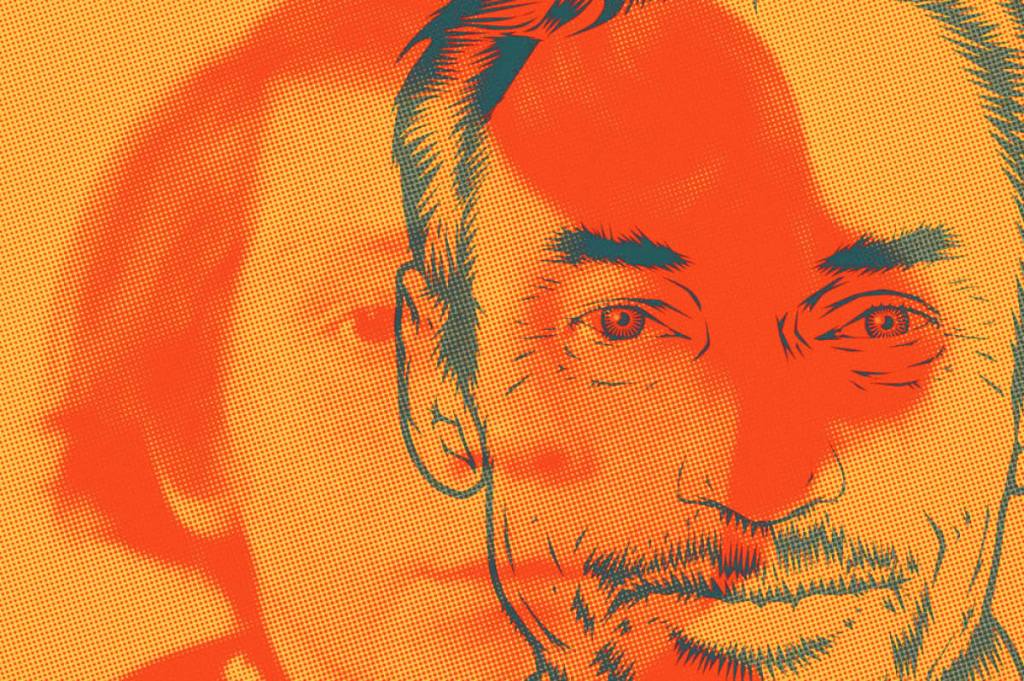

It’s just after nine on a gray Pacific Northwest morning, and Danny Bonaduce, the once winsome redheaded child star of TV’s The Partridge Family, is dispensing life advice on Seattle’s 102.5 KZOK classic-rock radio station. “My ex-husband has a gambling problem and won’t ever show up for our two kids,” one distressed young woman announces.

“Keep a journal. Write down what he does wrong, it’ll be useful one day in court,” says Danny, speaking in his familiar rapid-fire, gravelly voice. “He has to perform if he’s ever going to see the kids. You’re not a bad person, he is. The kids know that. Be strong. Hang tough.”

“My twelve-year-old son is cool,” the next caller says, “but he’s rude to his mom. Should I intervene?”

“Intervene?” says Danny, fairly bristling at the question. “Yes! Drop the hammer on the kid! He’s disrespectful to your wife. Would you take that from anyone else in the world? Jump on this right away. C’mon, man! She’s called your better half for a reason!”

“My six-year-old daughter went to an open-call audition for a movie,” another woman says. “They said they liked her, but that she needs acting lessons which I should pay for. What should I do?”

“Don’t give them a cent,” says Danny. “Never spend money before you’re making money. Absolutely not. It’s a scam. No. Never! Never! Never!” he adds, his voice rising in counterpoint to the station’s theme music.

Danny’s show, with its essential mix of freewheeling wit, Seventies rock cuts and fast-paced gags (Danny’s co-host Danni Sarah has a regular slot entitled “Where Has Sarah’s Beaver Been?”) isn’t exactly Edward R. Murrow. But at least you can say that his life-coach segment is experience-based. Whether it’s the perils of child stardom, booze, drugs or relationship issues, the sixty-four-year-old Bonaduce’s been there and back again. There’s an underlying note of good cheer behind it all, too. “I have the best job in the world, and I live in the best city in the world,” Danny tells me. “Even I couldn’t blow that.”

Danny’s other recent challenge has been his health. He took a timeout from his show in 2022 after he woke up one morning and found he was slurring his words and having trouble keeping his balance. These weren’t entirely unfamiliar problems for the one-time wild child, but it soon became clear that something was seriously amiss. At first Danny thought he’d had a stroke, like his father before him, but after months of tests it turned out that he was suffering from hydrocephalus (water on the brain) likely caused by his taking a blow to the head at some stage in the past. When coming to consider possible culprits for the injury, Danny and his doctors found they were somewhat spoiled for choice.

