How should we measure the value of a work of art or, failing that, a pop song? Take for example John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’, which was recorded exactly 50 years ago. It certainly scores on the sales front, having shifted about 21 million copies worldwide according to the Chartmasters service. That’s a healthy revenue stream in anyone’s book, particularly for a tune whose lyric urges us to envision a world without possessions.

The ‘ubiquitous’ box gets ticked, too, because ‘Imagine’ has been covered by more than 200 other artists. It’s the unifying song we all seem to turn to at moments of crisis, as when the pianist David Martello performed it in front of the Paris Bataclan the morning after the November 2015 terrorist attacks there. Jimmy Carter once modestly remarked, ‘In many countries around the world — my wife and I have visited about 125 countries — you hear “Imagine” used almost equally with national anthems.’ The radical author Kevin Powell is one of those on ground beyond this. At the height of last summer’s riots, Powell argued that ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ is ‘problematic’ because of its composer’s ties to the slave trade. Why not, Powell wrote, replace the tune with ‘the most beautiful, healing, all-people, all-backgrounds-together kind of song you could have’, as he called ‘Imagine’?

But is Lennon’s three-minute précis of the human condition actually any good? That’s a harder question to answer. Technically speaking, it’s pretty simple, even by pop music standards: a droopy, four-bar lullaby intro and some greeting-card pleas for universal brotherhood, all served on a bed of repetitively plunking piano distinguished by its austere clarity or childish naïveté, depending on your taste in these things. We’re not talking Stravinsky here, or even prime Beatles — the group that brought us all those great, early Sixties hits that managed to sound both rivetingly strange and comfortingly familiar, at least until the band were encouraged to take themselves too seriously. Perhaps the real secret to the song’s eternal popularity is that it taps into our modern obsession with feeling good about ourselves. There are no answers in ‘Imagine’, but with his simple question — can we free ourselves of our earthly hangups? — Lennon’s lyric defines the conversation that dominates today’s booming self-help industry. It’s truly a song for the ages.

The recording sessions for ‘Imagine’ began at Tittenhurst Park, the English Georgian mansion owned by Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono, in mid-May 1971. The home had 12 bedrooms and came equipped with half-a-dozen servants’ cottages, which as more than one critic has observed made it an interesting choice for a song that talks about the merits of ascetism. Besides Lennon, there were only two other musicians: the Beatles’ old Hamburg friend Klaus Voormann on bass and Alan White, soon to join the prog-rock outfit Yes, on drums. The English-born White now lives in the Seattle area and — I speak from at least brief personal acquaintance — remains the most natural, modest and unaffected of men, let alone of veteran rock and rollers. I recently asked him about the ‘Imagine’ sessions.

