It was recently announced in the Daily Telegraph that the novels of P.G. Wodehouse — much beloved by millions, including me, for their combination of wit and soufflé-light evocation of an England that never really existed but which almost might have done — are the latest to fall foul of that new scourge of writers the world over, the “sensitivity reader.” New editions of Wodehouse’s masterly works Right Ho, Jeeves and Thank You, Jeeves have been reissued with the craven disclaimer “Please be aware that this book was published in the 1930s, and contains language, themes and characterizations which you may find outdated. In the present edition, we have sought to edit, minimally, words that we regard as unacceptable to present-day readers.”

In practice, as usual, this has meant that unacceptable racial terms have been quietly edited out, and although the disclaimer goes on to state that these alterations “do not affect the story,” there is no doubt that the latest changes to Wodehouse’s work represent that most regrettable of modern-day phenomena: the posthumous editing (some would call it bowdlerization, and they are not wrong) of authors’ work, without their knowledge or permission, to bring it closer into line with modern sensibilities. Whether or not Wodehouse would have reacted to this with horror or shrugging acceptance — he was always pragmatic about the reception of his work, although he kept a surprisingly sharp eye on his royalties for one who claimed to be quite an unworldly fellow — cannot be known, but it is likely that, to quote Bertie in The Code of the Woosters, “I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.”

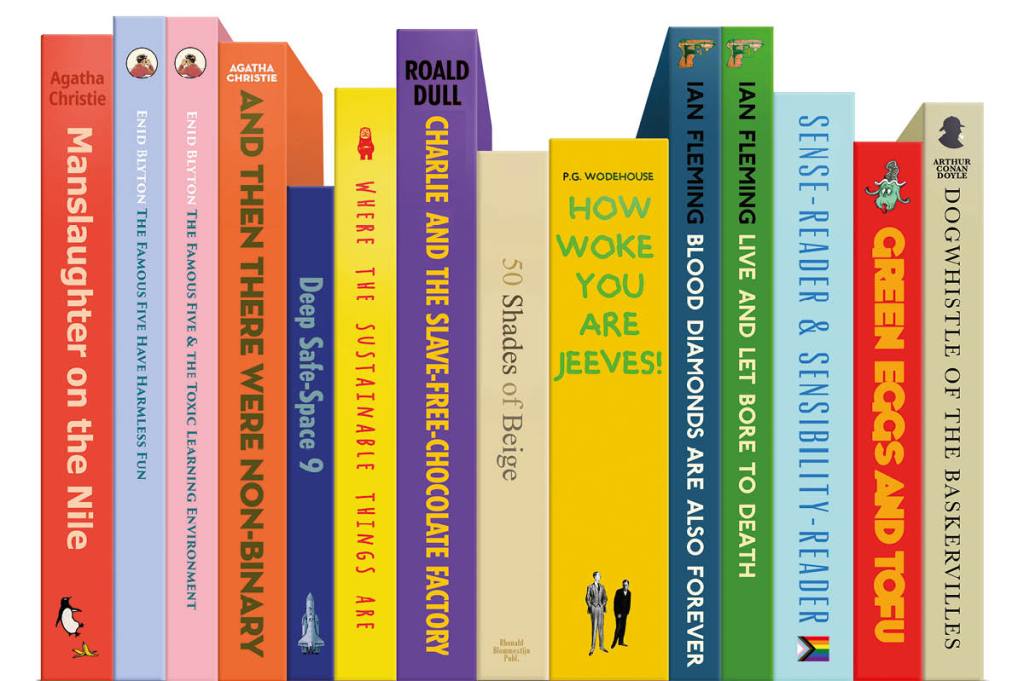

The author once known as “Plum” is not the first victim of this sharp-scissored practice, either. Roald Dahl, Ian Fleming, Agatha Christie and Enid Blyton — four of the bestselling authors of the twentieth century, and beyond — have all been similarly censored by publishers anxious not to offend potential readers. In the case of Dahl, the changes were so drastic and vast that at times they affected the sense and cohesion of his books, and so, after a considerable outcry in both Britain and America, it was cravenly announced by his publishers Penguin Random House that the original, uncensored versions of his children’s novels would be available alongside the “enhanced” ones. As PRH children’s managing director Francesca Dow commented, “By making both Puffin and Penguin versions available, we are offering readers the choice to decide how they experience Roald Dahl’s magical, marvelous stories.”

The Dahl backlash has meant that it’s more likely than not that the original versions will continue to be read, and the sensitivity-reader editions will almost certainly die a quiet death. Yet in the case of the other authors, who have not enjoyed the same wellspring of publicity, it seems that the “revised” titles are likely to become the norm. (Even so, none other than Queen Camilla pointedly commented, at a literary function, “Please remain true to your calling, unimpeded by those who may wish to curb the freedom of your expression or impose limits on your imagination. Enough said.”)

