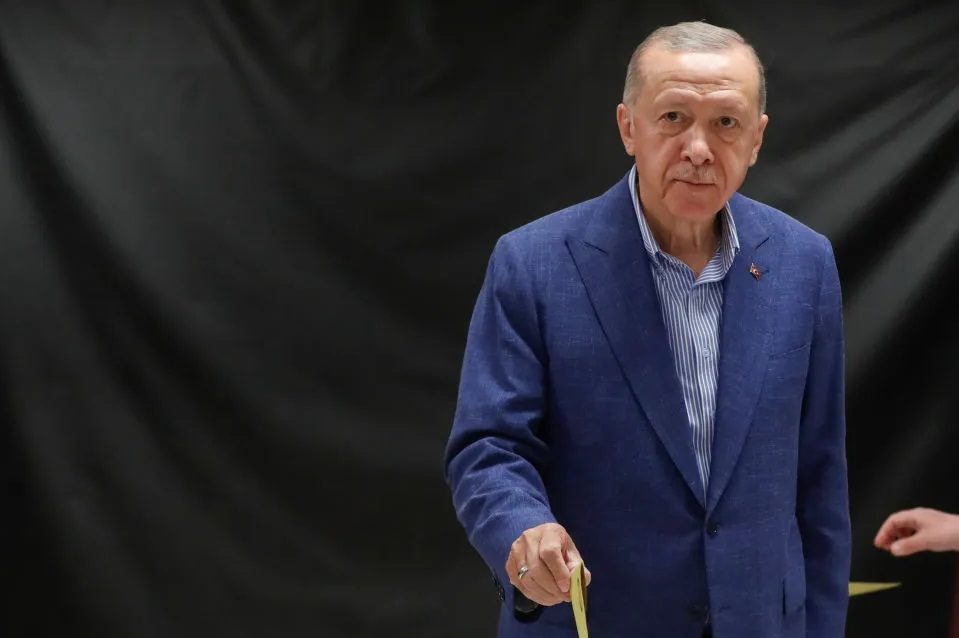

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan seems determined to reinvent the secular Muslim country he inherited as a sort of Sunni Iranian ‘Mini-Me’: draconian, Islamist and with vaunting regional ambitions.

For Western powers and their allies, the urgent question is how to deal with the mutation of a Nato ally into a ‘neo-Ottoman’ threat.

A hundred years ago, the Turkish Republic was founded on secularism. Ataturk banned religion from the public realm, prohibited the Arabic call to prayer, and encouraged men and women to mix.

But for years, Erdoğan has done all he can to reverse the Turkish liberal consensus in favor of a new authoritarianism — and is taking on muscular adventurism abroad.

For Israel and the US, Iran is unlikely to be knocked from the top of their worry list. Other countries in the region, however, are less concerned about a Tehran already weakened by sanctions, COVID and an Israeli air campaign in Syria. It is now Ankara that is keeping them up at night.

Stand beside me on the roof of Erdoğan’s $613 million, 1,100-room White Palace. Whichever way we look, the Turkish juggernaut has changed the facts on the ground.

Over the snowy peaks of the Taurus mountains, Erdoğan now controls 5,500 miles of northern Syria, where he has steamrollered all opposition and is striking deals with Moscow to redraw the border at lightning speed.

Across the Mediterranean, Turkish muscle enabled the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord to crush the rebel Khalifa Haftar in Libya, allowing Turkey to gain a foothold in North Africa and lock out antagonists like Egypt and the UAE.

And beyond the Aras river on Turkey’s eastern flank, Erdoğan is sitting pretty, with the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh ending decisively in favor of his ally, Azerbaijan — with the help of Ankara’s fearsome drone program.

In a sign of the times, Pakistan, traditionally an ally of Saudi Arabia, came down on the side of Turkey in the South Caucasus fight. Islamabad laid money on the right horse.

Western powers have reason to be worried about the rise of the neo-Ottoman empire. Not only does Turkey control Europe’s gas supply and migrant flows, its regional meddling profoundly undermines Western interests.

