At first glance, it looks like any other sleepy village in southwest England. A medieval church and manor house face a fish ’n’ chip shop and post office across the green. There’s the obligatory pub, the Farmers Arms, where log fires crackle and ale-taps gleam beneath oak-beamed ceilings. Along the narrow lanes, whitewashed cottages peter out into rolling Devonshire hills. In true UK style, the place even has an obscure tongue-twister of a name: Woolfardisworthy. Population 1,123.

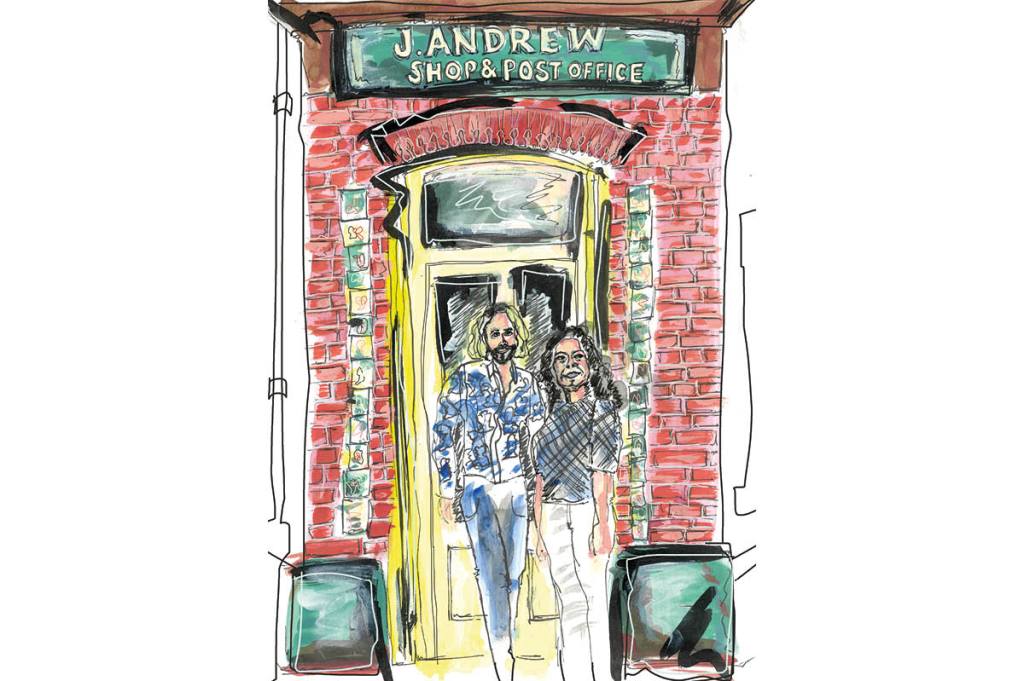

Look closer, however, and you’ll realize this isn’t your standard British backwater. For every pint of cider being poured in the pub, there’s a craft cocktail infused with foraged botanicals and homemade cordials — think a crabapple cider margarita or a sea buckthorn gin sour. The village store may look the retro part with its checkerboard floor, art nouveau tiles and old-school signage proclaiming “J. Andrew Shop & Post Office,” but its shelves are stocked with goods from ethical, indie food brands (ancient-grain pastas from Fresh Flour Company, Citizens of Soil’s small-batch, female-made olive oil). Everything from teabags to dog treats is locally produced. Several rooms above the shop, plus three nearby cottages, contain luxurious self-catering accommodation, their underfloor heating and rainfall showers banishing stereotypes of drafty country digs. The Grade-II listed Georgian manor is currently being converted into a boutique hotel.

It wasn’t always this way. Rewind a decade or so and the Farmers Arms sat vacant, its dilapidated thatch sheathed in tarpaulin. Brain-drain — the phenomenon of young people abandoning rural communities for urban centers — skewed demographics so much that the village school had barely enough pupils to keep running. Woolfardisworthy (or Woolsery, its nickname, far easier to pronounce) had turned from idyllic to ailing, left behind by the inexorable march of globalization. It’s a familiar story for many small, rural towns, both in my native Britain — where around 500 pubs and 400 village stores close each year — as well as across the pond and beyond.

The difference was that this village held special significance for Michael Birch, who together with his wife Xochi founded the now-defunct social networking site Bebo. Birch spent his childhood summers in Woolsery and returned at least once a year ever since. Six generations of his family are buried in the churchyard. His great-grandfather even built the corner shop. After they’d made their fortune in San Francisco — Bebo was sold to AOL for $850 million —word reached the Birches in 2012 that the beloved village pub was going to be turned into apartments.

