I have written before in these pages about declining standards in the restaurant world, which has less to do with the food than with the whole “experience” of dining out: the lack of tablecloths, the napkin-wrapped silverware, the to-go boxes, the slovenly informality of staff and customers alike. I stand by every word of it, which is why discovery, or rediscovery, of rare holdout occasions, in this diner-out, is sheer joy.

One such exception, long known to me, Jimmy Kelly’s Steakhouse in Nashville, is exceptional in another sense, too. It has been in operation without interruption and under the same family ownership for eighty-nine years. This is an exceptionally long run in a notoriously short-run industry, and I wonder about the connection between how they have done what they do, and how long it has worked.

Nashville is known worldwide as “Music City, USA,” an affluent boomtown built on the country music, healthcare and education industries. It’s also where, these days, there’s no excuse for having a bad meal. Fancy, or at least expensive, restaurants abound. The frequency of their appearance (and often disappearance) suggests the “let’s put on a show!” spirit of those old Andy Hardy films from the 1940s, with Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland hitting the boards in a spur-of-the moment, flash-in-the-pan production in somebody’s garage, in support of Bundles for Britain or some such rousing cause. In a town of fast-changing fashions, most Music City eateries don’t make it for more than a few years. In recent times, lockdowns and the mysterious labor shortage have only added to the churn.

A long view helps here. For most of Nashville’s history, until the late 1960s, it was a better bet to eat at home than venture out. This is not least because of Nashville’s fourth supporting industry: religion, and religion of a pronouncedly Protestant, anti-alcohol flavor. Nashville was the “buckle on the Bible Belt” long before it was Music City. Temperance and teetotalers in the pulpit did not, of course, mean you couldn’t get a drink, even after the state went largely dry in 1909 and the whole country followed in 1920. It did mean that the sale of liquor-by-the-drink, that fountain of profit, was long denied Nashville restaurateurs who, like good businessmen everywhere, learned to improvise.

Social prohibitions intended to inhibit undesirable behaviors typically create avenues to satisfy them, as the rip-roaring story of Prohibition demonstrated. The opportunity and the challenge of securing reliable supplies of quality spirits for thirsty Tennesseans, over out-of-state and out-of-country supply lines, created, as one of them famously put it, several generations of “honest lawbreakers.” Success in the liquor business required the right mix of prudence and derring-do on one side and lax enforcement by sympathetic officialdom on the other. When it worked, it supported more than a few highly respected Nashville families and several local charities. No longer needing to smuggle, the Kelly family carries on today, still keeping it simple: “A Good Steak and a Generous Pour.” They started early and show no signs of quitting.

The first generation of Kellys fled Ireland during the Great Famine of the 1840s, when their father decided it was better for at least some of his family to risk the perils of the Atlantic crossing than to starve in the old country. Before the two brothers and their sister stepped aboard ship at Cobh, their father pressed into the hands of James, the eldest, a bit of insurance against hard times ahead: a coil of copper tubing. Guard it well, he said; should work be slow in coming, a man who could get hold of some grain and good water could always make whiskey. And whiskey is something a man can always sell. James found his way to Nashville before the Civil War, fought for the South and survived. Afterward, he established an ice company there, married and raised a large Catholic family. Most of James’s customers were saloons and eateries in Nashville’s downtown “Men’s Quarter,” and it wasn’t long before the Kellys expanded into the saloon business too. James’s youngest son John, who had just the right gregarious touch for the business, was father to Jimmy, whose name ended up on the restaurant, and grandfather to Mike, who still runs the family firm today.

During Prohibition, the Kellys bought liquor from Al Capone’s organization in Chicago and ran in more supplies on fast speedboats from the Bahamas, using their ice wagons to quietly deliver spirits to homes in Nashville’s elite neighborhoods. With Repeal in 1934, John Kelly broadened out into the restaurant business proper, in an old two-story house on Eighth Avenue North. He hired the chef from the nearby Maxwell House Hotel and concentrated on doing a few things well: steak, chicken and country ham served by waiters who welcomed customers by name and remembered their favorite drinks and tables. The place had a certain louche classiness: the long German bar was made from a single piece of black walnut; John hired a family friend to decorate the dining room with murals of palm trees, galloping steeds and larger-than-life harem girls. Like the proprietors of New York’s 21, he called his place by its street number: the “216 Dinner Club.” 216 lasted into the postwar period, and in 1949 spawned a suburban offshoot under the supervision of John’s son, Jimmy.

It was this “Jimmy Kelly’s” on Harding Road in Belle Meade, Nashville’s poshest neighborhood, that I first patronized fifty years ago. The place had its own ways of doing things: everyone knew only tourists ate upstairs in the old stone bungalow. Locals knew what was what — they parked around back and dined in the low-ceilinged basement with its exposed water pipes, cedar support posts, knotty-pine paneling and red-checked tablecloths. They didn’t take credit cards, but your check was always welcome.

