As the latest special counsel files new charges against former president Donald Trump, it’s beginning to look like legal crusades in America are more important than political ones. Locking up one’s political opponents is the sort of thing they used to do in Ukraine, after all, or the totalitarian state of which Arthur Koestler wrote in Darkness at Noon. Just a few years after claims of Russian collusion with the winning candidate of America’s 2016 presidential election were debunked, it is ironic that a Russian’s critique of our political culture nearly half a century ago captures our current predicament so clearly.

Addressing Harvard’s graduating class in 1978, Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn warned: “I have spent all my life under a communist regime and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed,” quickly adding “But a society with no other scale but the legal one is also less than worthy of man.” America’s excessive legalism, the ingrate continued, would eventually be our undoing. “Whenever the tissue of life is woven of legalistic relationships, this creates an atmosphere of spiritual mediocrity that paralyzes man’s noblest impulses.”

In mid-July 2016, I spent the wee hours of one sleepless morning in St. Petersburg on my laptop in an otherwise silent hotel lobby watching retired Lieutenant General Michael Flynn’s speech to the Republican National Convention in Cleveland get drowned out by chants of “Lock her up!” There I was, in the former capital of what Russian president Vladimir Putin once proudly called a “dictatorship of law,” yet now it was my compatriots who were demanding a politician be imprisoned.

After Trump won, the shoe was on the other foot and the chant — from that moment to the present — became “Lock him up!”

During the febrile peak of Russiagate, now two special counsels ago, I was the one facing a chance of getting locked up. My crime was a fairly arcane one: I failed to register as a foreign agent when my work for a Ukrainian politician triggered that requirement. According to the Foreign Agent Registration Act of 1938 (FARA, passed to root out Nazi propagandists operating covertly in the US), when you represent the interests of a foreign government or political figure, you must declare it.

Imagine, for instance, your father were vice president of the United States just put in charge of Ukraine policy when an exiled Ukrainian oligarch hires you to advise his gas company. Would you have to register? What if he were a secretive Chinese billionaire who was later disappeared when news of your arrangement surfaced, or the wife of a notoriously corrupt ex-Moscow mayor? As the recent unraveling of Hunter Biden’s plea deal suggests, how one interprets or applies FARA is, well, fungible.

My own Ukrainian client had a longstanding relationship with Paul Manafort, until, that is, the storied Republican operative landed a big piece of domestic work, which created an opening for me in Kyiv. I’d been working as an international political consultant since helping midwife Iraq’s first free election in half a century in 2005. Mana- fort’s Russian-Ukrainian sidekick, Konstantin Kilimnik, had been my deputy in Moscow when I was promoting democracy abroad and ran the International Republican Institute (IRI) office in Russia during the early Putin years.

If the Russians really engineered the election of Donald Trump — as many were suggesting in all seriousness from the summer of 2016 until Robert Mueller testified before Congress in summer 2019 — someone must have helped them, right? If you were casting “likely suspects” for a B-movie, then, I suppose, Paul, Konstantin and I just about fit the bill — but you’d still have to be squinting.

This is where my exposure to the American criminal justice system began. From the time the FBI arrived on my doorstep, it took about six months to plead guilty, and a little over a year to be sentenced (many, arguably most, wait much longer). That plea cost me a quarter of a million dollars. Had I gone to trial, I would have sunk millions of dollars into debt for the privilege of facing a DC jury while prosecutors reminded them that I was a Republican.

As I explain in my forthcoming memoir, Dangerous Company: The Misadventures of a “Foreign Agent,” surrender and cooperation were the logical choice, especially as I didn’t have much to hide.

“First of all, this has nothing to do with the president,” then-Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani told the Washington Post when they for some odd reason contacted him about my arraignment, “and secondly, the next thing you know, Bob Mueller is going to be handing out parking tickets in Russia.”

Giuliani’s off-hand remark cut to the core: was Russiagate the investigation of an actual crime, or was it an investigation in search of a crime?

Regardless, because the political outcome of Trump’s victory was so riven with discord, a legal approach had become necessary. Sixteen years earlier, it took the US Supreme Court to validate George W. Bush’s victory, and forty years before that, a case originating in the US District Court for the District of Columbia (where I was convicted) led to the downfall of the Nixon administration. The legal review of political issues is nothing new in America.

But we’ve recently seen much evidence of the legal system being abused to paper over political disputes and weaponize the administration of justice.

