Getting there was penitential. The coach from my home in Bad Ischl, Austria, to Salzburg stopped a hundred times, to let on women in dirndls carrying shopping baskets. The train to Munich was subject to delays, messing up subsequent connections. The S-Bahn linking Ostbahnhof with a place called Pasing suffered a derailment, so I had to struggle backwards to the Hauptbahnhof, only to discover my alternative train to Murnau was canceled, then reinstated on a distant platform, resulting in mass confusion. (The Germans are bewildered very easily when things stop going to plan.) At Murnau there was a long wait for the two-carriage shunter service to Unterammergau, outside Oberammergau, where it was by now pitch dark and pouring with rain.

I dragged my suitcase through the puddles and the blackness to find the rented apartment — there were further adventures finding the key, hidden under a neighbor’s plant pot. There were no provisions in the property, nothing to welcome guests, save a single teabag. I could have murdered a drink, but bars and restaurants had long since closed. There’d been no refreshments available on any of the trains. It was eleven wearying hours since I’d left the house. My diabetes was playing up. As Spike Milligan used to say in moments of duress, “Jesus had it easy.”

I kept this in mind the following day, when I sat through the Passion Play, the famous and lengthy reenactment of “the suffering, death and resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” which the municipality of Oberammergau has been staging each and every decade since 1633, to mark deliverance from the plague. Ironically, the 2020 production was scrapped because of Covid, but everything is back to normal this summer, when half a million visitors are expected to turn up — many of them, it seems, American retirees on a bus tour.

Celebrity guests in the past have included William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies, David Lloyd George, one or two czars and Habsburg monarchs, and Mad King Ludwig, who presented the Apostles with silver spoons, except Judas, who was given a tin one.

The statistics are impressive. The Passion Play is an entirely amateur operation, with 2,000 locals participating in full costume, including 550 children. The theater, constructed from six iron arches and a wooden saddle roof, holds 4,200 seats. The stage part is in the open air, with the emerald pyramids of the Bavarian mountains as a permanent backdrop, all pines and moss.

My seat was so far back the curvature of the Earth was involved. But I did get a sense of the panoramic scale of the thing, especially when Jesus entered Jerusalem on a real donkey and hundreds of people waved palm fronds. There was certainly no shortage of extras or what used to be called supernumeraries, babes in arms, spear-carriers, roadsweepers, agricultural sorts looking after chickens, goats and sheep. When Herod came on, he had two camels, each with a cross Kenneth Williams face. A Henry Irving Shakespeare play at the Lyceum during the Victorian era must have been similar — roaring, baying mobs, contributing to the action. And what a fickle lot crowds are — one minute hailing Jesus, calling out to him as King of the Jews and creating what Pilate calls “great upheaval in the city,” the next happy to clamor for Jesus’ crucifixion and the release of Barabbas.

The script at Oberammergau, edited and revised down the centuries, is based on an original text by Othmar Weis (1769-1843) and Joseph Alois Daisenberger (1799-1883). The music, too, pastiche Mendelssohn to my ear, though “expanded” recently by Markus Zwink, was composed a long time ago, between 1811 and 1820, by Rochus Dedler.

What we witness, therefore, in two three-hour chunks (though it seems longer), is “a synthesis of festival, folk drama and worship.” It is highly conservative, amounting to a sort of living museum piece, excruciatingly dull and reverent at times — and not just because it is delivered in a monotonous, droning German. Though there is a nominal director (since 1990, Christian Stückl), everything has to be ratified by an elected Passion Committee, which only started giving townswomen a say in 1984 — and until 1989, married women and women over the age of thirty-five were not allowed to appear on stage in any role. There were resignations and court cases when the rule was changed. Another eccentric edict bans false beards and wigs; males cast in the show have to grow their own facial hair.

Perhaps my seat was too far away, but I thought everyone looked the same. The disciples couldn’t be told apart. Even more confusingly, I mistook Judas for Jesus for the first few hours — each is given to long, declamatory speeches. When whoever it was said, “Blessed are the peacemakers,” I immediately started chuckling, remembering “Blessed are the cheesemakers” in The Life of Brian. Costumes were a drab muchness, also. Muted stone-gray tunics and shawls, dull green robes, everything the palest of ash shades. Was this meant to be realistic? It was as if every effort had been made to shear the story of anything miraculous, spiritual, fantastical — no special effects, halos, angels with wings. Nothing baroque or golden.

Indeed, the Passion Play, as I found it, was a political play, not even a particularly religious one. Jesus was a young agitator, saying, “I have come to proclaim freedom for the captives and liberation for those who are bound.” The authorities don’t appreciate this, pressing to have him silenced. Over and over, the high priests, tribal elders, scholars, scribes and associated retinues — always hundreds of them — pile out of the temple in indignation, marching the full half-mile to center stage, muttering and shaking their fists to indicate anger. “You are overruling the traditions of your ancestors,” Jesus is told. I wish he could have overruled some of the choral interludes — recitatives, arias and mass singing, which padded matters out still further.

There were interminable scenes of theological debate, trials, accusations and counter-accusations — very dry and philosophical, believe me. Nevertheless, I could see why the Passion Play has been controversial. It is unavoidably antisemitic, Jesus’ death brought about by the Jews, who are as fearful about vested interests (“We must put an end to the activities of this teacher of false doctrines”) as of Roman reprisals. Caiaphas, in particular, is like a pantomime villain, hissing and sweeping about, telling his fellow priests: “Do not put everything at risk because of one Galilean.” Jesus “irritates the Romans and thus puts us, the whole city and the temple in danger.” His execution on the cross is simple expedience: “It is better that one person perish than the whole nation.” When Jesus is turned over to the Romans, Pilate, who makes his entrance and exits on horseback, sees through the strategy at once: “You dare to see me as your blind tool that carries out your rulings?”

