Loving the films of the Italian auteur Paolo Sorrentino, I thought he’d be easy to chat to. But a maestro is a maestro, as I was reminded when I interviewed him in London last week. Masked and communicating through a translator, I semaphored my admiration for his new film The Hand of God, starting with its spectacular opening shot. Like a bird, the camera flies over the sea, then focuses on a vintage car tooling along the promenade, before panning over the city again. But he rejected my praise: “It’s not complicated. It’s a normal shot by helicopter.”

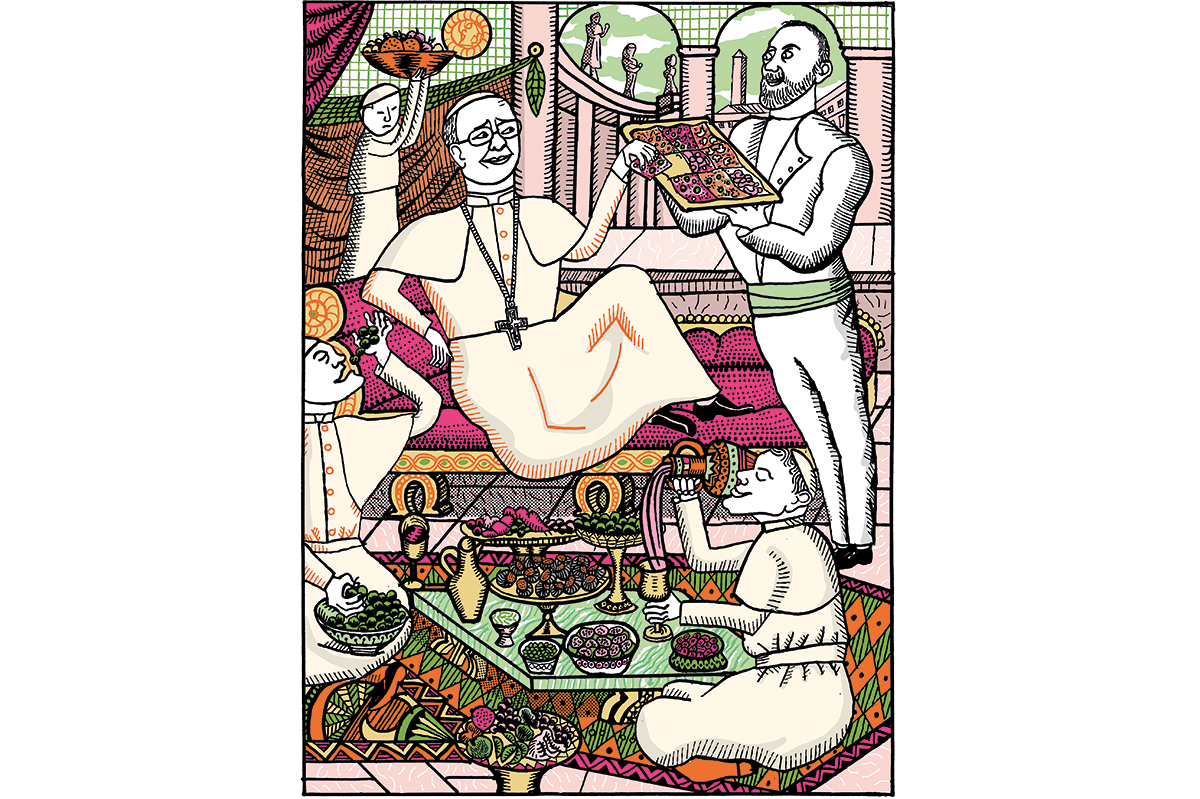

He’s right, of course, that his new classic coming-of-age story represents a departure towards simplicity. Gone is the virtuoso editing of his 2008 political movie Il Divo, gone the baroque of The Great Beauty, his Oscar-winning 2013 ode to Rome, which conjured a giraffe in the Baths of Caracalla and a disco bacchanal overlooking the Colosseum. “I always did a very complicated and tricky mise-en-scène and I thought, maybe this is the moment and the right script to do something simple and easy. This story I had in my mind for many years but I never found the courage to do this movie.”

