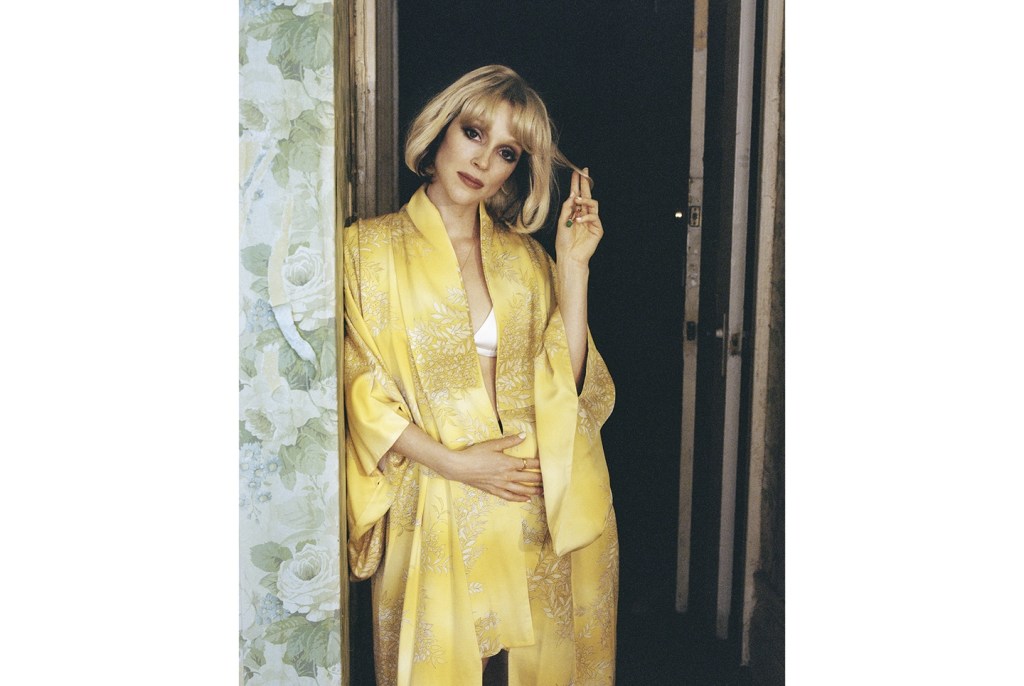

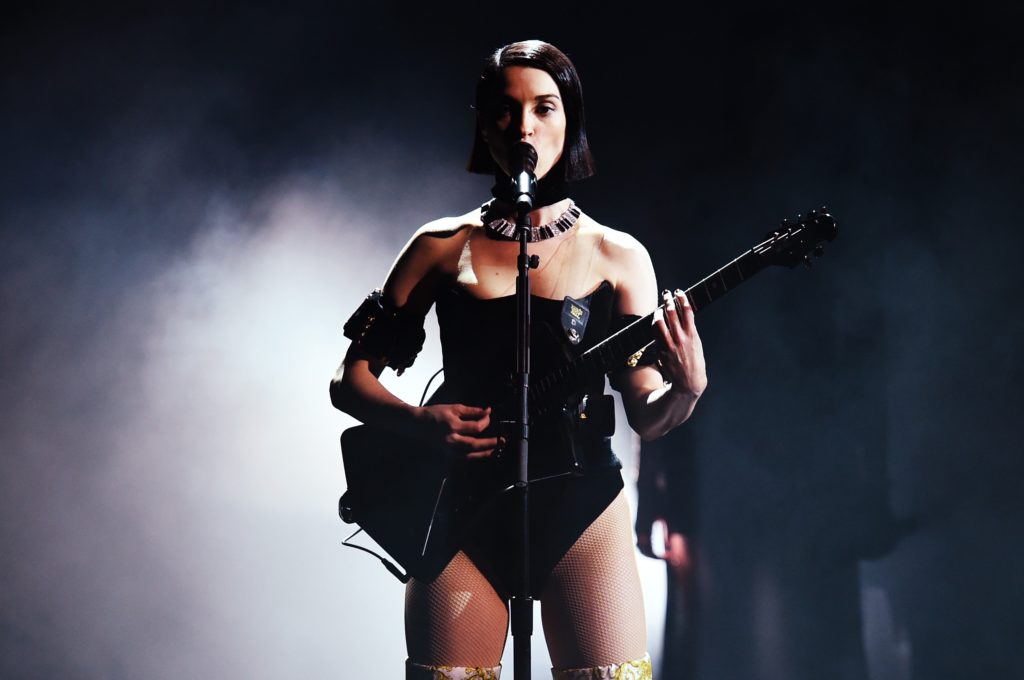

St Vincent — Annie Clark, a 38-year-old singer-guitarist of prodigious gifts — spends a lot of time confounding people. She confounds them with stage shows that are less gig than theater, ostentatiously choreographed and fabulously provocative (though not in any crude sense). She confounds them with an image that morphs from album to album (for her sixth, Daddy’s Home, she has adopted the dissolute Cassavetes-heroine look). She confounds them by, in a puritan age, placing sex squarely within her work, though usually in a plausibly deniable way (the title Daddy’s Home refers to her father’s release in 2019 from prison after serving nine years for his part in a stock-manipulation scheme. She says of the title: ‘It’s pervy’). She confounds them by being private and elusive, by refusing to be pinned down on her sexuality, while also entering into relationships with celebrity A-listers Cara Delevingne and Kristen Stewart.