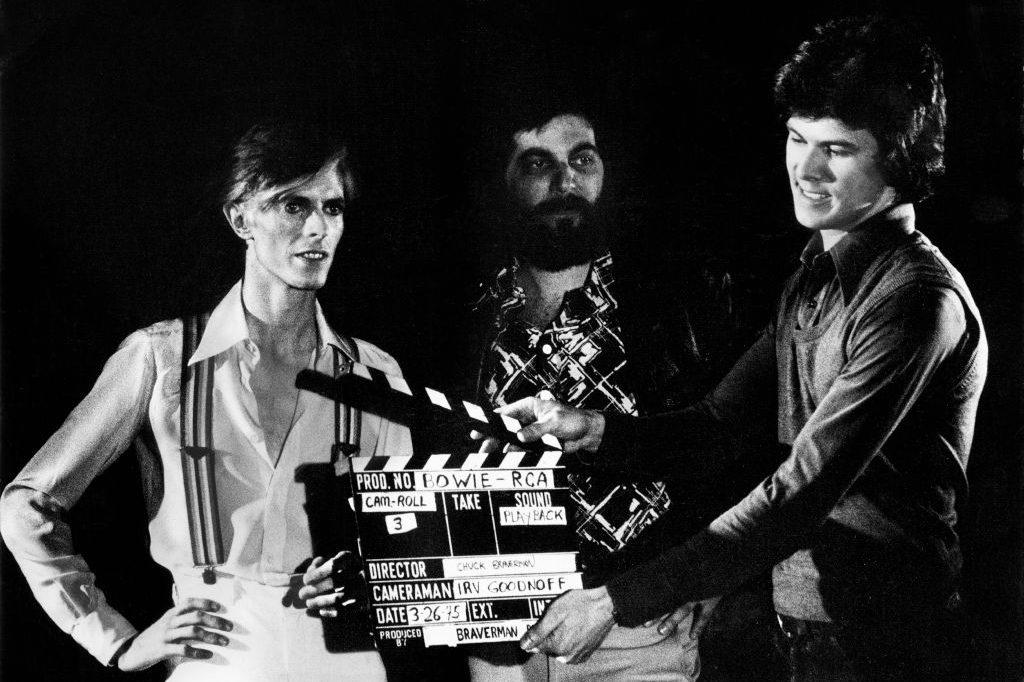

‘John wasn’t one for a lot of detail,’ White said. ‘He showed us the song’s lyrics, played it through on piano and we took it from there. I remember once he looked over at me and said, “Whatever it is you’re doing, keep doing it” and that completed the technical exchange. John and Yoko were both extremely gracious. I stayed as their guest at Tittenhurst for a few days, which obviously wasn’t too shabby for a 21-year-old musician living in a little house in north London. Other than that, I didn’t get paid.’Observing the ‘Imagine’ sessions from behind the window of a small control room was the legendary American producer Phil Spector, fresh from having infuriated Paul McCartney by lushing up the songs on the Beatles’ final studio album Let It Be without first mentioning it to their co-composer. This alone would have endeared Spector to Lennon, who had just been sued by his old songwriting partner in the High Court. Alan White remembers that ‘Phil just stood there, wearing a pair of shades, and didn’t say much,’ although he must have performed his knob-twiddling duties to Lennon’s satisfaction. ‘As we were leaving, I saw John hand Phil the keys to his Rolls-Royce and tell him “It’s yours”,’ White recalls.

Spector took the raw tapes of ‘Imagine’ to the Record Plant studio in New York, where they were scrubbed up and given one of the producer’s trademark orchestral washes. Released in October, the song was a worldwide hit in time for Christmas. By then Lennon himself had relocated across the Atlantic, leaving England for what turned out to be the last time on August 31, 1971. He later expounded on his song’s success: ‘It’s anti-religious, anti-nationalistic, anti-capitalism, but because it is sugarcoated it’s accepted… Now I understand what you have to do. Put your political message across with a little honey.’ In an open letter to McCartney, he added that ‘Imagine’ was ‘“Working-Class Hero” with sugar on it for conservatives like yourself.’

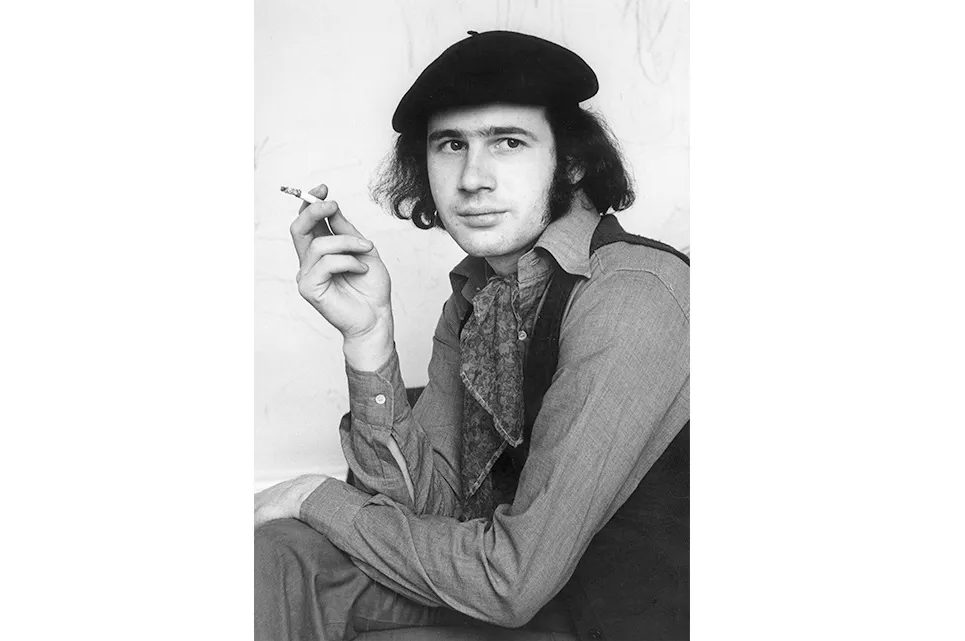

Like almost anything in pop that’s any good, ‘Imagine’ owed a debt to several predecessors. As Lennon himself once noted when accused of plagiarism, ‘It’s not a rip-off, it’s a love-in.’ Since his lawyers are famously robust when it comes to protecting their late client’s reputation, perhaps it’s best merely to say that the single greatest unacknowledged contributor to the song was Yoko Ono herself. Several years before she met her future husband, Yoko had self-published 500 copies of a book full of absurdist humor called Grapefruit. Speaking on December 6, 1980, two days before he was struck down by a madman’s bullet, Lennon had this to say on the subject:

‘Actually, “Imagine” should be credited as a Lennon-Ono song, because a lot of it — the lyric and the concept — came from Yoko… It was right out of Grapefruit, her book. But when we recorded the song I just put “Lennon” on it because, you know, she’s just the wife and you don’t put her name on, right?’

Apparently someone at the National Music Publishers Association belatedly read these words, because in June 2017 the organization announced that the song would henceforth be listed as a Lennon-Ono composition. It’s of course quite right that this should be so, although curiously this is the same Yoko Ono who had previously threatened legal action to stop Paul McCartney from altering the credits of several classic Beatles songs to ‘McCartney-Lennon’ instead of the traditional ‘Lennon-McCartney’. At the time, Yoko called the suggestion ‘ridiculous’ and added that it was ‘totally inappropriate’ to change a song’s authorship so long after the fact. Earlier, Yoko had seen fit to veto a request from McCartney to reverse the credit on the song ‘Yesterday’, a tune on which her husband didn’t play a single note, but which has nonetheless provided a healthy royalty flow to Lennon’s estate for the past 56 years. Imagine.