When Lionel Messi won the World Cup for Argentina earlier this month, it not only filled the last hole in his trophy cabinet, it also seemed to end the debate over who was the greatest footballer of all time.

Soccer fans have debated for years about whether Messi was equal to Pelé and Diego Maradona, the two long-standing candidates for one of sport’s most futile and yet most sought-after titles. By finally winning the World Cup, fans and pundits the world over ruled en masse; Messi was now the greatest.

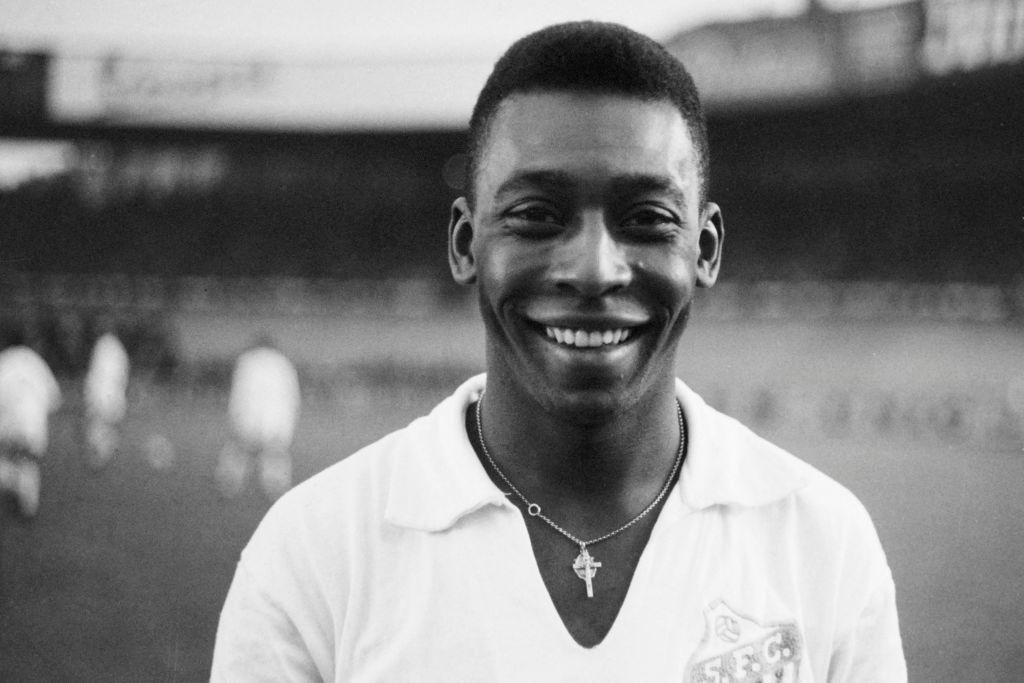

Pelé’s death on Thursday will reopen that debate and hopefully give pause to those who have sided with the Argentine magician. Because recency bias, social media, television and association football’s unquestionable Eurocentricity have all amplified Messi feats and diminished Pelé’s.

For years now, keyboard warriors and pundits who should know better have belittled the Brazilian with series of tiresome charges. He never played for a European club (even though Brazilian soccer was the best in the world in Pelé’s day); hundreds of his goals came in friendly matches (too easy); he declined to lead the fight against both racism in Brazil and his country’s military dictatorship (Pelé was always non-confrontational); and he won many of his medals surrounded by other legends (too much help).

People who rate Messi (or Maradona) as the GOAT are no doubt true soccer fans. But it’s an easy choice. Messi’s brilliance is there for all to see, all the time, in HD from twenty-four camera angles, on television, YouTube and social media.

In comparison, not all of what Pelé did was recorded and the footage that has survived is mostly black and white, frequently grainy and almost always incomplete. Pelé scored 1,281 goals but only around half of them are on tape and fewer still in color. It’s as if we have all of The White Album and only scratchy recordings of “Yesterday” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Explaining his brilliance and originality to people who only saw a few clips online is like asking someone with Spotify to appreciate the wonder of the gramophone.

Those who rate Pelé the best are more than soccer fans, they are scholars, too, because to understand his greatness requires work. I never saw him play so I don’t know how good he really was, goes one lazy and oft-repeated explanation. Research resolves that problem. Books, videos and contemporaries are all clear: Pelé was the King.

Of course, making it to the top is harder now. Soccer today is faster, more competitive and the demands made on players are infinitely greater, both on and off the field.

But it’s easier, too. When Santos went to Europe, they often slept on overnight trains to get from one match to another. In Brazil, a nation bigger than the continental United States, they took the bus or endured long flights on rickety planes. They ate chocolate and apples to keep up their strength. There were no nutritionists, podiatrists, soft tissue therapists, data scientists, video analysts or mental performance coaches to help them prepare or recover.

The pitches in Pelé’s time were muddy and uneven. Tackles from behind were common and brutal. With no cameras on every corner, much less VAR, players could spit and punch and kick and they did, often, and with impunity. And it’s easier to stand out when wearing boots that are softer, in strips that are lighter and kicking balls that are rounder.

Pelé also improved without the aid of one constant competitor. Most sporting greats are motivated by a rivalry. Messi has Cristiano Ronaldo; Ali is immortal in large part because of his fights with Joe Frazier and George Foreman; Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic can all lay claim to be the greatest because they have each other.

Pelé was running superfast laps without a pacemaker. When rivals did appear, legends Ferenc Puskas, Alfredo di Stefano, Bobby Charlton and Franz Beckenbauer among them, Pelé left them trailing.

‘Eusébio is a chapter, Pelé is a compendium,’ Real Madrid president Santiago Bernabéu once said when someone dared compare Pelé to the Portuguese star.

The young and global audience who watch football today are either unaware of these facts or glibly dismiss them. In today’s self-obsessed world, all that matters is now.

Sadly, now Pelé is gone. But his memory must remain.

The King is dead. Long live the King.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.