The world has many island nations, and sometimes the United States counts itself among them. We have water on either side of us, and though we share our big island with Canada and Mexico, neither poses any threat. America is immune to invasion, a castle surrounded by the safest of moats.

This wasn’t always so, and it isn’t really true today, unless we forget about Hawaii and our Pacific and Caribbean territories, most of which would be easy prey for other states if they weren’t under our sovereignty. In the earliest days of the republic, we shared the North American continent with outposts of Europe’s leading powers: France, Russia, Spain and Britain. Only the British were committed to staying, and that proved to be what made American ‘isolationism’ possible: supreme upon the seas, the British checked the ambitions of everyone else.

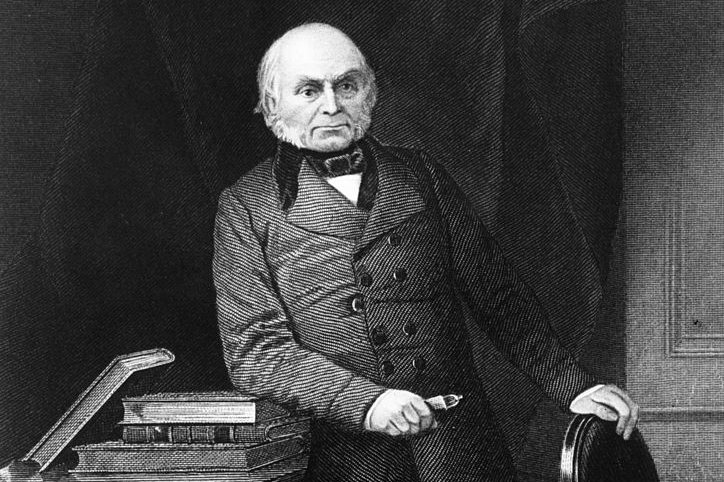

From the Monroe administration onward, Americans were mostly content to leave policing the 19th-century version of the ‘liberal international order’ to the British. When British liberals asked Americans to join a crusade against authoritarian regimes (plentiful after the Napoleonic Wars), Monroe’s secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, replied in his famous July 4, 1821 speech: America ‘goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.’

The chink in America’s isolationist armor was obvious from the start. If Britain should prove incapable of policing the other great powers — as turned out to be the case in both World Wars — we would face the choice of either allowing someone less like ourselves to shape the international order, or becoming its new policeman. The significance of the international order to our regime’s character was evident even before 1914. When Europe was frenziedly engaged in colonial acquisitions, American jingoes modeled themselves on the jingoes across the ocean, just as 100 years earlier many Americans had defined themselves by the politics of the French Revolution. In 1899, Theodore Roosevelt rhapsodized about how, through counterinsurgency warfare and imperial administration in the Philippines, ‘We will play our part well in the great work of uplifting mankind.’

The Bolshevik revolution would likewise inspire a generation (and more) of American communists and fellow travelers. Even fascism enjoyed a vogue among American intellectuals in Mussolini’s 1920s heyday. The success of new regime types in Europe almost always incites fresh domestic challenges to America’s constitutional order. Moats the size of oceans can keep out any army; they cannot keep out ideas. And when ideas are strengthened by apparently successful foreign examples, our ideologues demand regime change at home. The reaction against this fad also colors domestic politics. The American left and right can be simultaneously remade by their responses to big changes in the European order.

All of this might seem like a powerful case for American hegemony, at least in Europe. If we want to maintain our way of life at home, we must ensure that Europe reflects our values. The extraordinary revulsion of American liberals at the moderately illiberal regimes of Hungary and Poland is a symptom of this psychology. Liberals like Michael Bloomberg are happy to do business with an oppressive regime in China. But Orbán in Hungary, or Brexit in the UK, are perceived as a threat to liberalism at home. Russia is just European enough to be the greatest horror of all.

Likewise, Putin and other Russian leaders fully understand what the American model, and American-sponsored models in Europe and on the borders of the motherland itself, mean for the regime in Moscow. The assimilation of Ukraine to the western sphere, however haltingly, registers as a near-existential threat. If Ukraine can become liberal and democratic in something like the West’s image, the influence of that image in Russia will only grow. As will the backlash.

Yet the dream of a more perfect liberal order is a mirage. Its pursuit threatens to sacrifice the security that America and western Europe can actually sustain. British liberalism, with all its humanitarian values and theories of free trade, could not prevail in the contest with German power. Luckily for the British, a less than fully liberal America, with an industrial organization that was more than a match for Germany (and Japan), was prepared to come to the policeman’s rescue.

There is no rescuer standing by for the United States today. If we lose to our ‘Germany’ — China — the world order will shift more dramatically than it has at any time since the 15th century. China does not inspire open imitation to the degree that the European regimes of the 19th and 20th centuries did, but its example blunts the appeal of American and western prestige. Why should Turkey or India follow western models when China produces better results?

Faced with such a competitor in the economic and ‘regime stability’ sweepstakes, America, and Europe’s, only hope lies in strengthening their own economic positions and demonstrating not that western values can take root in Kabul or Moscow, but that they are not yet uprooted in Chicago or Bremen. The attempt to expand liberalism at the periphery while the West rots at its core is nothing short of suicidal.

American hegemony in the service of a liberal world order no longer protects our civilization: it reinforces our most economically and culturally self-destructive tendencies. For it is not the West that depends on liberalism, but liberalism that depends on the West. America is no island, and America First was the wrong policy for 1941. Today, if America and Europe do not put themselves first by exercising restraint in foreign commitments and emphasizing domestic order, they will not be strong enough to inspire anyone else — or even to preserve their own way of life.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2020 US edition.