Provence

Molly MacCarthy launched the Bloomsbury Memoir Club in the spring of 1920 with two aims. The first was to bring together the old Bloomsbury set who’d been dissipated by World War One and the second was to encourage her dilatory husband, Desmond, to write his memoir. She was successful in the first but not the second. The original club was composed of old friends and family members: the MacCarthys, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Vanessa and Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, Roger Fry and John Maynard Keynes. The aim was “serious but also to amuse.” There were few rules, “one of which was that no one should be affronted by anything read or said in the Club.”

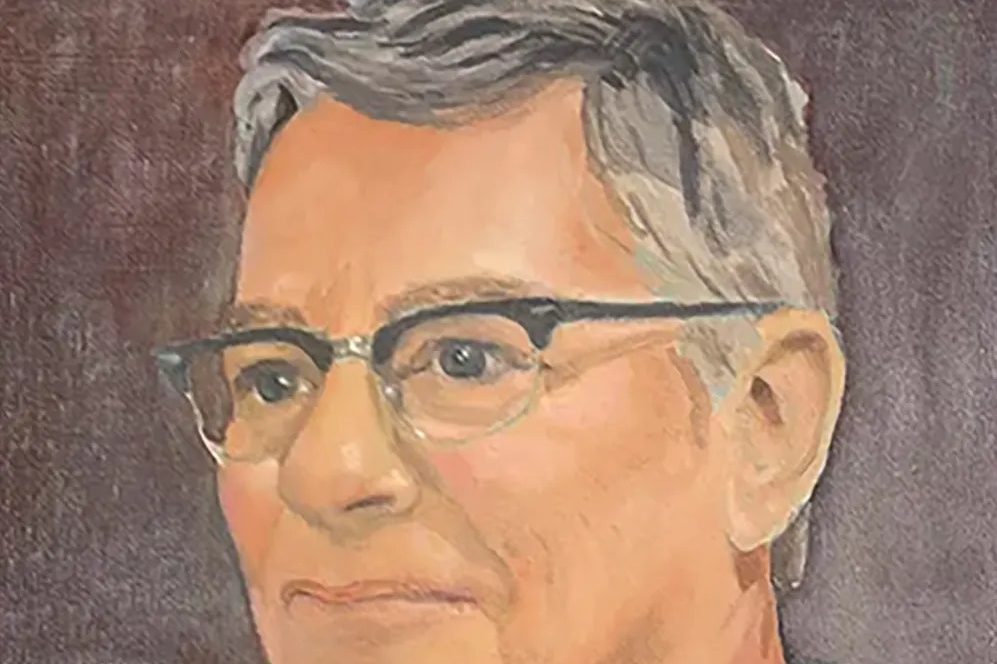

For years I tried to get a small memoir club going down here in Provence; winters can be cold, dark and lonely. I was hoping to encourage Jeremy to write, if not the next literary comic novel — he gave up on that seven years or so before he died — then a memoir at least. But he was writing 800 words a week and having failed to write a memoir in his youth after spending a third of the publisher’s advance, he was loath to try again.

Not long after he died in May 2023 I asked a few friends — Monica and André, the foreign correspondent, his wife Mel and a neighbor, Geoffrey — if they’d be interested in starting a memoir club. The first meeting was on February 9, 2024 — what would’ve been Jeremy’s sixty-seventh birthday. The aim of our club would be to honor Jeremy, with each of us writing and reading aloud a memoir of 800 to 1,000 words. It was a success and everyone was keen to keep it going. This year we welcomed three new members: Jeremy’s old friends Dave Goodhart and Damien McCrystal, and Dave’s girlfriend Kate.

At our second annual meeting Mel kicked off the evening with an account of filming a documentary in the industrial Russian Arctic with a mini-skirted, nightclub-seeking director. Monica’s lovely evocation of a life told through bicycles began with her and her sisters throwing battered bikes into a hedge as the train to school approached, and ended in Provence with André and Jeremy visiting nearby villages on their matching Peugeot racing bikes.

Kate’s vivid childhood almost-drowning adventure with her brother in a dinghy off the beach at Rhossili Bay in the summer of 1973 had us sitting up straight glugging rather than sipping — even though her presence assured us of a good outcome.

Damien reminded us that the 1980s were fun; another universe, where people had real sex

Then there was the textbook far-left activism of “middle-upper-middle class” old Etonian Dave Goodhart’s youth. Rebel Dave “got drunk, dropped acid and his Hs” before “painting a giant hammer and sickle, and the words ‘power to the people’” underneath a high-rise which, when some of the residents complained, he then had to paint over.

Following tartiflette and lots more wine we were taken back to 1957 and twelve-year-old André’s charming and audacious friend, thirteen-year-old Annie, with her garlicky French kisses and exploring hands which revealed to him an exciting but confusing world far beyond his beloved Dinky car collection.

Geoffrey introduced us to Lucifer the orphaned baby sanglier (wild boar) raised by a setter bitch belonging to a French hunter and trapper friend, George. Young Lucifer burnt his little snout in the fire and, as he got bigger, liked to sit on George’s lap, trotters on steering wheel, when they drove into the village. Lucifer’s life ended with a bullet to the head five years later when, through ill temper and bad luck rather than malice, he gored George badly in the thigh with his tusk, narrowly missing the femoral artery. His skull was pinned above the fireplace where he’d burnt his snout and stayed there until George died decades later.

Damien reminded us that the 1980s were fun; another universe, where people had real sex, sometimes with people they shouldn’t have. When he was twenty-five he bumped into an ex-girlfriend’s forty-nine-year-old mother, a former model, who asked him back to her flat. The affair was “predictably short-lived.” A few weeks later the ex-girlfriend suggested a meeting. Over dinner in a small busy restaurant she brought the place to a standstill by shouting: “Why? WHY DID YOU FUCK MY MOTHER?” Forks and glasses dangled midway between tables and mouths, waiters froze, all faces turned. “Because I love you!” The fact that the evening ended passionately in his ex-girlfriend’s place almost made me sorry that the excesses of the 1980s largely passed me by. I was too young, too provincial, too poor, too hardworking and too much in love.

The foreign correspondent brought things to a bloody end in a war zone: Grozny 1994. I was glad I’d had a drink. His colleague, a young photojournalist, had been killed by a Russian vacuum bomb. “Her head lay covered in a shawl on the back seat of the car and her body, wrapped in a blanket, was strapped to the roof.” There was no other way to get her out.

Leave a Reply