The late Henry Kissinger said of the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s that it was a shame that both sides couldn’t lose. Much the same is true of the current situation in Syria, where the long established regime of the brutal but secular Assad dynasty has fallen to a sudden Islamist rebel offensive.

Syria has been convulsed by a vicious and multi-sided conflict since 2012 when riots against the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad turned into a full-scale civil war. Assad, a London trained ophthalmologist, had reluctantly become the heir apparent to his iron-fisted father Hafez al-Assad (the last name means “the lion”) after the death of his more political brother Bassel in a car crash.

Recalled from Britain, Bashar soon grew into the dictator’s role, however, and since Hafez’s death in 2000, has proved every bit as brutal and ruthless a ruler as his father. Hafez, like Saddam Hussein in neighboring Iraq, rose to power in a series of coups in the 1960s on the back of the Ba’ath Party — a secular and socialist Arab nationalist movement opposed to both Islamism and western domination.

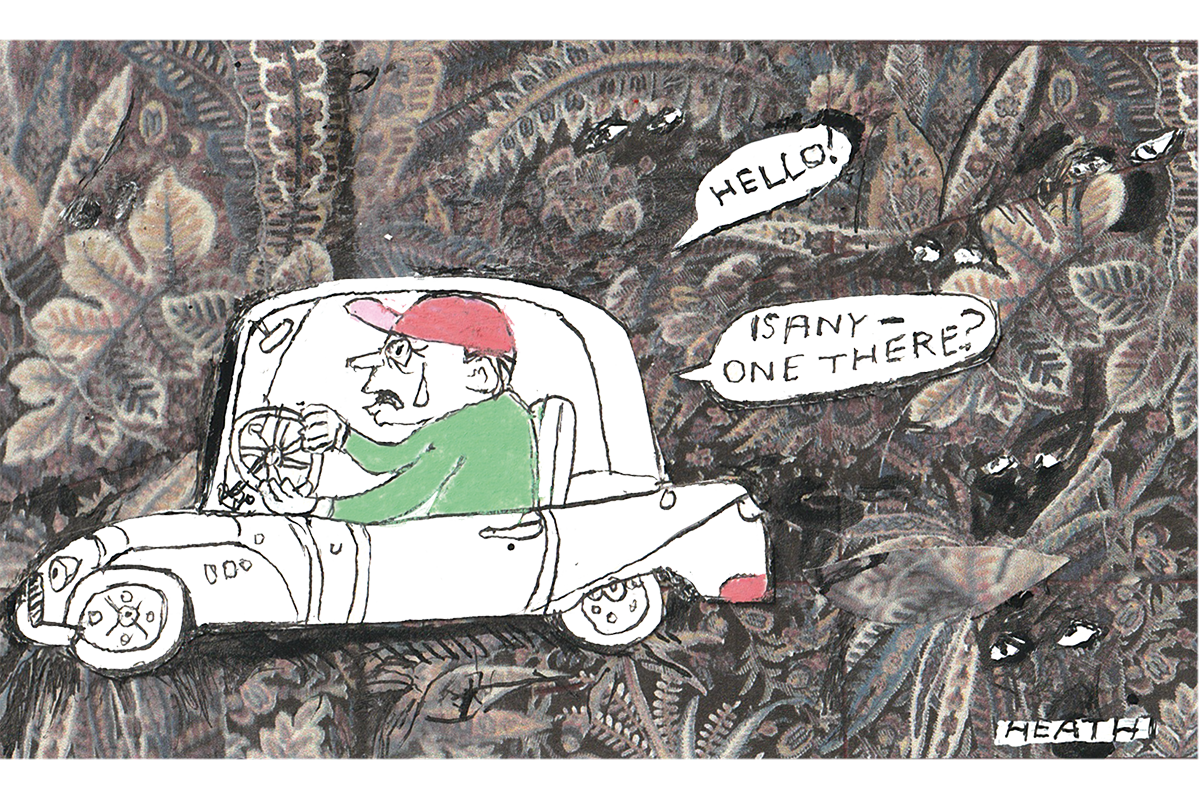

Will Syria’s new rulers restrain their followers?