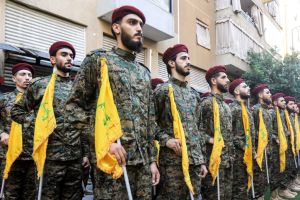

The backdrop to all this is Turkey’s alliance with Qatar. Bonded by their support for Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood, the two Sunni states are formidable supporters of terror. Senior Hamas operatives are welcomed in both countries, and both also reportedly host Hamas’ command-and-control facilities.

Defense cooperation between Turkey and Qatar now runs deep. They jointly provide cyber security to the oil-rich Sheikdom, and the Turkish armored vehicles manufacturer BMC is half-owned by a Qatari investment fund.

Over the years, the two countries — both technically allies of the US — have audaciously worked together to evade potential American and Saudi sanctions, which could have punished their support for Russia, Iran and terror groups.

If the love affair between Ankara and Doha could be symbolized in one object, it would be a $400 million Boeing 747-8, the world’s most expensive private jet, which the emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim Al Thani (who owns a $90 million Ottoman mansion by the Bosphorus) presented as an offering to Erdoğan two years ago.

The neo-Ottomanism doesn’t stop there. Mirroring Iran’s multi-layered drive for regional dominance, Erdoğan has set himself up as the populist figurehead of the Arab world, with the rabble-rousing rhetoric to match.

The Turkish strongman wasted no time in threatening to cut ties with the ‘hypocritical’ UAE after it made peace with Israel. And when Emmanuel Macron spoke out about Islamism in France, Erdoğan declared he needed ‘mental health treatment’. Both speeches went down well with large swathes of the Arab population.

Some analysts suspect that Turkey is over-stretched. But its string of recent victories in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh suggests otherwise.

Its military power is given a boost by Turkish soft power. Its films, television and fiction have long been winning hearts and minds across the Muslim world. Other regional actors are not complacent. While Western powers sit on their hands amid years of American retrenchment, an Arab fightback against Turkish dominance is underway.

The UAE, emboldened by its peace deal with Israel and the resulting influence in Washington, is acting on Saudi, Omani, Egyptian, Greek and French interests to take on Erdoğan. Its main focus is Syria. The Emiratis are trying to bolster Assad and his allies to create a counterweight to the Turks in the north.

The UAE has launched a diplomatic charm offensive in Syria since its Damascus embassy was reopened in 2018, aligning itself with Assad, who is equally concerned about the Turkish threat.

For the moment, this is a campaign of soft power. The UAE has funneled everything from cancer machines to military training to Damascus, as well as offering back-room diplomatic brokering with its allies.

According to some reports, in April, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed Bin Zayed, offered the Syrian government $3 billion to fight Turkish-backed forces in Idlib. True or not, the story captured the flavor of the relationship: the UAE is trying to use the influence it has built to drum up a stiffer resistance to the Turks.

Given the country’s links to the other Gulf powers, Israel and the United States, it is seen as part of a power bloc. In particular, it is acting for the Saudis, who may soon emerge from the shadows to follow suit.

But there are limits on what can be achieved. Principally, the 2019 Caesar Act — American sanctions targeting Syria — prevents private companies from investing in the country, restricting support to a governmental level. The Emiratis hope that their offer to purchase drones and warplanes from the COVID-ravaged US may earn them a sanctions waiver, boosting their bandwidth in Syria.

Where does all this leave the West? Largely, that depends on Joe Biden. Trump’s withdrawal from the region allowed a complex power balance to develop that would be dramatically altered by American reentry.

But Biden remains focused on Iran. Indeed, his stance on this could be a game-changer: if the nuclear deal came back and sanctions were lifted, the wealth that would pour into the hands of the despotic regime would reshape the region and strike fear into the hearts of the Israeli-Gulf alliance.

[special_offer]

Turkey is not going away, however. Erdoğan presents an urgent problem. It is — or should be — intolerable to have a Nato ally acting like an enemy. Yet Western powers are looking the other way.

With Europe hamstrung by disunity, lack of strategy and stultifying bureaucracy, and a United States withdrawn and in flux, it is left to regional powers to act in Western interests.

Sooner or later, the threat must be addressed. The West must find its lost leadership and stand up to the bully of Ankara.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.