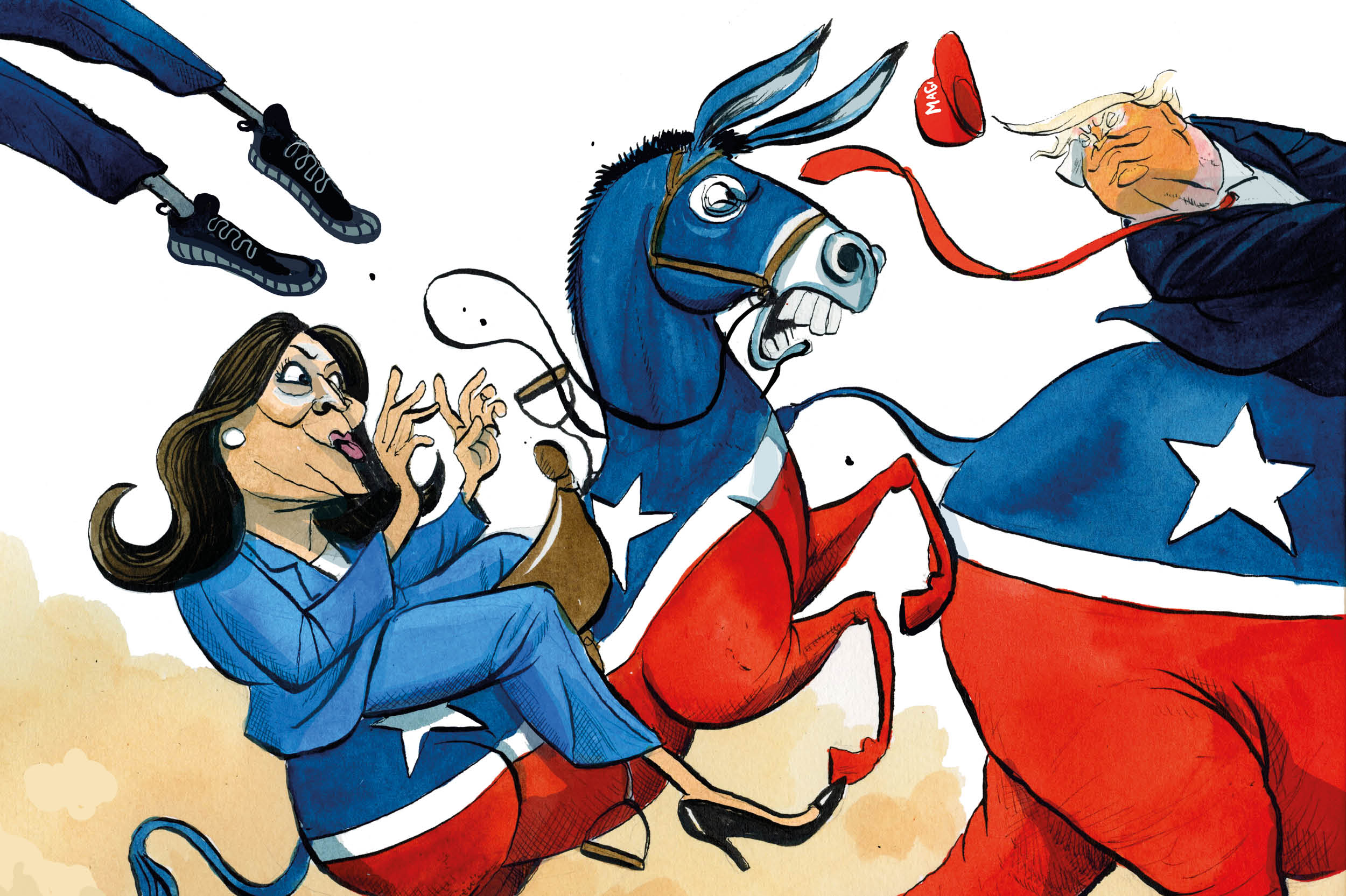

Donald Trump was making modern political history even before he fell ill in the final stretch of his election campaign. By suggesting the result could be fraudulent — and therefore invalid — the incumbent President was menacing the fragile framework that, for more than 200 years, has eased the transition from one administration to another.