Set in 1980s Naples, The Hand of God tells the true tale of how Sorrentino lost his beloved parents the year he turned seventeen. The technical side might be more “simple” but the emotional daring is high. Humor and tragedy are often simultaneous, as Sorrentino evokes, with impressive lightness, how Maradona saved his life. If he had not stayed in Naples to see their new star player, he would have been with his parents when their fatal accident occurred.

This deeply personal material welled up around the time Sorrentino turned fifty, a year and a half ago. “I was ready to look at my past without anxiety or much pain,” he says. Why? He looks at me discouragingly. “I don’t know why, I never did therapy or analysis, so I don’t know myself very well.” But he went into more detail in a private Q & A that evening, explaining how it all began while he was drafting The New Pope, sequel to his powerful HBO series The Young Pope, with Jude Law and Diane Keaton. “Suddenly I found I was very tired to write about cardinals and bishops.” So he wrote The Hand of God script over forty-eight hours with the idea that he would let his son and daughter (now aged eighteen and twenty-four) read it “so they could understand why I am, in my opinion, ‘weird’”.

He wrote quickly because “I didn’t invent almost nothing.” Even the near-miss encounter with Fellini, which seems like an allusion but isn’t: his older brother Marco had an audition with him, while the young Paolo waited outside, all eyes, all ears.

The Bay of Naples is a rich and potent backdrop, but my have-a-go question about growing up so near Vesuvius misfires. “This informs my personality? I am not able to answer your question without saying stupid things.” Asking if one scene is shot in Capri’s Blue Grotto is slightly better tolerated: “Yes, the best place you can swim in Capri is La Grotta Azzurra, of course, that was where I used to swim, except it’s closed now, so you can’t any more. We shot at a different grotto.” My final mistake is asking if Naples — in the spotlight again with Maggie Gyllenhaal’s adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter about to appear on Netflix — is itself a character. “What does this mean? It doesn’t speak, it doesn’t cry. It’s a place, it was countryside, now it is buildings, it’s not a character…” Well, I guess you don’t get to be an internationally regarded auteur by being accommodating.

Perhaps he is tense because it is such emotional subject matter, so close to home — literally, as many scenes were shot in the actual apartment block in which he grew up. “We found the apartment below mine belonged to an old lady who never changed it. I was very surprised to see it the same.” Production designer Carmine Guarino “exactly” recreated the nautical-themed bedroom he shared with his brother. The warmth and love of his family flows so naturally through the film until it is cut off, in a tender, unforgettable death scene which I can’t bear to force him to discuss.

But on stage that evening with director Alfonso Cuaron, he explained how during the shoot he struggled to keep his emotions in check. “I was afraid to cry in front of fifty people, this was a nightmare for me. So I said OK, I must pretend everyone is playing a character and that I invented them as I did in other films. But I didn’t succeed always, in the scenes in the hospital or in the cemetery I was forced to run and hide myself behind a monitor.”

He also said his stylistic “key’ to The Hand of God was Cuaron’s 2018 movie Roma (not Fellini’s autobiographical Amarcord, which he seemed vaguely irritated that I mentioned). “When I watched Roma I thought this is a good way to do a personal, intimate movie without being rhetorical and without all the traps that an autobiographical movie can present.” These traps he elucidates as “hyperbole, victimhood, pity, compassion and the indulgence of pain,” to be avoided through “simple, sparse and essential staging. With neutral music and photography.” No wonder he didn’t like me praising the showy opening shot.

I noticed his wife, Daniela D’Antonio, in the back row, keeping an eye on everything, smiling. She is head of communications for the film production company he works with. When The Hand of God won the Silver Lion at Venice this year, he called her his golden lion. “She helps me a lot, with everything. Gives advice, share the moment of joy, stay with me.” Because, as he told me, “making a film is very difficult, it’s objectively a very complicated final object. There is a lot of money so there are many interests.” Is he a benevolent dictator on set? “I try to be kind but sometimes I don’t succeed, like any human. You have to carry this machine forward with a hundred people working on it. It’s not that you have to be scary, you just have to know what you want. Exactly what you want.”

The Hand of God is in cinemas now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.