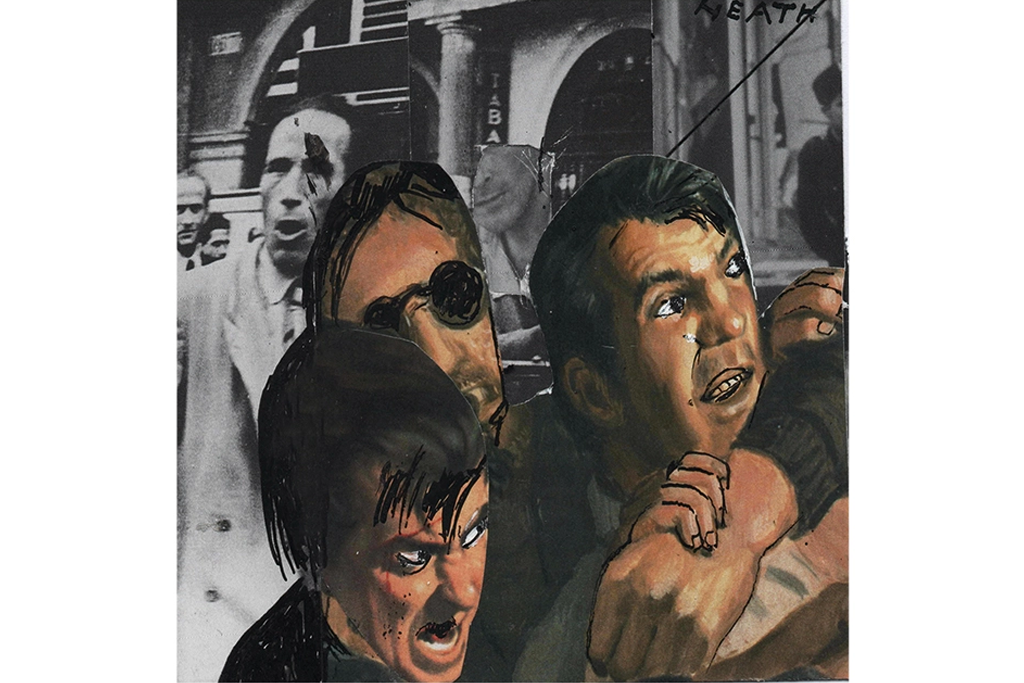

My first taste of proper street violence came in a Transylvanian town square thirty years ago. Ethnic Romanian and Hungarian villagers were going at each other with pitchforks, knives and strips of wood they had ripped from park benches. In an attempt to separate the two sides, the Romanian army had driven half a dozen armored vehicles into the middle of the square. Just as things seemed to calm down, a group of villagers came running out of a hotel, pursued by fired-up Hungarians. As I ran to avoid the melée, a man appeared holding a chunk of wood and hit me over the head. For a second I was stunned. Then my survival instinct kicked in. “I’m English,” I shouted in my best Hungarian. “English!” He stopped mid-swing. His intention had been to crack a Romanian skull, not bruise a British one. But soon his compatriots had gathered around, weapons raised, and they weren’t in the mood to listen. Protest as I might, the noise of the armored vehicles drowned out my shouts of neutrality. Then I had a stroke of luck. A local Hungarian TV journalist, well known to my assailants as that-guy-on-the-telly, recognized me and began clapping and cheering. “Hero!” he shouted. “He’s an English hero.” The mob froze. “Now’s your moment,” the journalist said into my ear. “For God’s sake, don’t run.”

The spell held. A half hour later I watched as the mob caught another man — this one a real Romanian — and beat his head with rods. Eventually the beatings began to sound like a boot stepping into soft mud. The fight, the first violent story I covered as a journalist, took place in a town called Targu Mures. I was one of the few foreigners present and the next morning my account, delivered down a scratchy telephone line, ran at the top of the BBC news.

Looking back to that violent night in 1990, I realize that I was lucky. Three hundred people were injured and six were killed. But Transylvania was also lucky. This northwestern third of Romania, enclosed to the east and south by the sweep of the Carpathian Mountains, has been contested for centuries. Somehow, even as its far more advanced neighbor Yugoslavia began its bloody disintegration, Romania avoided civil war. With a flurry of nationalist flag-waving, bickering and plenty of EU money, the country emerged from its violent post-communist adolescence to become, if not a leading European citizen, then at least a reasonably balanced adult.

This month I spent a few days visiting Cluj, the unofficial capital of Transylvania, and its rural surroundings. My American companion and I arrived on the night train from Budapest and spent three days riding through the hills with a group of Hungarian horsemen. Two were modern-day hussars and had received an EU grant to preserve the traditions and uniforms of their forbears. A third looked more like a cowboy from the American West. We cantered over hills, past shepherds tending their flocks and trotted through villages where Romanians, Hungarians and gypsies still live cheek-by-jowl. For lunch we ate onions, radishes and hard slabs of pig fat on bread.

As we rode along an icy river bed and through a forest one morning, I asked the horsemen how relations were between the different nationalities three decades after they had come so close to civil war. “Most of the tension has gone,” said the twentysomething who breeds his own horses. “But if you are asking me who my friends are, they are all Hungarian. I have Romanians I get on with — they don’t bother me and I don’t bother them — but none I would call a friend.” All said they speak a bit of Romanian but mostly stick to their own. When it comes to political leadership, they look to Budapest rather than Bucharest. “We are all for Viktor Orbán,” the cowboy said over a glass of homemade wine. “I’m not saying he is perfect but he is ours and he helps us.” Several of them cited local Hungarian buildings that have been restored with money from Budapest. “That is an Arpad-era church,” one of the hussars told me with pride, pointing to a building from the time of the founder of modern Hungary, who arrived in the Carpathian basin a thousand years ago.

Cluj was clearly struggling when I lived there in the 1990s. The municipal buses had holes in the floor through which you could watch the road go by. There were miles-long lines for petrol. Even the traffic lights were unpredictable, sometimes turning from red to amber and then settling back to red again. Today the city is bustling. Most high-end western brands have outlets in the two new shopping malls.

Why did Yugoslavia erupt in the early 1990s and Transylvania did not? The ingredients appeared to be there. The nationalist mobs were hot-headed enough and I remember being approached by a Hungarian firebrand politician asking me to help him secure weapons and military training for his people. Part of the reason, no doubt, is that there was no Slobodan Milošević, who drip-fed guns, funding and power to ultra-nationalist Serbian goons willing to pursue his mono-ethnic vision. The math in Transylvania was different too. Cluj was one of the most important Hungarian towns for centuries and when I was living there, about a third of the population was Hungarian. Today, with widespread emigration to Hungary proper and a roaring economy that has sucked in thousands of Romanians from elsewhere in the country, that number has probably fallen to 10 percent. “Conflict is just not an option for us,” a local Hungarian academic told me. “We have to defend our rights and we have to look after our culture, but without creating animosity among the Romanians. If we do that, we can only lose.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.