There has been nothing like it in living memory, other than Trump’s previous allegations of voter fraud after his 2016 win. But the United States certainly does have a history of dodgy politics — electoral fraud was as American as apple pie throughout the 19th and into the early 20th century. Since then it has been, mercifully, much less corrupt than it was before the 1920s. Ballot stuffing, repeat voting, Election Day violence and the intimidation of entire populations were all familiar tactics in the bad old days, especially when racial issues were in dispute.

Take the election of 1876. The outgoing Republican president, Ulysses S. Grant, was surrounded by dirty politicians and bribe-takers. White Southerners had been bristling with resentment for a decade over the fact that their ex-slaves, freed in 1865, were allowed to vote while some among them had even become politicians. Federal army garrisons stationed in the South protected these racially mixed arrangements against white terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

The Republican presidential candidate of 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes, a Union hero of the Civil War, was the governor of Ohio. His Democratic rival Samuel Tilden had been a pro-Union Democrat in the 1860s and was now governor of New York. Both candidates, ironically, had a reputation for honesty and for favoring good-government reforms. Nevertheless, they got drawn into what has been remembered ever since as the Corrupt Bargain of ’77.

The Electoral College declared, soon after Election Day, that Tilden was just one vote short of the 185 he needed for victory, while Hayes had only 165. Tilden also had a clear majority of the popular vote. However, in three Southern states — Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana — both parties claimed victory and both asserted their right to the crucial 20 Electoral College votes that had not yet been included in the totals.

A commission made up of congressmen, senators, and Supreme Court justices tried to break the deadlock. It had one more Republican member than Democrat, which enabled it (voting on straight party lines) to give all the contested votes to Hayes, making him the winner by just one: 185 to 184. Not until March 1, 1877 was the result finally announced, five months after Election Day.

Behind the scenes, Republican fixers were looking for a way to sweeten the pill for the thwarted Democrats. Their solution was to promise an end to the era of Reconstruction, the political movement that had struggled to transform race relations in the South over the foregoing years. In exchange for getting their candidate into the White House, the Republicans promised to withdraw all remaining troops from the South. Hayes was sworn in on March 4 and within a month had ordered the military evacuation of the South.

The white Southern Democrats might have lost the top job but they reasserted themselves at home, restoring white-only rule, intimidating black voters and legislating in favor of racial segregation. They called themselves ‘the Redeemers’ and claimed to be rescuing their states from barbarism, while actually creating a society based on exclusion, intimidation and lynching. For a few years, black lives had mattered, but now they were sacrificed to the needs of party politics. Not until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, nearly a century later, did it become possible once more for African Americans to vote and to run for electoral office in the South.

President Hayes enjoyed only a single term as president, during which running water and the first telephone were installed in the White House. His wife, Lucy, was a teetotaler, and the couple served no alcohol at official functions. One disappointed visitor to a presidential reception wrote later: ‘The water flowed like champagne.’

Tilden consoled himself with the thought that he had won the voters’ endorsement and yet was spared the hard work of the presidency itself.

A group of northern Democrats, still sore at being cheated, created the ‘Potter committee’, named for its chairman Clarkson Nott Potter, to investigate election corruption in 1876. Telegrams were to the 1870s what emails are to the 2020s and the committee read hundreds of them, sent by party operatives during the 1876 campaign, usually in code. Unfortunately, the decoded telegrams disclosed widespread bribery of election officials — mostly by the Democrats — making it difficult for them to claim that they occupied the moral high ground.

[special_offer]

Elections in the 1870s were very different from those of today. The turnout in 1876 was a whopping 80 percent and it was preceded by months of illuminated parades, big public dinners, and speeches that often lasted well over an hour. Candidates had to speak with enough power, unaided by microphones, that audiences in their thousands could hear them.

When it was time to vote, the ritual was as public as the campaigning that led up to it. Voters who identified with a particular party would step forward clutching brightly-colored tickets, which signaled their allegiance, and place them in the ballot box in front of hundreds of onlookers. In those days, men who had bribed voters could be certain that they were getting value for money. Not until the 1890s would the secret ballot come along, dismaying many of those who witnessed earlier elections. The drama diminished, as did the scope for flagrant forms of abuse.

Democratic government depends on an honest count of the votes. Losers must yield gracefully, while winners have to pledge that they too will observe the rules when their terms end. Fraudulent elections, by contrast, menace the nation itself and, as the events of 1876 show, they can have odious consequences that persist decades into the future.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.