Several weeks ago, just in advance of Donald Trump’s second presidency, there was a mass withdrawal of US financial institutions from Mark Carney’s Net Zero Banking Alliance – which committed members to adopt policies of reducing lending to fossil fuel companies and to take other measures aimed at reducing carbon emissions. Are UK banks now preparing the ground to do the same? The senior executives of Barclays and NatWest have decided that they would rather that their annual bonuses were not based on climate targets. Both have removed sustainability metrics from the formulas used to determine the size of their bonuses.

Although both banks will still use climate targets in some capacity in long-term incentive schemes, and will remain members of the Net Zero Banking Alliance for now, it marks a reversal in a process which until recently seemed to be leading inexorably in one direction. It is perhaps also born of a realisation that US banks could well end up with the fossil industry all to themselves. There are now just three US banks listed among the 140 members of the alliance – and all are niche institutions such as the Climate First bank. By contrast, 81 members are based in Europe. Europe hasn’t given up consuming oil and gas – that will be many decades away, if it ever happens – but it is gradually opting out of the business of extracting from the ground. From now on, the profits from that business will increasingly be offshored – unless, perhaps, European banks, too, start retreating from net zero policies. While Carney likes to talk about risk from ‘stranded assets’ – fossil fuels which end up being left in the ground as the world moves towards renewable energy – the real stranding going on is banks isolating themselves from taking advantage of a resurgence in oil and gas production.

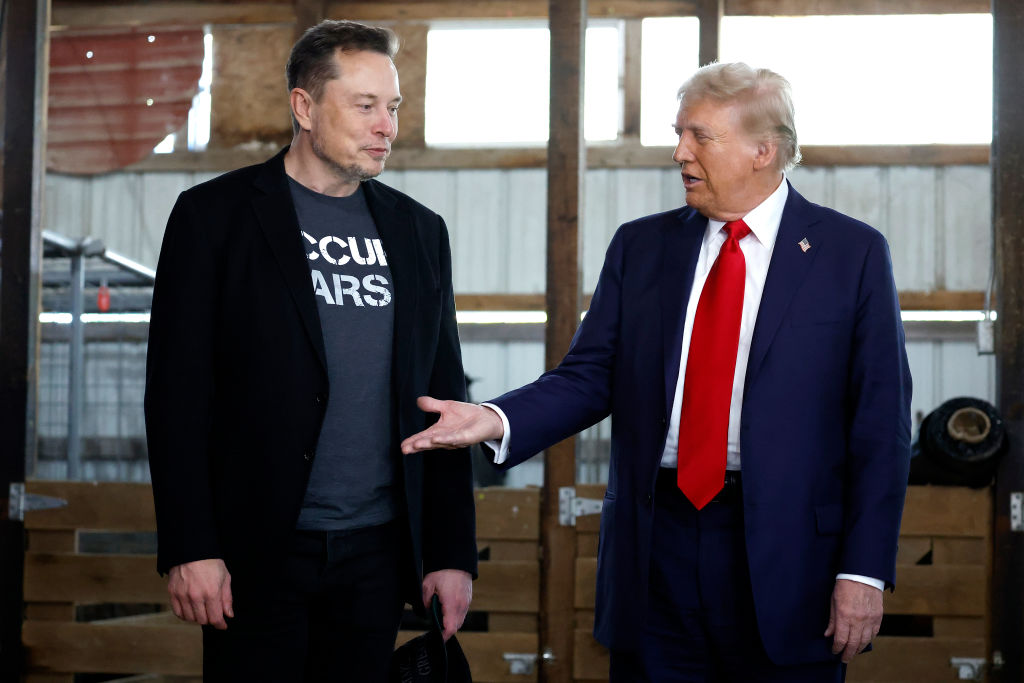

Trump’s promise to ‘drill, baby drill’ has put banks’ sustainability policies in a bit of a quandary. It is no longer possible to pretend – as Ed Miliband likes to make out – that there is no conflict between targets which aim to reduce carbon emissions and the seeking of financial rewards. There are good profits to be made in the short and medium term at least from extracting and refining oil and gas.

But then UK banks have never quite committed themselves to divesting from fossil fuels. Barclays, for example, may be a member of the Net Zero Bank Alliance, yet the only restrictions it has put on lending is for the business of thermal coal (i.e. burning coal to generate heat and power), Arctic oil and oil sands. It has never withdrawn from funding oil and gas extraction, fracking included. Rather it bases its sustainability credentials on £1 trillion worth of finance it intends to advance between 2023 and 2030 for green energy, including hydrogen, carbon capture and batteries. As for its decision to carry on financing fracking it explains: ‘Reserves with shorter lead times remain an important part of near-term energy supply in the International Energy Agency’s NZE strategy. Shale projects, from fracking, typically have a short production cycle, so they can start production within months of an investment decision.’ In other words: we back fracking because it is quick and cheap, and therefore individual shale projects will be over and done with long before their assets get stranded. Much to the chagrin of the fossil fuel divestment movement, UK banks have never been much on their side – even if they like to make the right noises. They may be even less onside in the future.

Leave a Reply