Does Joe Biden think that Putin is a killer? asked ABC host George Stephanopoulos. ‘Mmm-hmm, I do,’ answered the President. Once, that would have been fighting talk. Today? Biden can insult Putin with impunity because he believes that Russia is, quite simply, no longer important or dangerous. Once a deadly serious enemy whose rivalry threatened to destroy life on the planet, Russia’s diminished status means that, these days, there’s little left to the grand old conflict except mere mudslinging.

‘We no longer think in Cold War terms, for several reasons. One, no one is our equal. No one is close,’ Biden told Ukrainian lawmakers in Kyiv in 2014. ‘Other than being crazy enough to press a button, there is nothing that Putin can do militarily to fundamentally alter American interests.’

Russia and the United States are like an old divorced couple, still bickering 40 years after their stormy superpower marriage broke up. Russia is still dependent on her ex’s power and glamour to prove her continued status in the world. And many Americans still secretly love to have a reliable foreign baddie to blame when their democracy wobbles. The old thrill may be long gone, but both former partners still manage to kick up a few sparks from the old Cold War ashes. America’s insistence that Russia is interfering with her democracy and that her spies are everywhere gives Putin a wonderful domestic boost to his status as international evil genius and all-powerful spymaster. Arch-Russiagaters in the US get to write off Donald Trump’s election as a Kremlin plot rather than try to understand it as a popular revolt against the Washington establishment.

Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin have been taking potshots at each other for at least a decade. The last time Joe visited Vladimir in the Kremlin was back in 2011, when Biden was VP and Prime Minister Putin his counterpart, having temporarily swapped positions with Dmitry Medvedev. ‘I’m looking into your eyes, and I don’t think you have a soul,’ the vice president said. Putin smiled and replied, ‘We understand one another.’ At least that’s what happened if you believe Joe Biden. Maybe Biden does understand Putin, though. George W. Bush found Putin ‘very straightforward and trustworthy’ after looking into his eyes and getting ‘a sense of his soul’. Donald Trump called him ‘extremely strong and powerful’. Biden has no such illusions.

Whether Putin understands Biden is less clear. Putin’s response to the ‘killer’ charge was effectively to call Biden a killer himself. ‘When I was a kid, when we were arguing with each other in the playground, we used to say, “What you say is what you are,”’ said Putin. He also wished Biden ‘the best of health’. Given that Biden had just publicly accused Putin of being a poisoner, this came across as the slightly sinister ‘mind your step’ valediction of a mafia boss. There must have been laughter in the Kremlin the next day when Biden slipped not once but thrice clambering up the stairs to Air Force One. Yes, Putin commands the only nuclear arsenal in the world that can match America’s. But in every other sense Russia remains, as Henry Kissinger put it, ‘Upper Volta with nuclear missiles’. Russia’s economy is nominally the 11th largest in the world, between South Korea’s and Brazil’s. Per capita, it’s 61st, in the neighborhood of Bulgaria and Grenada. The US’s $700 billion defense budget alone would account for half of Russia’s GDP.

Unlike the USSR, Putin’s Russia has no regional or international allies to speak of, and wields little ideological soft power. The only ways the Kremlin has managed to throw its weight around since the collapse of the Soviet Union have been by invading much weaker neighbors like Georgia and Ukraine; deploying its military in places the west has declined to get involved in, like Syria and the Central African Republic; and engaging in illegal (the diplomatic term is ‘asymmetric’) warfare fought by hackers, trolls and poisoners.

So when Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, insisted on March 30 that ‘neither Putin, nor anyone else from the Russian administration, will allow the US or other nations to talk to us from a position of power’, his words must have rung a little hol- low in the White House.

Nothing hurts more than contempt. Putin is famously touchy not only about his own personal stature but about Russia’s. Above all, Putin wishes to be seen as a peer of Biden, Xi Jinping and Angela Merkel. He loves to keep other leaders waiting (Merkel holds the record with four and a half hours; Queen Elizabeth II got off lightly with just 14 minutes). That power game reached its absurd culmination in 2018 in Helsinki, when Trump and Putin waited each other out for 50 minutes, neither being willing to mount his motorcade before the other was en route.

‘Of course we love Trump,’ one Russian senator told me as we waited in a Moscow TV studio for the leaders to appear.‘He acknowledges our power. It’s just like the old days.’ Sadly for the Kremlin, Trump’s brief revival of superpower-style summit diplomacy provided only a fleeting moment back in the sun of presidential regard. Unlike Trump, Biden has a long record of standing up to Russia. As a member of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations he was a regular visitor to Eastern Europe from the 1970s onward. During his Kremlin meeting in 2011 Biden caused diplomatic waves by questioning whether Putin should return to office as president — and was strongly opposed to Obama’s attempts to ‘reset’ relations with the Kremlin.