“We knew if this happened there’d be no turning back,” Birch says. Buying and renovating a humble boozer, he recalls, “sounded like a simple thing to do at first. The project snowballed, though.” Other local businesses that had fallen on hard times came forward with offers to sell. Before long, a multihyphenate endeavor — a 150-acre organic farm, artisan bakery and butchery joining the chip shop, village store and post office — was born and christened “The Collective at Woolsery.”

Simply landing a gastropub or boutique hotel in a rural community isn’t exactly original, nor helpful to residents, if the profits from affluent guests simply line one landowner’s pockets. But Birch’s vision is far more holistic and public-spirited. “We wanted to create a destination experience very different to staying in a large country house within its own grounds,” he explains. “Our goal is for Woolsery to be a sustainable village that can economically secure its own future. To create new jobs around hospitality and farming.”

There are echoes here of Italy’s albergi diffusi (“scattered hotels”) in which neglected buildings dotted around villages are turned into tourist accommodation. Champions of this model say it not only rescues abandoned properties but also encourages patronage of small local businesses, rather than inviting visitors to stay holed up in a resort. The piazza — or village square, in Woolsery’s case — becomes the lobby.

Here in North Devon, agriculture and its supporting industries were once the economic lifeblood. Which means Birch Farm is perhaps the Collective at Woolsery’s most vital and ambitious element. A few minutes’ walk from the village center, I find head ecologist Josh Sparkes tending to the beginnings of a 300-species edible forest. “Agro-forestry is the future of our food consumption,” he says, explaining how its ground covers, fruiting bushes, vines, low-canopy fruit trees and high-canopy nut trees will knit together, providing year-round sustenance and more biodiversity.

It’s the antithesis of Big Ag. And compared with Birch Farm’s exuberantly leafy plots and orchards, the fields of neighboring farms appear homogenous and preternaturally green. “We don’t want to be sterile and neat,” Sparks shrugs. “We want slugs and weeds.” Behind him, an unassuming outbuilding houses a formidable fermentation lab, where seasonal ingredients are preserved as syrups, cordials, oils and pickles. The jars’ contents range from whole bulbs of garlic to parmesan rinds to pineapple weed. Sparkes is also reintroducing native livestock breeds and growing indigenous substitutes for sought-after flavors — lemon balm stands in for Mediterranean-grown citrus fruits, the savory-flavored leaves of beef and onion tree are used to wrap sushi instead of nori.

Over at the Farmers Arms, executive chef Ian Webber turns the produce into inspired gastropub fare. Depending on the season, the menu might offer cured hogget with pickled cucumber and lemon-thyme honey, wild garlic dumplings with penny bun mushrooms or mussels from the near- by Atlantic coast in local cider and cream, followed by a mugwort and geranium trifle. Breakfast hampers, delivered to guests’ doorsteps each morning, contained rhubarb cordial, sweet-clover yogurt, nettle fritters with poached eggs and smoky bacon beans during my stay.

Birch Farm provides sustenance not only to the Collective’s own businesses, but also to the wider community. There’s an affordable veg box scheme and the farm collects villagers’ kitchen waste (for composting) in exchange for fresh produce. It runs woodland education programs at the village school, teaching kids about healthy nutrition, food systems and biodiversity. The ambition is to eventually create a fully self-sufficient and circular food system.

It might seem an incongruous next step for a tech tycoon, but Birch sees a common thread. “Other than of course providing the funding, our passion has always been building communities and hospitality, and for us it just so happens that journey started in Silicon Valley.” The couple grew Bebo to an online community of more than 10 million people, then switched to IRL gatherings with the Battery, a private members’ club in San Francisco.

“We often spoke about the club being to the city what a pub is to a village, that central community hub to bring people together,” he says. “Of course, a thriving community is so much more than just a pub, but it’s one of many building blocks, all working together and interplaying. Being greater than the sum of its parts.” He hopes even more independent businesses will pop up in and around Woolsery. Local people are hired wherever possible, but it’s also about drawing fresh talent and their families to the area, by showing it’s possible to succeed in this setting.

Admittedly, Woolsery’s not the prettiest village in these parts — neighboring coastal Clovelly boasts the postcard-worthy looks — but all the more reason to cultivate an alternative appeal; less quaint, more future-facing. Visitors can get involved in the Collective’s worthier aspects (personally, I loved nerding out about climate-resilient crops on a farm tour with Sparkes), or simply savor a proper Sunday roast and Devon-brewed pint beside the fire.

It’s heartening to see the pub bustling even on a winter weekday night, well-heeled weekenders rubbing shoulders with locals. Notwithstanding a few grumbles about building-work disruption or house prices rising, most villagers seem on board with the Birches’ developments. Perhaps it’s because, behind the immaculate design and trendy menus, Woolsery, crucially, has something missing from many rural communities: a whiff of optimism in the country air.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply