The Maldives is an unusual country. It’s Asia’s smallest country, but also the world’s most geographically dispersed. It has Asia’s second smallest population, but is one of the world’s most densely populated. It was Buddhist for a millennium and a half, which is conspicuous in most of the country’s ruling institutions, early scriptures and even language, but you wouldn’t know it from the people; it’s almost 100 percent Muslim now, demographically and culturally, and has been since the last Buddhist king of Maldives, Dhovemi, converted in 1153 (or maybe it was 1193 — depends on who you ask).

If someone mentions the Maldives, your first thought is either that it’s a beautiful tropic holiday paradise, or it’s sinking, as one of the most at-risk countries from climate change and rising sea levels.

When I visited in May, the weather was good and the ground was dry. My first stop was the Jawakara, a family-orientated resort boasting 290 villas nestled in the Lhaviyani atoll. There are beach villas and water pool villas and family villas, a walkway between the islands Mabin and Dheru, courts for paddle, pickleball, badminton and tennis, the largest golf course in the Maldives, six restaurants (from Asian fusion restaurant Umi to buffet restaurant Vela) — and of course, the inclusive Suhla spa.

There have been propositions to build sea walls around the islands, to shield it from the effects of climate change, and scientists are concerned that the increasing tides will eat away at the country’s famous, beautiful sand.

My villa had a private pool and an outdoor rainforest shower, if the shimmering Indian Ocean — an inconvenient ten-second walk away — wasn’t good enough for me. The sister resort, Hurawalhi, has spas built into the rooms. I was given Champagne on arrival, and harpists played out my first night by at the beachfront bar. I fell asleep during my Balinese massage. It didn’t feel like a place bracing for environmental destruction. It felt like a Love Island set.

In 1988, local authorities claimed that the rising sea level would swallow the country whole within thirty years. Then in 2012, former president Nasheed said it would be “under water in seven years.” Aside from the 5.8 Undersea Restaurant — where diners can feast on a set seven-course menu, looking out on a coral reef — it’s still not underwater.

One way to look at this is that it was all delusional alarmism, ill-informed panic that didn’t bear fruit, but everyone’s too embarrassed to acknowledge they got it wrong. That would explain why new resorts, like this, keep building out toward a sea that’s supposed to be edging closer.

But maybe they’re just stuck. Maybe doom is on the horizon, but an economy built on tourism and an image of tropical paradise can’t acknowledge harsh realities and start erecting sea walls, so we should all just keep drinking and dancing, and hope we’re not there when the music stops. I was woken up the next morning by a floating breakfast of pastries, fresh fruit and more Champagne. I was able to visit the relatively untouched island of Olhuveli, away from the frequented tourist spots, with its colorful pastel houses and friendly locals; but the fact I was shown it, and visited it, just shows that its nature as “untouched” “authentic” Maldives is just another sell for tourists.

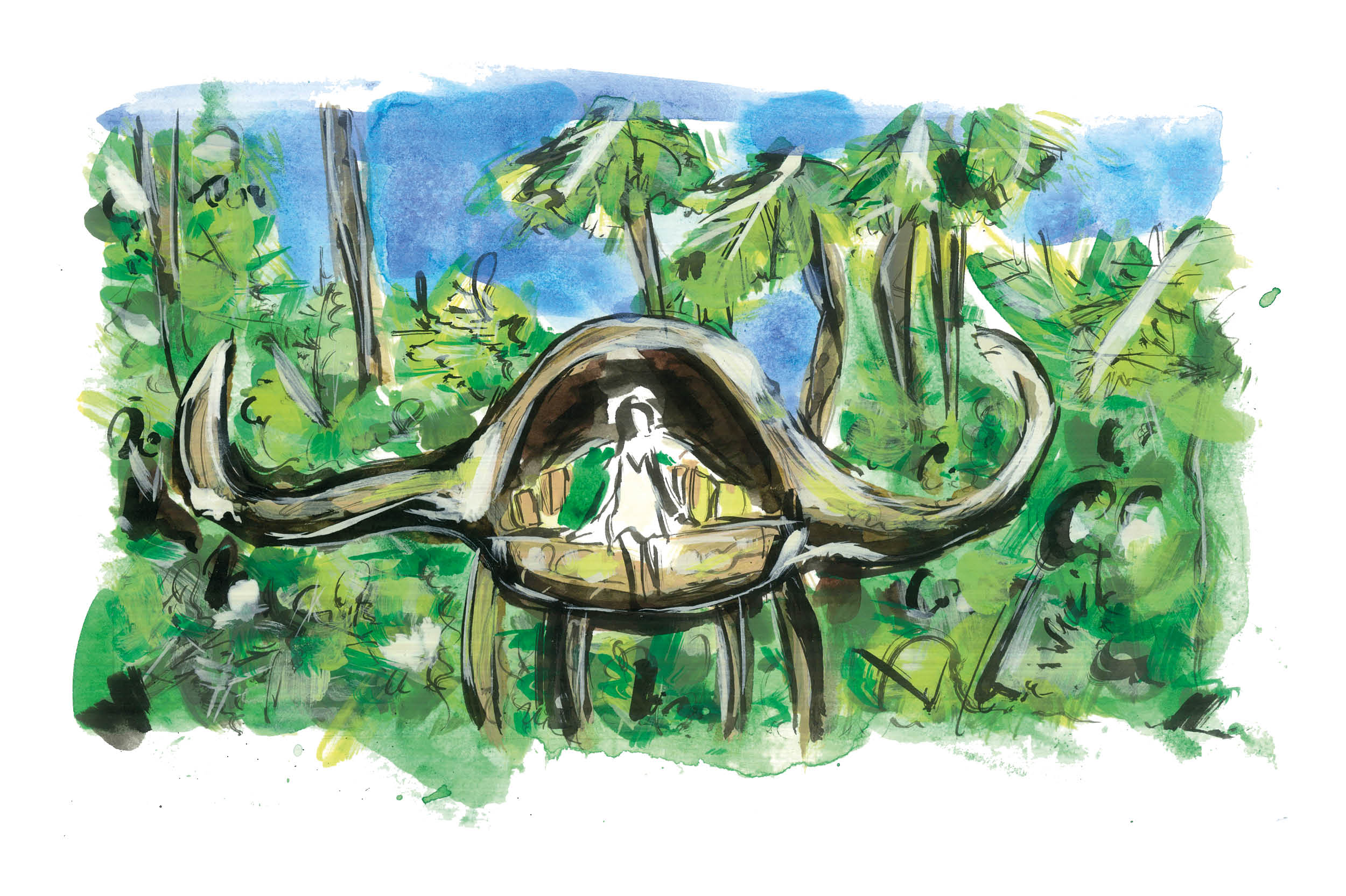

At Kagi Resort — the “Spa Island” — I snorkeled in in the reef, and had the most delicious bread in my life at the Baani Spa Corner, after a fifty-minute traditional massage, and swam in the Maldivian sea, straight from the backdoor of my Ocean Pool villa, as the quintessential way to work off the Taittinger-fueled hangover. Where I was a Love Island contestant on Jawakara, here I became Gwyneth Paltrow, meditating in the ocean-side tranquility and wellness of it all.

I was at peace. I was rested. I was whole. The lapping of the waves eased my mind, and let me forget about the world. They didn’t sound like they were going to consume me, and wash away this whole island and country and illusion.

Leave a Reply