ones we fancied. The only things to avoid, she said, were mandarins, green apples and bananas. We went with onions, peppers, red apples, kiwis, carrots, celery and potatoes. We gave them a splash of olive oil, and Rosa placed them in the oven at 350 degrees for around forty minutes. The greatest surprise was how much the kiwi — Nick’s choice — added to the other flavors.

For the pasta, there were four choices of flour. We weren’t sure of the difference since Simon had given up translating that part. But Rosa guided us toward the one she thought would work best. We made a mound of flour, then a sort of valley in the middle, into which we cracked the eggs. My ring safely in my pocket, we kneaded the dough into a ball. Rosa covered it in plastic wrap and set it in the fridge for thirty minutes.

We had tremendous fun making spaghetti and tagliatelle with Rosa’s equipment, both electric and manual. We also made ravioli with spinach and ricotta filling, which Rosa had us cut into heart shapes. Rosa, it turns out, is a romantic. She beamed at us, repeating how touched she was that we had chosen to get married amid a world of great uncertainty when so many young people are unwilling to take the leap. Simon had already left by this point.

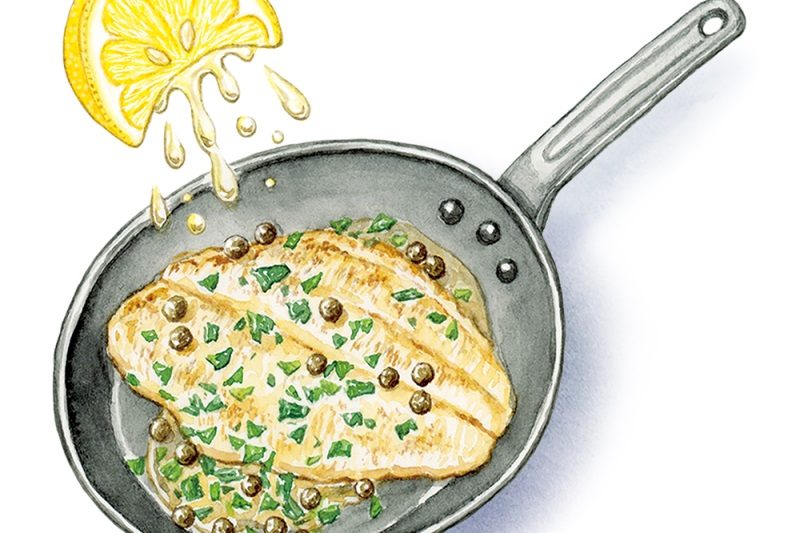

I volunteered to mash the potato for the gnocchi, which we then rolled in semolina flour to stop them from sticking together. Meanwhile, at our request, Rosa threw together a pesto sauce for the gnocchi, cacio e pepe for the spaghetti, and pomodoro for the tagliatelle, even though, she said, tomatoes were out of season. All of it was delicious though, sadly, unrepeatable since neither of us was paying close attention.

Next, the tiramisù. As instructed by Rosa, we separated the egg yolks from the whites, added four tablespoons of sugar, and whipped until stiff. We then mixed in the yolks with two tablespoons of sugar, folding in 500 grams of mascarpone. Dipping the ladyfingers in coffee was harder than it looked. It only takes a split second to render the cookie soggy beyond use. The recipe contains fewer ingredients than I’d imagined. Anyone who puts alcohol in tiramisù is trying to hide something, said Rosa.

It was just as well that the dessert was non-alcoholic, as by the end of the evening we had consumed several bottles of prosecco. The weather was bad, very windy, so we had some trouble getting a water taxi back to the hotel. We were staying just across the water at the Hotel Monaco. Eventually, Sofia managed to get hold of a company that would take us. Nick, who is American, tips generously. Sometimes too generously, from my frugal Scottish perspective. But we agreed both Rosa and Sofia were deserving.

Our evening at Rosa’s was the highlight of our Venice culinary experience, but there were some other notable mentions. One was a charming little “cicchetti” bàcari, Ostaria Dai Zemei, owned by twins (“zemei”) and featuring photos of twins above the bar. We discovered Zemei’s during a food walking tour we did the first night of the honeymoon. “Cicchetti” are basically snacks, a piece of crusty bread topped with meat or cheese, often with some kind of chutney. We had gorgonzola with a chili paste, Manchego with mandarin, and an assortment of prosciutto. All of which went wonderfully with Aperol spritz, a prosecco-based drink, naturally.

Another highlight was gelato at the Gelacoteca Suso. The best flavor we tried was the stracciatella — or “Scaravaggio,” per Nick — which is just fresh milk, sugar, and dark chocolate chips.

We did try some fancier restaurants with more elaborate menus, for instance the Ristorante Grande Canal, but our experience was that they were overpriced and the food not nearly as tasty. Motherly wisdom, it seems, applies to things beyond rings. When it comes to Italian cooking — simple is best.

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.