A rabbi, seeing the Passion Play in 1922, thought the slant of the drama “injurious to peace and goodwill.” In 1949, the American Jewish Committee also complained about the way Jews were shown as Christ-killers — and an Oberammergau spokesman said, “We have a clear conscience. We have to fulfil a vow and there is nothing offensive in our play,” which Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Miller wanted people to boycott. In 1978, Cardinal Ratzinger gave the Passion Play his blessing.

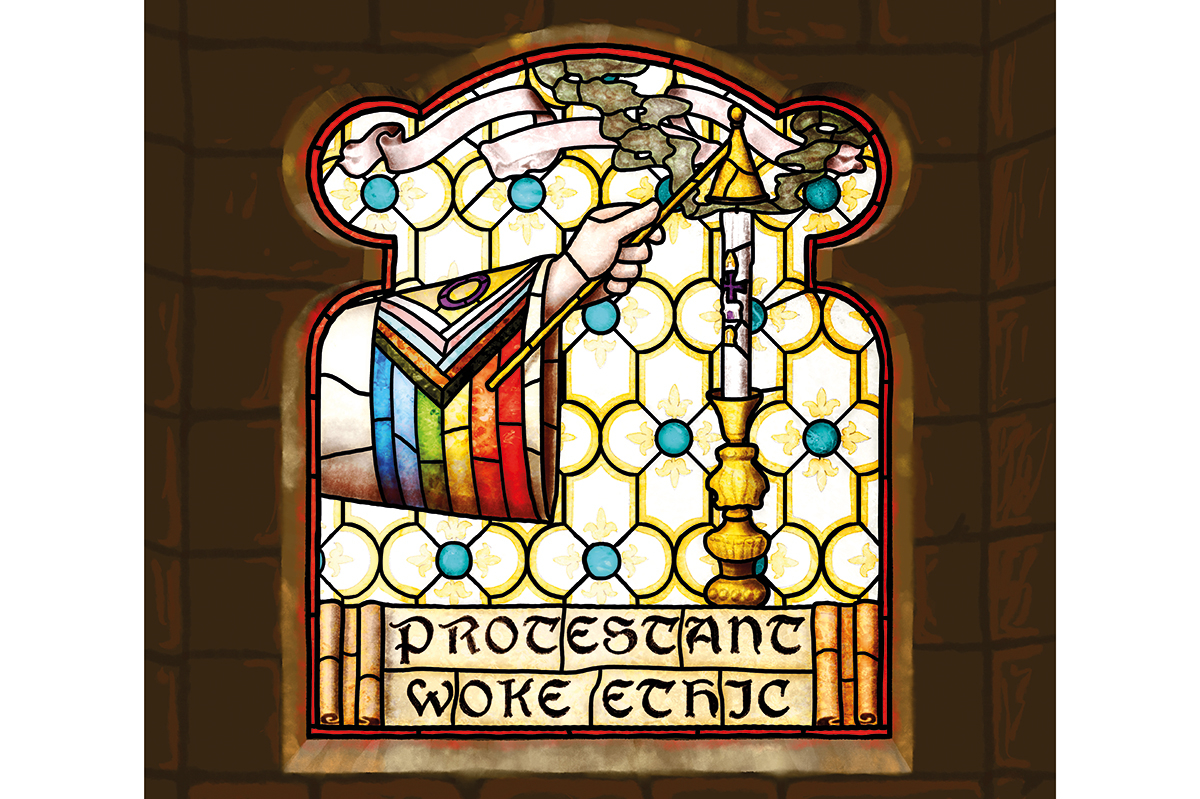

What of the war years? Hitler visited in 1930, thought the show the “origin of the German tradition,” and particularly identified with Pontius Pilate, who was “racially and intellectually superior” and “appears like a rock in the midst of the Jewish dregs and crowds.” The Passion Committee in the Thirties and Forties were all loyal Nazis, insisting the Gospel story be “kept clean” and protected from “foreign elements,” as if they were unaware everything had been written originally in Hebrew. Today, the Passion Play presents a very different Jesus, one who is, according to Stückl, someone who “turns up with a bunch of poor people who really don’t fit in,” a “woke” hippie with his outcasts, the prostitutes and cripples, an antihero who “deliberately irritates,” intent on provoking revolution and turmoil. For Hitler, no doubt, he’d have been less of a climate-change activist, more of a Wagnerian superman, blond and indestructible.

In 2022, Jesus doesn’t ascend to heaven. After a graphic and gruesome crucifixion sequence, he is carried off by the wailing womenfolk. I more or less had to be carried to the adjacent Hotel Alte Post, where in short order I spent 103 euros on emergency food and drink, particularly Marillenschnaps. The waitress was a gigantic Heidi with plaits. The man running the hotel turned out to be Pontius Pilate. A tourist asked if I’d been in the show, “possibly as Lazarus, you mean?” I said, as I was by now pale and wan. My journey home the next morning was again protracted. Though Hitler went twice, I shan’t, even though Oberammergau is a pretty place, doing a brisk trade in Christmas ornaments in June. Down the road is the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang castle, Neuschwanstein. I’d like to see that.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.