In some cases, these alterations cannot be said to be a bad or undesirable thing. Christie’s famous novel And Then There Were None was originally, notoriously, titled Ten Little Niggers, which was then altered to Ten Little Indians; hardly much of an improvement, and so its latest incarnation (a far better and more enticing name than either of the other two) would only offend the most dyed-in-the-wool conservative. And the Ian Fleming estate provided a robust and, to my mind, convincing explanation for the various alterations to the most recent reprint of the James Bond novels. The estate posed the question: “As the author’s literary estate and now publishers, what responsibility did we have, if any, to review the original texts?” It went on to suggest that “rather than making changes in line with [external parties’] advice, it was instead most appropriate to look for guidance from the author himself. The original US version of Live and Let Die, approved and apparently favored by Ian, had removed some racial terms which were problematic even in mid-1950s America and would certainly be considered deeply offensive now by the vast majority of readers.”

This became the touchstone for any edits or changes made; as the Fleming estate described it, “we took that as our starting point, but felt strongly that it was not our role to comb out every word or phrase that had the potential to offend… some racial words, likely to cause great offense now, have been altered, while keeping as close as possible to the original text and the period.” The changes, which the estate stressed are “very small in number” do not apply to all of the James Bond novels, and while there is an argument to be made that the books should remain as they were during Fleming’s lifetime, there is also a persuasive counterargument that, if the author himself was fully prepared to make changes to his own work, those who have taken on the mantle of publishing and publicizing his writing are acting as he would have wanted them to.

Literary estates are a strange phenomenon, however. I wrote recently about the secretive and powerful J.R.R. Tolkien estate, which has consistently frustrated a definitive biography of the author and instead licenses posthumous titles that increasingly seem to bear less and less resemblance to the books that Professor Tolkien himself created. One can only imagine that, should the descriptions of orcs and goblins from The Lord of the Rings be seen as too explicit or offensive, they would be altered without hesitation, if there were any question of the lucrative brand being damaged otherwise. And the T.S. Eliot estate was managed with vigor by his widow Valerie until her death in 2012; this vigor included frustrating quotation from any of Eliot’s poems by biographers and critics, which means — as with Peter Ackroyd — that the enterprising were driven to near-desperate lengths to get round this stricture. (“Turn to the collected edition, page 43, line 4, third word…”) However, at least the Eliot estate’s almost farcical rigor when it came to the protection of the author’s interests meant that there has been no attempt — to date, anyway — to censor or cancel his poetry. When the Dahl controversy first broke, I mentally compiled a list of authors I expected to be in the firing line of sensitivity reads before too long. Some, including Fleming and Wodehouse, seemed obvious, and now it has come to pass. Yet there are many more major twentieth-century writers whose controversial personal lives and the contents of their books may yet become enmeshed. Evelyn Waugh, Kingsley Amis, Philip Roth, Philip Larkin — all, surely, are destined for the twitching green ink of the cancellation clerk before too long. And even Virginia Woolf, the patron saint of feminist writers everywhere, may yet be in the firing line, given some of her less acceptable opinions. The question now is where this all ends. I don’t believe that the relatively mild changes to the Wodehouse and Christie canons will be sufficient for some, and it would not be too surprising were there to be another round of alterations in a decade or two, with less implicit apology and more assertion that contemporary readers should not want to read the old-fashioned, deeply problematic works of cis heterosexual white writers in their original, “unimproved” forms. And I can easily imagine that the likes of Waugh, Amis and Roth will be quietly allowed to go out of print as their dead male whiteness falls increasingly out of sync with the contemporary publishing world. I can only imagine what a sensitivity reader would make of Black Mischief or Stanley and the Women, and hope that they would take on the difficult task of “improving” such books armed with the contemporary equivalent of bell, book and candle: a support animal, a link to Meghan Markle’s Archetypes podcast and the certain knowledge that there will be a strongly worded press release about the iniquities of these dreadful, thoroughly unreconstructed authors.

As the author of several works of historical and literary biography myself, I have heard the chimes at midnight. There is, I believe, no way that any major publisher would now commission Blazing Star, a biography of my first subject, the decadent libertine poet Lord Rochester, without putting a great deal of finger-wagging about his bad and licentious habits into the book itself, or its author being someone who would explore Rochester’s queer identity at considerably greater length than I did.

But perhaps one day, many decades from now, a sensitivity reader will come to Blazing Star and thoroughly rewrite my book, correcting my outdated and deeply unfashionable opinions, and improving it beyond measure. All I can hope for is that I’m long gone by then, and far from the reach of such “improvements.” But for the rest, we can only hope that posterity judges dead authors’ original books considerably more kindly than the modish interlopers of contemporary publishing have done.

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.