A friend of mine, a lawyer of radical disposition who typically defends nuns who pour blood upon weapons of war, or peace activists who trespass upon military installations, recently told me of his latest case. He is representing a young person who defaced a statue depicting a Confederate soldier.

I told him that while I usually applaud his vandal-defendants, I am not in sympathy with this one. The answer to monuments of which one disapproves is not destruction or removal or whinging about your hurt feelings, but rather the creation and emplacement of new monuments. I don’t mean glorifications of dead politicians or military figures — we’ve had enough of those to last a national lifetime, thank you. Rather, how about honoring local artists or athletes or musicians or just ordinary folks whose benevolence or kindness or generosity brightened their little corner of the world?

History: it’s not made by great men, as my favorite commie band sang. When the Ku Klux Klan paraded down Batavia’s Main Street in 1923, the men of St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church, among them my Irish ancestors, stood in the street and refused to let the Kluxers pass by. (The northern Klan of the Twenties was primarily anti-papist: our town had very few blacks or Jews.)

No one was killed or even seriously injured in the faceoff. None of those involved posted selfies on social media, and neither side bused in itinerant goons bent on mayhem.

I suppose this clash doesn’t rise to the level of historical marker-worthy, though I do like the peaceful denouement. The Klan disappeared shortly thereafter, and presumably its local members — I have seen the list — took up more wholesome pastimes. The town turned plurality Catholic thanks to philoprogenitive Italians. Some of my Catholic foremothers married Protestants — not Klansmen — and amity reigned.

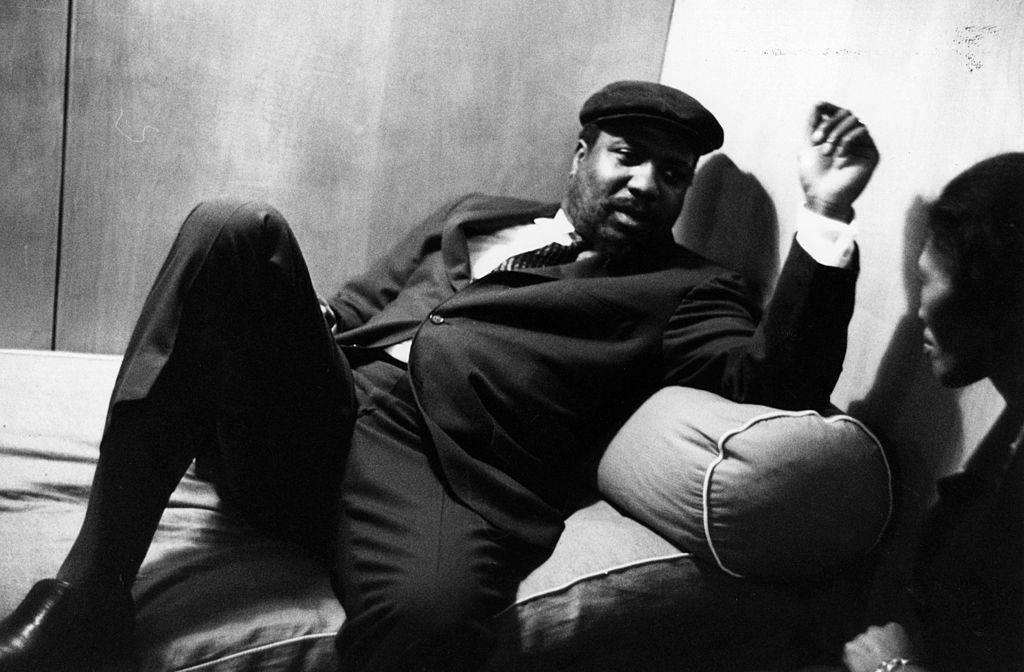

In that same year, a little boy named Thelonious Monk came to town, and almost a century later he’s at the center of my latest plan to splatter culture all over our sidewalks. Monk, who grew up to be a jazz pianist and composer of exquisite inventiveness and cool, was a Fresh Air kid: that is, a New York City boy who rusticated in the summers with host families in small Upstate towns, away from Gotham’s oppressive grime and its taunting skyscrapers that block the stars.

In the summer of 1923, five-year-old Thelonious boarded a train with 50 or so boys of all colors and creeds who would spend two weeks hereabouts. Upon arrival the energetic Monk made an immediate impression: he was chosen mascot of the fire department, the plummest of honors. The precocious lad was given a uniform, permitted to ring the bell, and at the end of his two-week sojourn he vowed to return someday to become a real fireman.

The fire captain told the local paper, ‘He’s the nicest little gentleman you’d ever care to see. His mother certainly brought him up right… I never heard any bad language coming from his lips. Another thing, Thelonious always says his prayers. Yes, he’s brought up right.’

Young Monk returned the next summer. A fireman walked down to the welcoming party for the children and asked the chairwoman of the local Fresh Air committee — the grandmother of our late and dear friend Peter Mumford — if he might escort last year’s mascot to the firehouse. ‘You see,’ he said, ‘we have all been mighty anxious to get [Thelonious] back and the boys can hardly wait until they see him.’

For the rest of his stay, Monk had the run of the station. A later Batavia newspaperman, Mark Graczyk, wrote, ‘It’s an amazing story — an African-American child befriended by a fire department composed entirely of white men who had perhaps never met a black person before.’

Worth remembering, perhaps?

The mural painted on my envisioned Thelonious Monk Alley would feature images of little Thelonious in his fireman’s cap, surrounded by firemen, and the adult Thelonious at the piano. But I suppose we’ll have to settle for the childhood image to be just the boy — Thelonious straight, no chaser.

For although in later years Monk spoke fondly of his Batavia experience, I expect the professionally aggrieved would find the image patronizing. As if the little white boys who served as mascots in other years were treated as equals by the firemen!

Thelonious Monk deserves the last note. He once told his manager, ‘When I was a kid, some of the guys tried to get me to hate white people… and for a while I tried real hard. But every time I got to hating them some white guy would come along and mess the whole thing up.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2021 World edition.