“Now, what I want is Facts… You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them.” When Dickens begins Hard Times with these words, spoken by the odious, square-faced Mr. Gradgrind, we are left in no doubt that, for Dickens, an education should consist of far more than simply having imperial gallons of facts poured into us until we are full to the brim. The novel’s opening scene is a wink shared between naughty school-children, between Dickens and us, reminding us that teacher is being absurd. Of course knowledge means more than just an accumulation of facts.

But what then? Simon Winchester’s Knowing What We Know is a loose run-through of several millennia’s worth of epistemology and approaches to the transmission of knowledge. It begins with the author’s childhood shock at a wasp sting. This is a powerful kind of experiential learning, more painful but more memorable than Gradgrind’s rote learning. “I had inadvertently acquired a morsel of knowledge,” observes Winchester philosophically, before introducing Plato’s Theaetetus with its theory of justified true belief. We then consider some of the world’s systems of education and examination, the aggregation and storage of knowledge in libraries and encyclopedias, the transmission — and manipulation — of news, and the recent history of machine intelligence, before finishing up with a few of history’s great polymaths: Srinivasa Ramanujan, Benjamin Jowett and Shen Gua.

There is a nicely global focus to Knowing What We Know, enhanced by Winchester’s own experiences as a journalist in Asia. Early on he has a surprising detail about the Boxing Day earthquake of 2004. To recap, this was the third largest earthquake ever recorded, off the coast of Sumatra. The tidal wave that it sent radiating across the Indian Ocean killed nearly a quarter of a million people in Thailand, India, Sri Lanka and beyond. Winchester’s focus is on the Andaman Islands, just a few hundred miles north of the quake’s epicenter. When the tsunami struck the islands’ beaches it was traveling at something like 500 miles per hour. Of the thousands who were killed, almost all were comparatively recent arrivals, settlers — within the last few generations — from the Indian mainland. Of the island’s indigenous inhabitants — the Onge, Jarawa and Sentinelese — none was among the dead.

For them, ancient knowledge about earlier waves was culturally embedded: sudden environmental changes — “the swift out-running of the tide, the unexpected drying of the sand, the changed color of the sea-water” — mean run inland and up into the hills. Exactly how these warnings were passed orally down the generations is not quite clear: likely codified in poetry or song, but definitely not written up in the brute forms of health and safety advice that we western Gradgrinds are used to. What is notable, too, is that it should persist as wisdom, and of existential benefit, in our own era alongside the types of information that have threatened to supplant it.

In 1934, in between “Ash Wednesday” and “The Four Quartets,” when T.S. Eliot was experimenting with theater, he composed a pageant play called The Rock which includes the anguished lines:

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Information, knowledge, wisdom: it is a distinction, an anxiety, that we might recognize as we wade haltingly through a world awash with data. In fact, as Winchester notes, Eliot’s lines may be the origin of what information scientists now call the DIKW pyramid, a qualitative model where data, properly harvested, becomes information, which may produce knowledge, which, in turn, is the foundation of wisdom.

Winchester does not dwell too long on the niceties of these categories, and in fact his book’s structure is curiously resistant to our working our way up the DIKW pyramid. Each of its six chapters is divided into a dozen or so numbered sections which read like standalone pieces. Winchester is clearly at his most comfortable when he’s telling a story rather than building an argument. Here are half a dozen pages on the Encyclopedia Britannica; a paean to the London Library; the plot of Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop; a reminiscence about how Winchester got into Oxford…

