Africa Orientale Italiana

“Where did you get those glasses?” a stylish Italian gentleman asked me, gesturing at the acetate L.G.R. frames I wear for my myopia. I said Nairobi. “Good,” he said, “I make them.” Luca Gnecchi Ruscone and I then had a conversation that brought back fond memories of adventures across the Horn of Africa, all focused through a history of spectacle lenses. Astigmatism and short sightedness has been with me since I was thirteen in England, when I was forced to start wearing those heavy, black-rimmed NHS 524 specs. The singer Morrissey later made them seem cool, but I remember always taking them off to stumble blindly around at school dances so as not to frighten the girls.

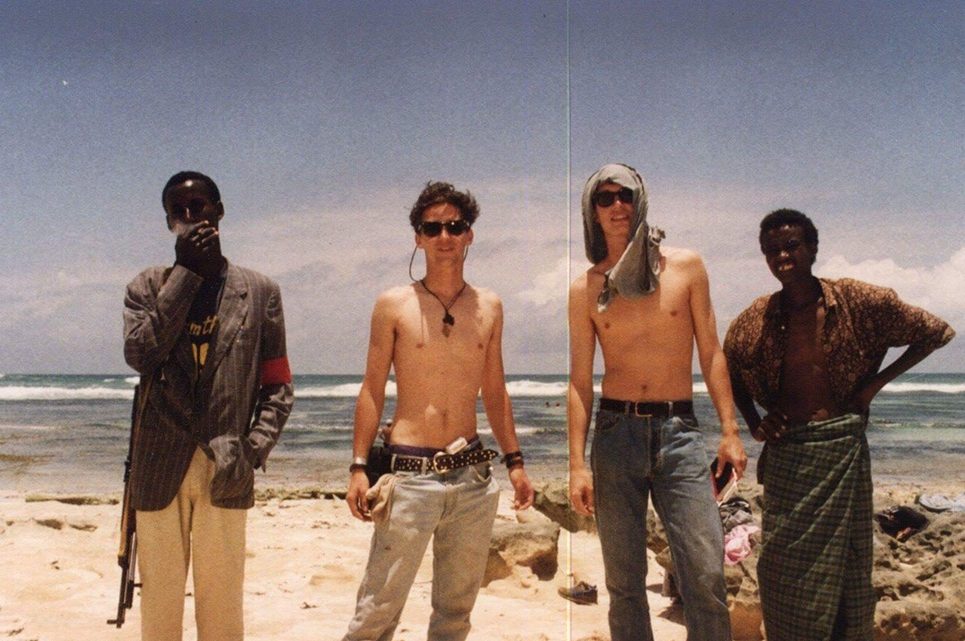

‘Human blood is so corrosive to paint,’ said the rebel commander to me from behind his Persols

As an undergraduate I fell in with men who wore corduroy jackets, smoked black tobacco and rarely ate food, so circular metal-rimmed eyeglasses went with the gaunt Bohemian style. As a foreign correspondent in Africa, I stuck with the metal frames, until one day the police beat me up during a democracy riot on the streets of Nairobi. A large-fisted officer bashed my glasses into my face, so that the nose pads and metal wires ripped into the skin. Thereafter, I opted for plastic-framed glasses and ever since, during riots, interrogations and bar brawls, this has turned out to have been the right decision.

Around this time, when the Berlin Wall fell, several horrible African conflicts that had long been fueled by West and East spiraled into state collapse. In Somalia, clan militias raced around in Landcruiser pickups mounted with anti-aircraft guns they fired horizontally at infantry, leveling the old city around the ruins of the cathedral and Umberto di Savoia’s grenade-spattered arch. Over their Gaggia-made espressos or plates of spaghetti, local warlords ordered raids on famine camps — and everybody wore vintage shades left behind by the Italians. In a city where you could still find Beretta pistols, Vespas and Fiat 500s, the markets were full of sunglasses.

Dan Eldon, my photographer friend, favored Persol Rattis, with their silver arrow design in the black frame, while I liked Rayban Wayfarers with prescription lenses. For many years after that, I always put my day-to-day lenses into Raybans or Persols. There’s a photo of Dan and I together on a Mogadishu beach with some militias, both wearing our shades, shortly before Dan was murdered by a Somali mob in the aftermath of a US Cobra helicopter strike. Of course, cool shades always defined African failed-state fashion. Zaire’s Mobutu wore Celine with his leopard skin fez; Mugabe sported Cartier; Liberian war criminal Charles Taylor liked police girlwatchers, while Gaddafi kept a selection of shades to go with his gold epaulets, bisht, medals and Cuban heels.

The story now moves to Eritrea, where Luca Gnecchi Ruscone’s grandfather Raffaello Bini arrived in 1936 as a photographer covering Mussolini’s war against Abyssinia. He fell in love with Africa and so, after the war, Nonno Bini stayed on in Asmara, where he established Foto Ottica Bini, which sold Leicas, film and sunglasses. On my first journey to Eritrea in 1990, I witnessed the battle for Massawa, when the communist garrison fell to the rebels, who set up their headquarters in the stunningly beautiful Melotti family home on the Red Sea. Like the Binis, the Melottis had done well in business, running a brewery, but during the civil war the Italians had been forced to flee. After weeks in the desert, I wanted to leap into the Melottis’ lovely swimming pool until I saw the gory outline of a corpse on the floor of the piscina. “Human blood is so corrosive to paint,” said the rebel commander to me from behind his Persols, explaining that the phantom shape in the pool had been made when a communist officer had shot himself in the head rather than surrender. His body had been left to float around in the water, before settling on the bottom.

In 2005, Raffaello Bini finally returned to Eritrea, accompanied by his grandson Luca. On entering the shuttered Foto Ottica Bini, they found among the unlooted inventory — no doubt covered with dust from the Danakil — a collection of vintage sunglasses. Entranced by their style, Luca returned to Italy with these frames and established L.G.R, which employs small artisanal workshops to handmake glasses inspired by the styles that he found in his grandfather’s Asmara optical store.

I, meanwhile, had over the years found it increasingly difficult to find spectacle frames that paid tribute to the style I liked — Horn of Africa militia chic — until last year, when I found quite by chance a pair of L.G.R.s in a Nairobi optician. I had no idea that my choice of glasses would in some way be inspired by Luca’s own love affair with Africa. He names his designs things like Zanzibar, Djibouti, Marrakech and Asmara — and he does very well indeed.