Today, Biden’s dislike of Putin is as much personal as ideological. During the 2020 campaign, the CIA reported in January, Putin personally authorized an anti-Biden smear campaign via a pro-Kremlin Ukrainian parliamentary deputy named Andriy Derkach. Intelligence officials in Russia’s FSB produced edited recordings of telephone conversations from 2016 between then-VP Biden and former Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko. The FSB passed the recordings to Derkach, who in turn leaked them to Trump’s associates Rudy Giuliani and Roger Stone. This Kremlin-controlled Ukrainian disinformation network also sent congressional leaders reams of documents with information designed to discredit Biden and his son Hunter, an operation over which, according to the CIA, Putin personally ‘had purview’.

Unsurprisingly, the Democratic campaign launched a vigorous counteroffensive — and Biden himself promised to take ‘decisive measures’ against countries found to be interfering in US elections, a warning he repeated in the Stephanopoulos interview in March. In fact, while the CIA’s report ‘Foreign Threats to the 2020 US Federal Elections’ found evidence of Russian ‘influence’ through propaganda and smears, there was none of actual ’interference’, which the Agency defines as attacks on ‘technical aspects’ of democratic infrastructure such as voter lists and vote-counting procedures.

Nonetheless, Joe’s mad. The Departments of State and Treasury are drawing up new sanctions against the Kremlin, though more as a ritual signal of disapproval than in the expectation that Putin will actually take any notice. Since 2012 the US has imposed dozens of rounds of sanctions as punishment for the Kremlin’s role in killing the whistleblowing lawyer Sergei Magnitsky; invading Crimea; shooting down a civilian airliner; hacking the Democratic National Convention and voting machines; spreading pro-Trump disinformation on social media; and illegally using chemical weapons in the poisoning of defector Sergei Skripal and his daughter. The US has blocked the bank accounts and properties and visas of hundreds of Russian officials, excluded state-owned companies from international financial transactions, and banned Western companies from participating in major Kremlin-backed infrastructure projects.

There’s not the slightest sign that any of these sanctions has changed Putin’s behavior. Indeed in many ways the sanctions have been a godsend to Putin, allowing him to blame Russia’s problems on hostile foreigners and pose as the Motherland’s defender against Yankee aggression. ‘Sanctions have become a sort of modern bearbaiting; they simply boost the anger and defiance of the bear, while offering the satisfaction and public acclamation of inflicting pain,’ argues Sir Anthony Brenton, who was British ambassador to Moscow during Putin’s first term.

Economically, neither side has any real skin in the game — Russia is America’s 30th largest trading partner, coming in just below Chile, with only $24 billion in mutual trade. The US is self-sufficient in energy and, unlike Europe, it has no need of Russia’s gas. Diplomatically, the US’s periodic attempts to make nice in the Kremlin have coincided with efforts to build international coalitions against Tehran or Pyongyang. But Russia has its own interests in keeping both nuke-free; it shares a sea with Iran and a land border with North Korea. Militarily, Biden has reaffirmed America’s commitment to Nato, which has reassured nervous allies like Poland and Estonia who have been worried by saber-rattling Russian military exercises on their borders. On arms control, Biden has another five years of the recently extended New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty left to run, so doing a new deal with Moscow on ICBMs can be kicked into the next presidential term.

In fact, over his 21 years on the throne, Putin has scored only one significant diplomatic and military victory: keeping Bashar al-Assad in power. The deployment of a single squadron of 35 modern Russian warplanes turned the tide of the war against the rebels and made Syria into Russia’s first (and so far only) client state of the post-Cold War era. Other Russian interventions in Africa and Libya — mostly through the deployment of mercenaries from the Wagner Group — haven’t yielded any real strategic advantage. That leaves only three real points of friction between Biden and Putin, none of them crucial. The first is Ukraine, where Russian troops raised tensions in early April by conducting exercises near the border. But even Putin knows that an open attack on Ukraine would trigger a conflict with the US and EU that, even if it fell short of a shooting war, he couldn’t hope to win.

The second is the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline connecting Russia to Germany and Eastern Europe’s gas networks. Washington and Berlin have been arguing over the dangerous economic dependence that this might cause for a decade — but Berlin remains determined to push on regardless, despite US sanctions excluding European firms from the construction and financing.