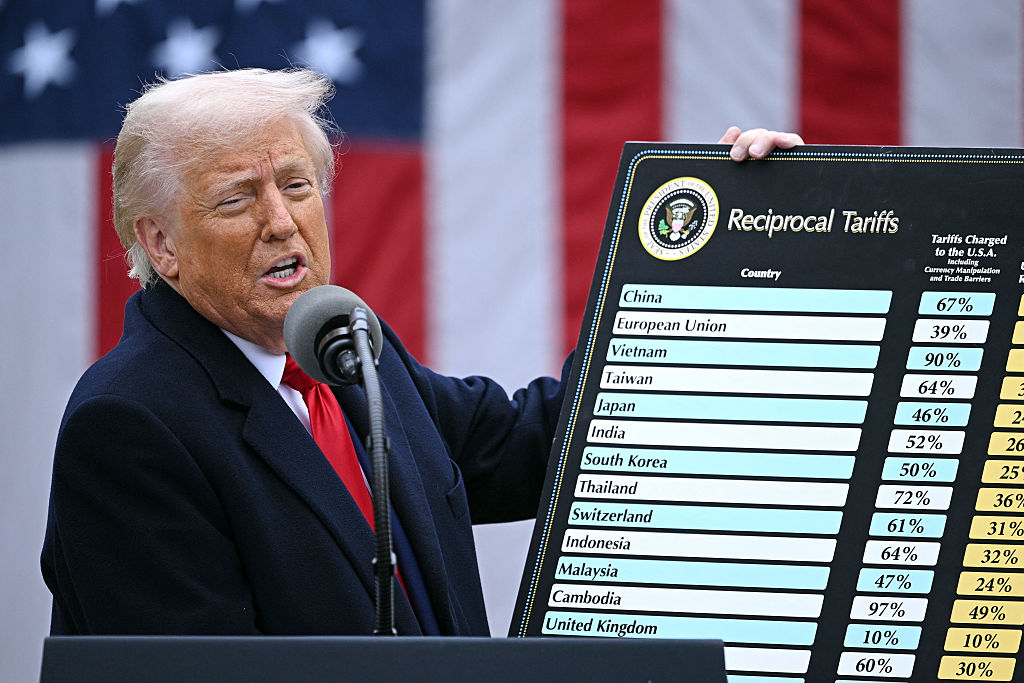

Politically speaking, the problem with the New York case against Donald Trump, involving hush money to a porn star violating FEC rules, as well as the Mar-a-Lago classified documents-handling case, filed in state and federal jurisdictions respectively, is that, in both instances, the other side is far from innocent. Hillary for America did not disclose the money it spent generating and ginning up the Russiagate probe with the “Steele dossier”; the FEC fined her campaign and the DNC about $100,000, case closed. The current president had plenty of classified documents scattered willy-nilly around his various properties — even if he was more cooperative when asked to return them. So why do we have a nuclear-level prosecution of one side and a kid-glove treatment of the other?

The only way to accept glaring contradictions like these is by practicing the same defense as those who lived under the Soviet regime: cognitive dissonance. When I was pleading guilty, a Russian friend counseled me: “just pretend it isn’t happening to you.” That is what Soviet citizens had to do every day in order to psychologically survive under a government they knew lied to them morning, noon and night.

As Americans we’ve adopted our own cognitive dissonance that allows Democrats to look past the troubling symbol Hunter Biden represents, and Republicans to dismiss Trump’s vulgarity.

Yet this separation, this bifurcation, this split is inherently unstable. In warning us about it, Solzhenitsyn evoked the line from Lincoln — “a house divided against itself cannot stand” — in titling his Harvard speech “A world split apart.” He had escaped a very different world — the gulag and repressive state — and having found sanctuary in the woods of Vermont, discovered he could not be silent about the trends he observed in this new land.

He explained that in the old land, to which he returned after the fall of the Soviet regime in 1991, “there is a multitude of prisoners in our camps who are termed criminals, but most of them never committed any crime; they merely tried to defend themselves against a lawless state by resorting to means outside the legal framework.”

“The more corrupt the society, the more numerous the laws,” the Roman historian Tacitus lamented of his own time. Americans today must lawyer up to protect ourselves from the state — or I did anyway. When we elect prosecutors such as Adam Schiff, Democrat of Hollywood, to Congress, we should expect we’re going to get courtroom-style theater in lieu of governance. Though she did end up with the Number Two job anyway, Kamala Harris’s pledge to be America’s “prosecutor president” gained her little traction in 2020.

Had he lived until 2014, Solzhenitsyn would have loved Andrey Zvyagintsev’s powerful film Leviathan, in which an ordinary Russian citizen is crushed first by the corrupt state and then, even more devastatingly, by an amoral legal establishment. Let it be a cautionary tale for us too. Relying solely on legalism to mete out justice and effect political outcomes will in all likelihood leave us even more disappointed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2023 World edition.