Is occult knowledge even possible in the age of the internet? If a recondite author obsessed you back in the day, it took hours of fossicking in far-flung dusty bookshops to feed your hunger. Oh, the joys of hunting down a shabby collection of Arthur Machen weirdiana! Now a few keystrokes will do the job. The magic has been lost.

Magic is Alan Moore’s business, and he’s also a Machen devotee. The graphic novelist is well known for issuing his illustrators with exceptionally detailed written instructions for series such as The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and From Hell, which perhaps accounts for the throbbing prose style of this fantasy novel. While the notion of an alternate London is not new (see, for example, China Miéville’s Un Lun Dun), The Great When is a tasty stew of Moore’s influences, such that fans can tick them off on their fingers and newcomers can delight in its rich savor.

First you have to get through the opening pages. Even Ulysses offers an easier start. Aficionados will recognize the two seniors in conversation as Aleister Crowley and Dion Fortune; but what’s this African racing tipster doing on the next page? Then the surrealist poet David Gascoyne at the Battle of Cable Street, seemingly witnessing Delacroix’s Liberty leading not French revolutionaries but anti-fascist rioters? It might be best to skip these passages (they will make sense later) and go straight to “The Best Way to Start a Book,” with its references to George Orwell, whose Nineteen Eighty-Four has just come out.

Our hero is timid Dennis Knuckleyard, 18 years old. His adventures kickstart with, of all the hoary clichés, a cursed book. He works in Coffin Ada’s East End bookshop, and is dispatched by that harridan to buy some occult material from a dealer in Berwick Street as cheaply as possible. It’s a stack of Machens, wouldn’t you know, with a strange addition: a book called A London Walk by the Rev. Thomas Hampole. The vendor is keen to get rid of it, but the bonus tome sends Ada into a flap: “When I say this book’s not real, I mean it don’t cough cough cough cough exist. It’s not in catalogues. It’s not in libraries. Arthur Machen made it up.” (That’s why she’s called Coffin Ada. Or is it?)

So Dennis must return the volume quick smart, but Flabby Harrison’s already a goner, and meanwhile there are these other geezers taking an interest, some of whom are not of this world. A London Walk is a portable portal to an alternate London, mapped on this one, as wondrous as it is terrible, and Dennis is unfortunate for his first incursion being to Soho Entire, where even the detritus is carnivorous. These lengthy incursions are transcribed in italics.

Moore’s writing on London is delightfully astute: “Other districts… had a tendency to merge into each other without any necessary change of atmosphere. With Soho, on the other hand, you knew when you were there and when you weren’t.” And there’s a fine evocation of Fleet Street’s ancient hostelry Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese: “Inside the windowless retreat, where dawn and sunset were at best a rumor, the same endless 16th-century day was going on.” Moore credits Michael Moorcock and Iain Sinclair as inspirations, but I caught a flavor of the mordant wit of the late Christopher Fowler.

When a meeting is set up in Shoreditch by a gangster who unwisely wishes to do a deal with his Great When counterpart, “the abstract principle of felony,” Dennis is assured that no one will notice the irruption of the otherworldly:

Normal people, they can’t let themselves see things like that… If there’s somebody tonight who’s thinkin’ about walkin’ ’ome through Arnold Circus… they’ll decide to go another route. Nah, passers-by, least of our worries.

An elegant deployment of the sixth sense necessary for the urban night-walker.

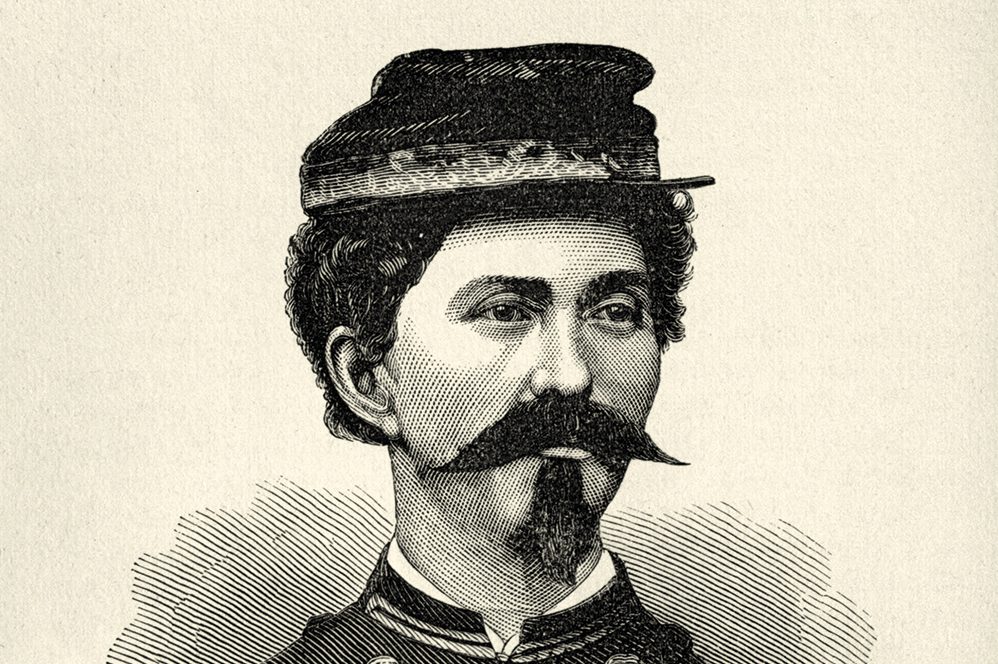

The artist and magician Austin Osman Spare (who featured in Moore’s graphic novel Promethea) can, like other “artists, poets, nutters,” move between the worlds, but Dennis is one of those normal people and his experiences there come close to destroying him. A seemingly benign character is too obviously a baddie, and I am also deducting points for the only two significant females being a prostitute and a hag, even if the former knows words like “anamorphic.” At least Moore is neither flippant nor lascivious about her grim trade.

Readers’ own tastes will determine whether “Knuckling a residue of dream from clotted sockets he somnambulated his way down the stairs” (getting up) and “Unseen stagehands wound a canvas backdrop past, a crawling frieze of buildings hyphenated here and there by rubble” (walking down the street) are luscious or ludicrous. I loved it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.