George Orwell once proposed that the specimen literary career takes the form of a parabola in which the downward curve is implied in the upward. You can see immediately how this theory might work with a major-league titan such as Thackeray (promising early sketches leading to Vanity Fair, then downhill to the trackless waste of The Virginians) or James Joyce (peaks in the early stretches of Ulysses before descending to the dream language of Finnegans Wake). But how does it apply to the 71-year-old former enfant terrible and, to borrow another useful French phrase, one-time jeune premier of English fiction, Martin Amis?

A brief sift through the evidence — the two dozen items listed on Inside Story’s ‘by the same author’ page — suggests that, rather than resembling a parabola or even an isosceles triangle, Mart’s trajectory is, in fact, a dead-ringer for a toothpick: vertiginous early ascent and short-lived plateauing out, followed by a long, slow slide whose preliminary signs could be glimpsed all of three decades ago. Which is to say that while there are some fine things in London Fields (1989) and The Information (1995), neither of them is a patch on Money (1984).

The same rule applies to the nonfiction. Yes, Visiting Mrs Nabokov (1993) and The War Against Cliché (2001) have their moments, but experienced Mart-fanciers will probably want to take their stand on The Moronic Inferno, published halfway through Reagan’s second term with a title abstracted from Saul Bellow.

When and why did the rot set in? One conspicuous warning sign was the very early stage at which Mart began, so to speak, feeding off himself. Just as the Beatles advertised their late-period decadence by way of ballads about John and Yoko or hinting that the Walrus was Paul, so Mart’s fiction swiftly reduced itself to self-aggrandizing performance — an ancient postmodernist’s trick, of course, but in Mart’s case rendered yet more problematic by sheer repetitive doggedness. As ‘Bookworm’, the chief literary critic at the British satirical magazine Private Eye once put it, at the end of every novel, as the fire died down and the smoke rose from the creative battlefield, what remained in the reader’s mind was neither plot, theme or treatment but the spectacle of the writer writing.

Or sometimes not even that. To establish Mart against the backdrop of the London literary world in which he took his bow (the 1970s) and in which he performed to such singular advantage (the 1980s) is to appreciate just how much more there was to it than the books themselves. There was, for example, the pull of novelistic heritage (he was Kingsley’s son, and Elizabeth Jane Howard’s stepson). There was the net of association, so widely flung as to include Philip Larkin (godfather), Christopher Hitchens (bosom friend and work colleague) and such sparkling coevals as Salman (Rushdie), Ian (McEwan) and Julian (Barnes). But above all there was the well-nigh unprecedented crucible in which these top-of-the-range literary reputations of the 1980s tended to be forged. As Mart notes at an early stage in the current proceedings, his first four novels (1973-1981) were a couple of hundred pages long and each took 18 months to write, whereas Money, the ground-breaking fifth, was an altogether fatter, finer and better-remunerated proposition.

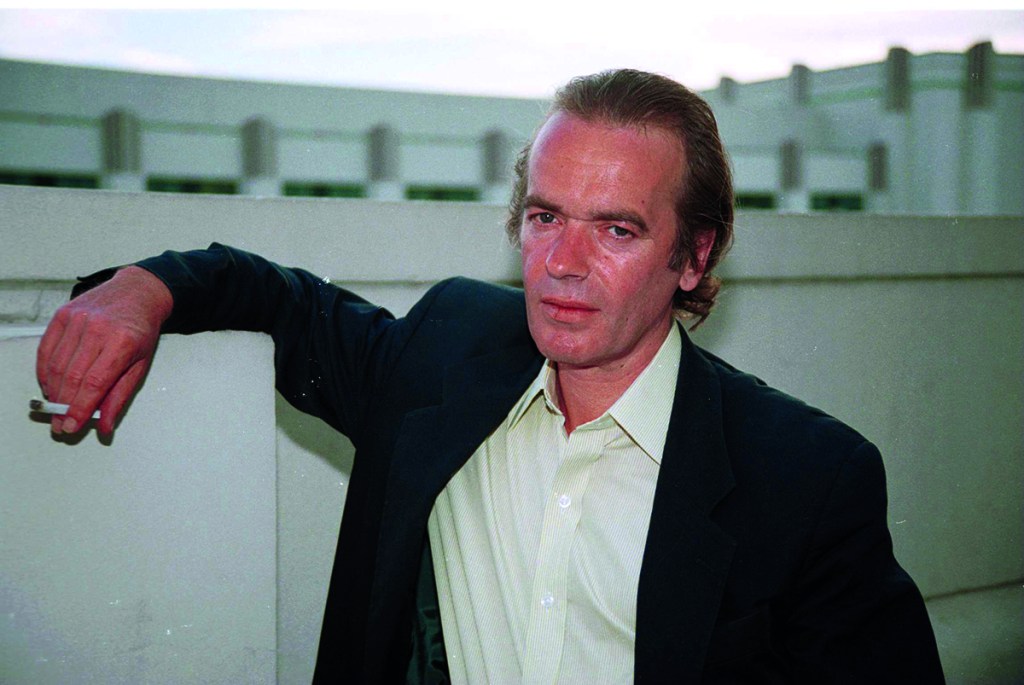

Why, exactly? Well, the era of Mrs Thatcher was a good time to be a writer in England. Transatlantic takeovers and merger-mania meant that, for once, money had begun to flow into an industry hitherto marked by chronic underfunding. Publishers’ advances went through the roof. Book trade publicity, previously a somewhat diffident affair of fiction round-ups, ‘paperbacks to purchase’ columns and modest profiles of serious-looking middle-aged men in spectacles, suddenly exploded into a riot of three-page interviews and ‘Best of British Young Novelists’ promotions. Books, formerly the lame-duck also-ran in a race led by film and music, were suddenly trendy. And no one, in this cavalcade of fame, lucre and media omnipresence, was trendier than young Mart, with his Jagger-ish mien and his ever-changing roster of elegant lady companions.