The third, and most ominous sounding, is the threat of a military alliance between Russia and China. Moscow and Beijing’s ties have warmed as relations with the West have cooled. A 19-year-old Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship is due to be extended and expanded in July. Chinese troops, who have been training alongside Russians since 2018, will this year take part in wargames on Russia’s European border for the first time. But at the same time Beijing has been mercilessly eroding remaining Russian influence in Central Asia. China’s $100 billion-a-year trade with Russia is largely limited to gas and oil imports — and is six times smaller than China’s overall trade with the US. President Xi may find Putin a useful diplomatic prop in his ongoing power games with Washington. But both Biden and Xi know that the only global power relationship that matters is solely between them.

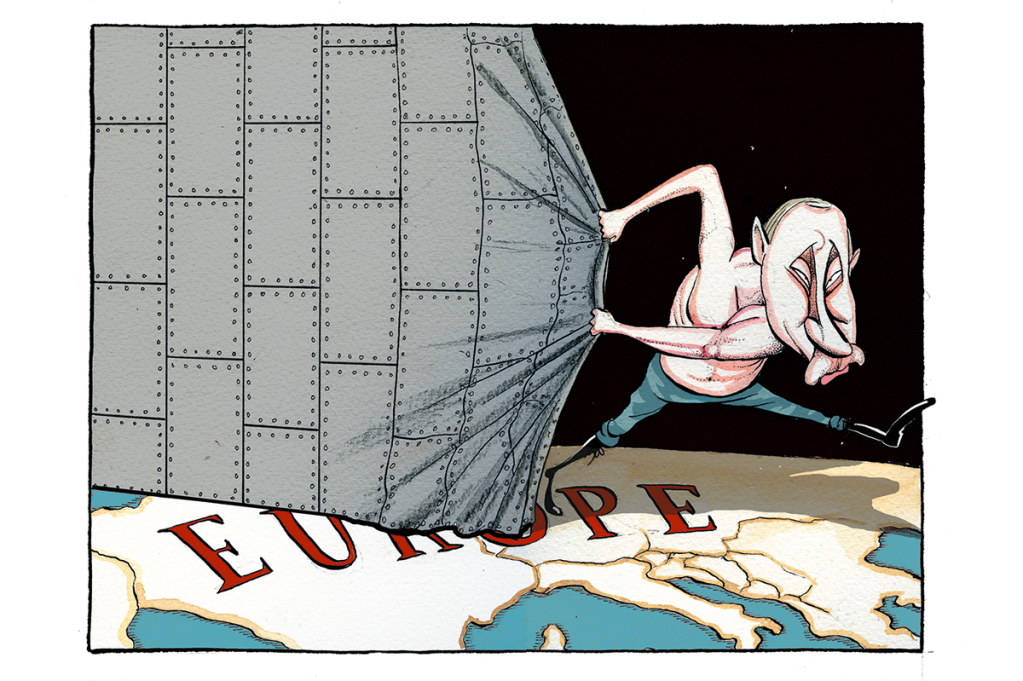

The currency of today’s US-Russia Cold War redux is not the small African war of yore — Upper Volta with or without rockets — but diplomatic démarches, the closure of a consulate here, the recall of an ambassador for ‘consultations’ there. TV footage of diplomats heading to the air- port — Trump expelled 60 Russians in the wake of the Skripal poisonings in 2018 — may be eye-catching, but such gestures are the strategic equivalent of loose change. Cold War symbolism, on the other hand, is still very much in play, especially on the Russian side. The Russian political class and the Kremlin-controlled media remain obsessed with America. The chaos and violence of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US were covered in enormous detail. (Soviet TV, too, used to be big on the imminent-collapse-of-capitalism genre of foreign news). The imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny and the participants in street protests and their leaders are denounced as Western stooges, another leaf from the Soviet-era journalistic playbook. The Duma has brought in strict new laws banning internationally-funded NGOs as ‘foreign agents’. ‘Putin needs the US as an enemy for his own domestic legitimacy,’ says Michael McFaul, who was Obama’s ambassador to Moscow from 2012 to 2014. ‘After annexing Crimea in 2014, Putin gave up on trying to integrate in the West, and now sees himself as the leader of an international, conservative, orthodox movement against the decadent, liberal West.’

That narrative was briefly thrown off kilter by a warming in relations under Trump. Now, with Russia and the US back in their roles as one another’s reliable bugbears, everyone’s back in their comfort zones. Let the bickering carry on.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2021 World edition.