And she confounds with her music, too, which shifts shape from record to record. One of the great pop and rock guitarists of her generation, she now rations her solos pretty strictly, but when they hit, they hit hard (on Daddy’s Home, ‘Live in the Dream’ features the best David Gilmour solo ever played by someone other than David Gilmour).

The new album is, she says, modeled on the records of the early 1970s, but the most blatant musical reference on Daddy’s Home isn’t Pink Floyd or Steely Dan or any of the names Clark has been dropping in interviews. It is, confoundingly, Sheena Easton, whose first single, ‘9 to 5’, supplies the melody for ‘My Baby Wants a Baby’, about a woman who is very much not the happy homemaker of the Easton song. Oooh, clever reversal. Except it’s not. It was all an accident.

‘I wrote the song, and for 12 to 24 hours I was walking around thinking: “My God, I’ve just written the best melody of all time.” But then I started thinking: “But it’s so familiar. God, it’s like it always existed and then it just poured out of me.” And I was like, oh wait… “My baby takes the morning train…” And I thought: “Oh, this actually works really well — it adds a layer to the song that is very interesting.” I have of course given Florrie Palmer, who wrote that song, her publishing due.’

The 1970s references aren’t just for aesthetic reasons. Clark thinks we’re having our own early 1970s moment, as a veneer of social cooperation is removed. ‘We are in a time that feels very uncertain in a lot of different ways: economically, obviously; we are still in a pandemic; there is cultural uncertainty. And what happens, I think, in human nature is that we want something to hold on to, and if getting perpetuated and pushed to the top is this idea of moral certainty that social media can help legislate, then that’s what people are going to cling to. I’m interested in ideas that can cause less human suffering, rather than more. Hopefully that’s not a controversial take. But I’m not interested in moral purity. I don’t know what that looks like: it seems like a lot of times when we’re on the hunt for it, there end up being far more casualties. Who among us… — I end up sounding like Jesus — let that person cast the first stone.’

None of that sounds remotely controversial, of course, but the careful phrasing suggests that Clark knows a large number of her admirers are precisely the kinds of people who do see outrage in every deviation from acceptable thought. I suggest to her that we probably both see ourselves on the liberal left, and that it gets a little wearing to see our own side demand constant orthodoxy of thought, even if we agree with most of the orthodoxies.

Our conversation had begun with a discussion of Stalin — Clark has spent lockdown reading about Stalinist Russia, just because she realized she knew very little about it — and she returns to it in her answer, as if a parallel has just occurred to her (albeit without the millions of deaths, the dictatorship, the purges, the pogroms and all that stuff). ‘I think life is incredibly complicated. People are really complicated. The structures of power are really complicated. And we have to be able to talk about the complication and the nuance in order to actually have progress. I am absolutely 100 percent there for progress. It seems to me: look what happened in Russia. When you demand allegiance to an orthodoxy, you create suspicion, bad faith, and people get ahead by pointing at other people and saying: “Burn that witch!” That doesn’t end well. We just need to be thoughtful. We need to be able to listen. We need to be able to talk to ideas, and in the economy of ideas separate the good ones from the bad ones. We need to look at things with logic. We can’t be slaves to the “likes” that the outrage will garner. But I’ll say this and probably be canceled for it.’

There’s a curious theme that keeps cropping up with Clark: physical discomfort. I interviewed her for her last album, Masseduction, and she noted that when she toured with David Byrne she didn’t feel satisfied unless she ended each show bruised. I asked why, and she replied that she didn’t know. In an interview to promote Daddy’s Home she said she had deliberately worn clothing on her Masseduction tour that caused her discomfort. Why? ‘Probably just some conflation of pain and good work. If I can do all this, if I can juggle while my feet are on fire, doesn’t that make the juggling all the more impressive?’ She pauses. ‘I don’t know. I think I wanted to feel in my body, and I wanted there to be an obstacle to feeling in my body while I was performing.’ She pauses again. ‘I don’t know. I’m not really entirely sure.’

Does the notion of discomfort appeal to her at some level? After all, one might say her performances cause discomfort to the audience, not least in — to return to a word she had used — their air of being ‘pervy’. Again she pauses, for a long time. ‘I guess I can never presume to know how people feel or necessarily draw a straight line between what I am doing and how they are going to react. I think I kind of go a bit on instinct, whether things that I think are on that line of funny/surreal/uncomfortable…I don’t know, manic, ecstatic…I feel like we’re all exploring it together at the same time. I’m not sure. I wasn’t conscious of wanting to be uncomfortable when I made myself go up in five-inch heels and do a show for an hour and a half. I just knew how I wanted it to look. I guess when I say “it”, I mean me. Which I guess is a really strangely dissociative way to look at it.’

I’m not entirely convinced. Everything Clark does is so deliberate, so carefully considered, why wouldn’t her approach to discomfort also be a conscious choice? It seems unlikely to be accidental. Her attraction to unease extends to her dealings with the press: at the start of the promotional cycle for Masseduction, she gave interviews in which questions she deemed boring were responded to with prerecorded messages; the other week she demanded an interview — a pretty innocuous one, in truth — be pulled for some unspecified reason, which prompted journalists in Facebook groups to come forward with their own stories of how uncomfortable she had made them feel when they sat down with her (I have interviewed her twice and never felt discomfort, but as an editor, I did once send a writer to meet her who came back quite disturbed by the experience). I suspect — I don’t know, and it’s not a hill I wish to die on — that Clark’s great subject is power itself. It just happens not to emerge in her songs as often as it does in other areas of her professional life.

But why should that be a surprise? It’s exactly what you’d expect from someone as confounding as Annie Clark.

Daddy’s Home is out now on Concord Records. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.