Quite a lot of this is gestured at in Inside Story, which like many an ‘autobiographical novel’ written by a man in his early seventies can’t help having an elegiac or even a threnodic side. As one who has read practically everything our man has written — an obsession that began 40 years ago in Blackwell’s bookshop in Oxford — I am here to tell you that it is by far his oddest book, as much a curiosity in its way as that jaunty vade mecum from the dawn of video game age, Invasion of the Space Invaders (1978). Part of the oddity lies in some of the procedural obfuscations — more about this in a minute — but a much larger part rests on the sense of déjà vu, the feeling that the man who wrote it is in grave danger of turning into his own tribute act. This is particularly evident in the some of the proleptic footnotes (‘There’ll be more to say about Updike and Henry James’) and also in the many mock-sententious foreshadowings (‘My life was about to change, and as profoundly as a young life can ever change’).

Here, spread over 500-plus pages, along with a lavish index, is a whole heap of reportage from life on Planet Amis. Some of it extends back to the earliest days back home in Swansea with father Kingsley and mother Hilary. Much more of it focuses on dead friends and mentors (Larkin, Hitchens, Bellow). Certain of the names have been changed (Mart’s brother Philip appears as ‘Nicholas’, his late sister Sally as ‘Myfanwy’, various girlfriends seem to have been amalgamated) and the book’s British publisher is billing it as ‘an autobiographical novel that leaves fans trying to draw out the truth from the fiction.’ On the other hand, this particular fan (sort of), who has had the additional advantage of reading Richard Bradford’s 2011 biography, was simply aware of how much of which he (a) already knew, or (b) had come across in print before.

To particularize, most of the reflections on 9/11 can be tracked back to The Second Plane (2008). The memories of Larkin are scattered around his autobiographical writings, although their current iteration has a good deal more to say about Larkin’s crypto-fascist father. Even the snarky reminiscences of one of his father’s old friends, the now forgotten novelist John Braine, ultimately derive from a New Statesman profile from the 1970s, already reprinted in Visiting Mrs Nabokov. Newer material includes Hitchens’s death from cancer of the esophagus in 2011 and Bellow’s long, Alzheimer-cushioned twilight — each of these bits demonstrating just what Mart can still do when he tries — the whole interspersed with some not terribly illuminating reflections on How to Write and the scent that arises from Great Works of Literature.

What is Mart up to here in these re-recordings of his greatest hits, these delicate repositionings and reconfigurings (see the attribution of his post-9/11 intolerance to the influence of the Hitch) and these sagacious remarks about the literary art, some of which look decidedly off-the-pace (to give only one example, note his remarks on the superannuation of the experimental novel, which most critics would say has been making a comeback in recent years)? By chance, I am writing this piece on the weekend that the now-traditional Mart publicity machine cranked into gear in the London Sunday Times (‘Martin Amis teases readers that Larkin was his father’). At hand lies what, in any consideration of Mart and his oeuvre, is a rather significant document: a ‘fiction symposium’ convened all of 42 years ago by a long deceased literary magazine called the New Review.

Here Mart, then a youthful 28 and with his third novel Success just out, can be found insisting that if he tries very hard, he can ‘imagine a novel that is as tricksy, as alienated and as writerly as those of, say, Robbe-Grillet, while also providing the staid satisfactions of pace, plot and humor with which we associate, say, Jane Austen’. Money and London Fields and several of the short stories collected in Heavy Water (1999) were dazzling exercises in this welding together of two outwardly dissociated traditions. Does Mart write like this anymore? Did the Rolling Stones ever really cut it after Mick Taylor left? Reader, ask yourself.

There are interesting parallels with Sir Angus Wilson (1913-91), who, coincidentally, was stopped dead in his tracks by a devastating review of his penultimate novel, As If By Magic, that the 23-year-old Mart contributed to the New Statesman back in 1973. Like Mart, Sir Angus had carried all before him as a spirited youngster. Also like Mart, who quit London for Brooklyn back in 2012, Wilson abandoned his native land (in his case for the south of France) on the grounds that he was under-appreciated. But what really connects Wilson the author of Setting the World on Fire (1980) and Amis the author of Inside Story is a sense of writers who have somehow lost touch with the things that are worth writing about.

Sir Angus, who had made his name with rheumy-eyed reportage from the English social scene, aspired to write ‘world novels’ in a style for which he had little aptitude. Mart, whose early books relied on minute inspections of the urban milieux through which he sauntered, retreated to a spiritual eyrie somewhere in the mid-Atlantic. Significantly, his last ‘English’ novel, 2011’s Lionel Asbo, though intermittently funny, was full of basic errors about contemporary British life.

There is no real remedy for this. Writers always like to ‘develop’, whatever that means, and what animates them at 30 is unlikely to animate them four decades later. All the same, you sometimes wish that Mart would establish himself on a farm in Sussex and write a novel about a small boy and his pet calf. Whatever its merits, it would make a nice change from the umpteenth recapitulation of how Kingsley Amis left his wife and what a wonderful time everyone had working on the New Statesman back in the days of the second Harold Wilson government.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.