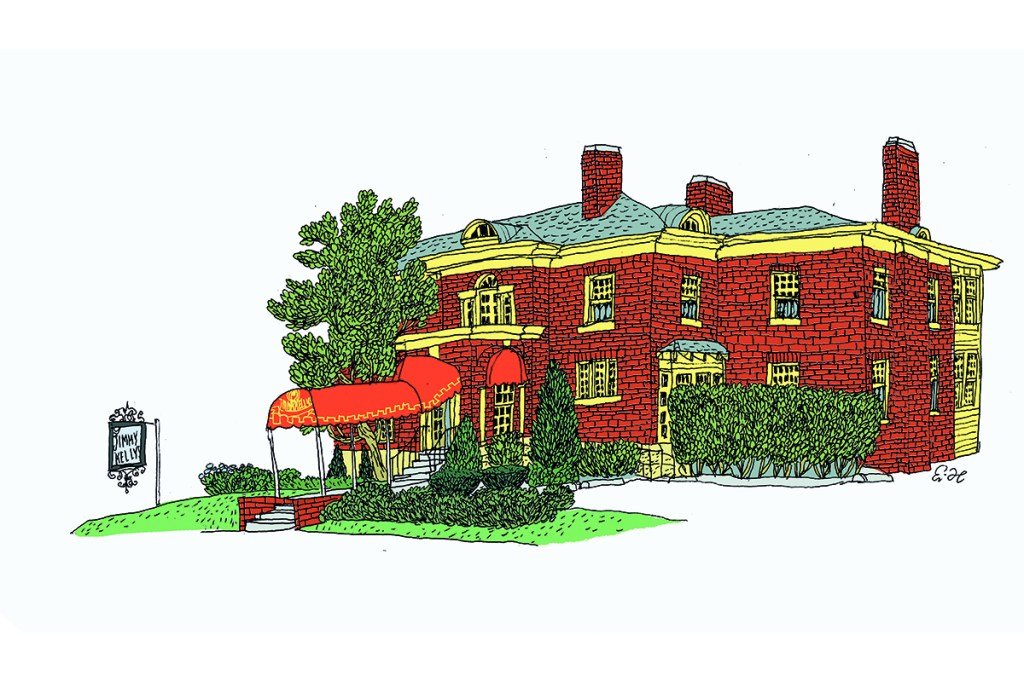

“Jimmy’s,” as we called it, was technically a semi-legal private bottle club: you bought a drink from a bottle that displayed the name of a real person to suggest it was his, but in practice anyone could use it. Friendly law enforcement tended to overlook the ruse, and occasional fines were figured into the normal cost of doing business. With the legalization of liquor-by-the-drink in 1967, raids and fines became a thing of the past, though something of the old speakeasy tone, that authentic whiff of a slightly shady past, lingered on. This was to Jimmy’s enduring benefit and no doubt its competitive advantage. It’s something you could not make up or reduce to a mere brand — the shot of history that came with every generous pour. With the move in 1982 to the old Jesse Wills mansion, built in 1911, Jimmy’s got a more elegant space but gave up nothing of the fine old style.

Eighty-nine years, and counting, is a very long time in the restaurant business. The business-school explanation of such success typically talks about qualities like fiscal discipline, alertness to change and skill at moving with the times. But in some instances, longevity is better explained by steadfastness: when you find work that you can do well, that produces something people will keep paying for, keep doing it.

I can personally attest that over half a century, nothing at Jimmy Kelly’s has changed but the address (once) and of course the prices (steadily). That there is still a Kelly (great-grandson Mike) at the helm has a lot to do with it, but so has the very fact of age itself. In the “new” forty-year-old location on Louise Avenue, this can be observed in the presence of the increasingly rare coat-check, the white tablecloths and well-laid cutlery, the solid wooden armchairs straight from the conference room of an old-fashioned law firm and, not least, the dark paneling and woodwork. I point to this detail in the belief that good woodwork is a signifier of civilization and a marker of cultural integrity across time, a metaphor for remembered ways of doing things that are worth keeping and worth keeping polished.

I like to think that my idea of a great dinner at Jimmy Kelly’s, as it would be tonight and as it was fifty years ago, fits the woodwork. It would go like this: A well-made, generously poured cocktail enjoyed with the buttered silver-dollar corncakes while reviewing the menu; followed by iced shrimp rémoulade, a sirloin or filet steak cooked medium-rare and accompanied with baked potato, creamed spinach and the Nashville classic Faucon salad with onion rings, sautéed mushrooms and grilled tomato as optional sides. There is one and only one dessert: seedy southern blackberry cobbler. Strong coffee and a cognac to finish. Varieties of the grape, including some fine vintages, are also on the card, though in deference to my host’s spirited past I generally stick with the grain.

People don’t drink quite like they used to, which is probably a good thing. I don’t. Still, it is respectful always to order a pour at Jimmy’s, even if you just sip it. As you do, fade back into the woodwork and remember that coil of copper tubing William Kelly gave his son James as he set off for the New World in 1848. What followed was a very American story of risk-taking, hardworking, law-abiding and, when necessary, honest law-breaking entrepreneurs, who came to this country expecting nothing but opportunity, and who succeeded, raised families, sank roots in church and community and served their customers and their neighbors well. And they did so in a line of business that has long given people like me not just a good meal, but great delight.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.