The regime he established was a one-party dictatorship dominated by the Assads’ own minority Alawite sect. The Alawites are a breakaway offshoot of Shia Islam, regarded as heretics by the Sunni majority in Syria who make up perhaps 75 percent of the population. The Alawites comprise only around 15 percent, and there are also significant Christian and Druze communities in the country.

When Syria was a French colony between the world wars, the French favored the Alawites as part of a divide and rule policy, and promoted them to influential posts, particularly in the military. Hafez al-Assad was originally an Air Force officer, and today the Alawites hold all the key positions in Syria’s armed forces and its feared secret police, the mukhabarat.

The Alawite dominance naturally bred resentment among the Sunni majority, and in 1982 fuelled an uprising led by the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood in Hama, Syria’s fourth largest city, which was savagely crushed by Hafez’s army and Alawite militias with the deaths of up to 40,000 people in the city.

This week, Hama was seized by the Islamist HTS rebel movement, who released fellow Islamists imprisoned in the city jail who vowed vengeance against the Assads with the chilling words “May their hearts burn.”

Any westerner traveling in Syria before the civil war broke out was struck by two things: the fact that the country is probably the most westernized and secular of all Arab states, with women walking freely on their own in western clothes, and a pervasive fear of the regime, which had established stability with a pervasive police state. Mukhabarat agents were everywhere.

The anti-Assad forces who finally rebelled in 2012 were a ragbag coalition ranging from Islamist fanatics linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State and western-backed liberals looking to establish democracy. Soon the Islamists became predominant, enabling the regime to portray them as “terrorists” and making their western backers uneasy. In 2013, Britain’s Parliament narrowly voted against David Cameron’s attempt to intervene in the civil war on the anti-Assad side, and then-President Obama used this as an excuse not to join in either — although Assad had crossed his “red lines” and used poison gas against the rebels.

There were no limits to Assad’s violence against his own rebellious people. Torture was routine in the regime’s jails, and human rights monitors estimate that 32,000 have died in them as a result. Despite such repression, the rebels made sweeping gains across the country, seizing its second city Aleppo and even capturing swathes of the ancient capital Damascus.

It looked then as if the regime was about to fall, but the Assads have been a close ally of Russia since the Cold War, and Putin was unlikely to let his naval bases on Syria’s Mediterranean coast around the port of Latakia — the Alawite heartland where the Assads hail from — fall into hostile hands. Russia intervened militarily on a massive scale to save his ally, as did Iran, the world’s leading Shiite power, along with its Lebanese proxy Hezbollah.

Russian planes pounded Aleppo’s center to rubble with barrel bombs, and Hezbollah fighters crossed from Lebanon to help the regime retake the city. By 2020 the war had reached a stalemate, with the regime holding all the major cities and most of the ground between them, while the rebels were penned into Idlib province near the Turkish border where Turkey’s President Erdoğan was battling Kurdish militants who had also got involved in the Syrian conflict.

All that suddenly changed last week when in a carefully planned surprise offensive the main rebel group, the Turkish backed HTS, erupted out of Idlib and retook Aleppo in a matter of hours. The situation today is dramatically different from 2014: Putin’s armies are fully occupied with their war against Ukraine; Iran is otherwise engaged in its undeclared conflict with Israel, and Hezbollah has been crippled by Israeli air strikes.

The situation is shifting with dramatic speed; after HTS’s seizure of Aleppo and Hama, they closed in on Syria’s third biggest city Homs. Damascus followed last night.

Russia has already advised its citizens to leave Syria, but the collapse of Putin’s client regime in Damascus represents a huge and humiliating defeat for Moscow and a major strategic setback for both Russia and Iran.

More serious still, will Syria’s new rulers if they win restrain their followers from massacring the Alawites who have lorded it over them for so long? The HTS leader, Abu Muhammad al-Julani, who decoupled his movement from al-Qaeda and rebranded it in more moderate colors in 2016, has assured Syria’s non-Sunni minorities — including Christians — that they have nothing to fear and can continue to worship unmolested, but the record of Islamist takeovers elsewhere in the region is not exactly reassuring.

Even if there is not outright genocide, there is bound to be a thirst for revenge against Assad’s Alawites, and almost inevitably another mass migration by waves of refugees from the devastated country lapping on Europe’s shores.

Leave a Reply