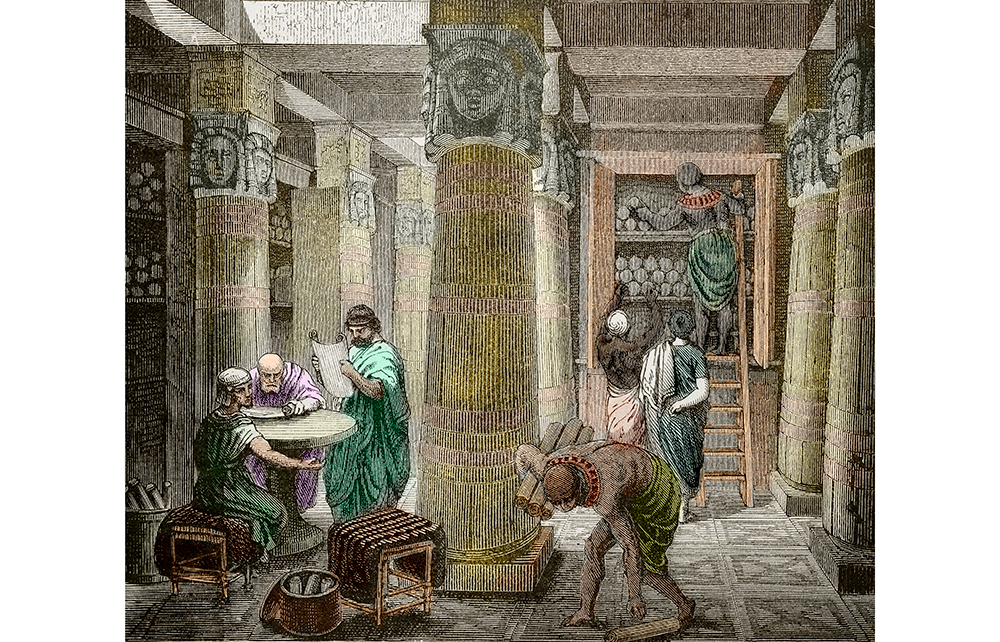

Over the past three or four years there has been a glut of popular books, many of them very good, on the history of information. To name but a few, we have had Judith Flanders on alphabetical order, Simon Garfield on encyclopedias, Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen on building libraries, and Richard Ovenden on burning them down. As a consequence, Knowing What We Know finds itself in a crowded space, with many of its set pieces still fresh from other tellings. Cai Lun and the invention of paper, the library of Alexandria, Gutenberg, Diderot, Oxyrhynchus: all are present and correct.

One might fairly argue that these are essential building blocks, familiar but indispensable to the author’s larger project. Unfortunately, this larger project is hard to discern. Between the dozens of numbered bloglets there is almost no connective tissue. Each tale is interesting and elegantly told, but the synthesis which will turn them all from information into wisdom is left almost entirely to the reader. The oversight is exasperating and really quite surprising. Having read Winchester’s book, I know a little more than I did before, but I am none the wiser.

If that sounds like a harsh verdict, I have some sympathy. It is a difficult time to be writing usefully about knowledge. When my spiral-bound review copy of Knowing What We Know arrived a couple of months ago it included a short section on the AI known as GPT-2. Winchester asked it to rewrite the ending of Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” and the results (free verse: no rhyming or iambic pentameter) were interesting but not mind-blowing. At least not by the standards we have recently become used to. In the past four months, Winchester’s original speculation that “these bugs may be worked out in GPT-3” has come — astonishingly, perhaps ominously — to pass. A week ago, another copy of the book — hardbound, with the finalized text — arrived at my door, so I turned to this section to see if any last-minute additions had been added in the wake of ChatGPT. Sure enough, there is a new paragraph acknowledging GPT-3.5 as “game-changing,” and observing that “it could write truly funny jokes, compose limericks, write dissertations in the style of the Bible or Harry Potter or Socrates.”

This was indeed true, but now we are already on to GPT-4, ten times more powerful still, and attuned to features such as dialogue and emotional register. “No doubt by the time this book is published, even more GPT magic will have become apparent,” writes Winchester, and this is perfectly reasonable. It is not his fault that we are in a phase when the book, with its lead times — its production cycle of editing, printing and distribution — is ill-equipped to comment on machine intelligence’s exponential growth spurt. To try is like chasing after an accelerating car.

Earlier in the book, Winchester quotes Tennyson’s Ulysses,

yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

The irony is that we are all Ulysses now, past the Pillars of Hercules and gazing wonderingly at a horizon we can never exceed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.