In the summer of 2020 I was awarded a degree in history from Bristol University — the culmination of three years’ work, late nights and great expense — but it is my concrete pump operator license which sits above the mantelpiece. My father considers my ability to pump concrete at a rate of one cubic meter per minute to be far more impressive than my knowledge of Henry VII’s foreign policy.

At university I worked as a pump operator for my father’s piling company, making me a very unglamorous nepo baby. I helped bore the foundations for construction all over the country. On a job installing disabled-access elevators at Old Trafford stadium, the foreman explained to me that the piling gang is much like a soccer team: the pump man is the center half, threading passes (concrete) through the midfield (snaking pressurized pipes) toward the striker (piling rig), which attempts to break down the opposition defense (the often wintry earth) with our attack (rotating steel auger). As the steel cage was lowered into the concrete-filled hole, we would often shout: “Aguerroooooo.”

Concrete is a perfect building material. It is the second most-used substance in the world — after water — and its production has changed little from when the Romans were mixing volcanic material with cement. Innovation rarely happens — and when it does, it is often for the worse.

Take the recent debacle over reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC). More than a hundred British schools, and thousands of other buildings, are compromised by “bubbly concrete” which was used in floors, roofs and walls between the 1950s and 1990s. It was popular because it was cheap and quick to install, essential for meeting postwar demand for new buildings. It’s also very bad at its job. The cavities inside RAAC’s structure make it weak and susceptible to water leaking in, which in turn can cause the steel reinforcement inside to rust and fail.

Any competent concrete pump operator knows that bubbles are bad news. I used to spend many enjoyable hours hiding in the toolshed, casting a series of test “cubes.” I would set concrete in molds and use a tamping rod to knock out any bubbles, allowing it to form a smooth, dense block. The cubes were then tested at different loads and over different time periods. It was an important job and I liked to boast that none of my cubes ever failed. All the buildings I worked on are thankfully still standing.

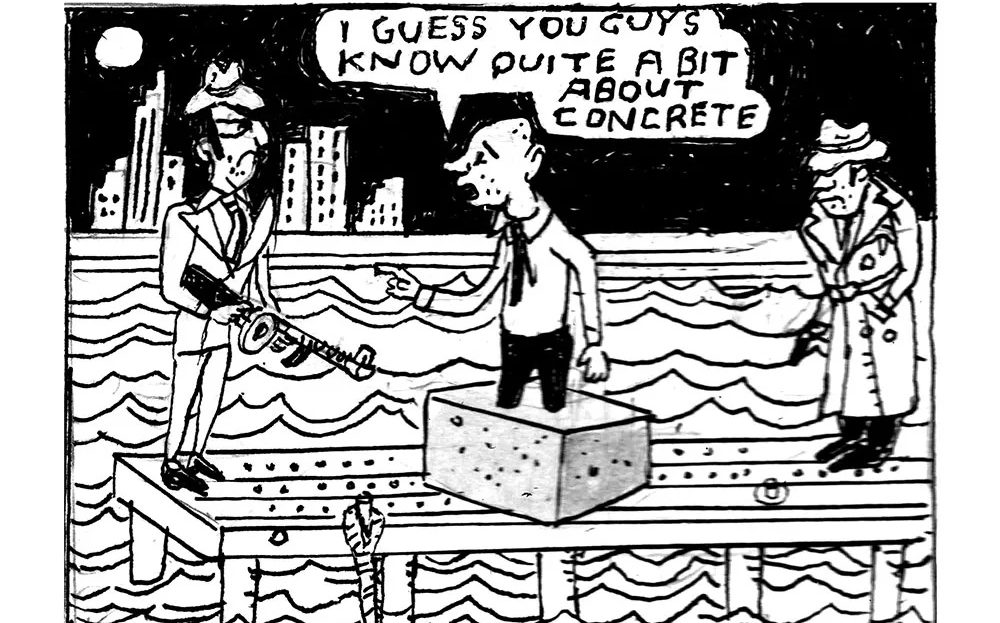

Concrete is more than a mixture of aggregate, water and cement. On a building site, concrete is an emotional subject. We would talk about its spiraling price or complain about the burning sensation when it meets the skin. When I started in construction, I would be greeted each morning with a sly, “here comes the eye candy” — and my bright, unsoiled hi-vis outfit made me stand out. But after six months wallowing in concrete slurry, it was plastered all over my overalls and hair, and I was part of the gang.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2023 World edition.