“Maybe it was the time I was hit in the face by a flying electric guitar,” he speculates, “or when I got punched around by José Canseco during a charity boxing match. There’s no shortage of candidates. Let’s face it, I’ve done a lot of really, really stupid things in my life,” Danny sighs.

After undergoing successful brain surgery this June, he snapped back with a typically robust message on social media. “I lived, bitch,” he tweeted.

In a way it’s surprising that Danny ever found himself in show business in the first place. His mother, Betty, and father, Joe, met on the campus of Temple University in Philadelphia. Joe wrote the occasional TV script, either despite or because of which he held actors in low regard. To him they were cattle, or worse, but in late 1963 he decided to pack up his wife and kids, including four-year-old Danny, and move to Los Angeles purely to sell a screenplay. In later years, the only career advice Joe ever gave his family was, “Remember, acting is one step below pimping.” Even so, young Danny was soon going out on auditions, landing jobs on commercials and a couple of episodes of popular sitcoms such as Bewitched, where he appeared alongside a chimpanzee. In an early lesson about the vagaries of show business, the chimp bit him on the head.

In due course, nine-year-old Danny found himself working on an MGM comedy-drama called The Trouble with Girls. It wasn’t much as far as movies go, but it starred Elvis Presley. “I had to go to the can, and Elvis let me use the one in his personal trailer,” Danny remembers. It was another indelible Hollywood moment. “I couldn’t help but notice that the taps in his sink you pushed open to run the water were gold-plated, and shaped like a woman’s legs. That was different. I like to say that Elvis also gave me a Cadillac when production wrapped, although I should add that it was a pushcart version, all of about five feet long.” Then came The Partridge Family.

It’s not given to every ten-year-old child to earn $400 a week (about $3,000 in today’s terms) starring in a hit sitcom. But there was Danny, going along for the psychedelic-bus ride in a show with the faintly weird premise of a widowed mother of five in a post-Woodstock version of the Von Trapp family. The Partridges, in the show and in real life, toured America’s concert halls, dodging hundreds of screaming fans every time they performed or even showed up at the studio for work.

“I loved being famous,” Danny says. But, this being a morality tale, there was a downside, too. Sometimes those same fans, peering through the windows of the Bonaduces’ car and disappointed at not seeing either of his teen-heartthrob costars David Cassidy or Susan Dey, would turn and shout back to their friends, “Never mind, it’s only Danny.”

Another harsh lesson in Hollywood realities came when Danny and his mother pulled up at the studio gate one morning in July 1974, just as they had five days a week for most of the past four years. But this time, instead of smiling and waving them in, the guard on duty looked at them and said, “Go home — the Partridge Family doesn’t live here anymore.” Danny wasn’t yet fifteen, and he was canceled.

That’s when the fun began, and Danny’s life became a self-destructive rollercoaster ride of sex, drugs and booze, with periodic stops at his latest therapy session. It’s a Hollywood truism that audiences confuse an actor with the character he plays on screen. Danny was playing a version of himself on The Partridge Family, down to sharing the same first name, but where Danny P. was wholesome, Danny B. was already chugging cocktails and smoking pot. The disconnect wasn’t apparent to fans, who simply assumed the two Dannys were interchangeable.

For much of the 1980s, Danny became a sort of celebrity without portfolio. Not having saved a cent of his sitcom fees, he spent some days sleeping in his car, and his nights cadging drinks in and around the VIP rooms of Hollywood clubs, where he was asked “Weren’t you Danny Partridge?” or “How did you get to be such a loser?”

There was a low moment in March 1990, when he found himself in a darkened Florida housing project attempting to do business with someone he assumed was a drug dealer, but who turned out to be an undercover police officer. Then there were more drugs, and a period when he was under treatment for bipolar disorder and sex addiction. “At the time, I was quite proud of that diagnosis,” Danny says.

At his trial for the Florida incident, the judge asked him if he had taken any drugs in the three months since his arrest. Danny looked him square in the eye and said, “No, sir.” The judge gave him a $1,000 fine and community service. “It’s amazing how easy it is to commit perjury when it’s your ass on the line,” Bonaduce reflects.

But it was a high-speed chase through downtown Phoenix, fleeing numerous police cars and a helicopter, where Danny really hit bottom. He’d been out cruising around town, and genially offered a ride to someone he thought was a young female sex worker. It soon transpired he’d made a mistake about his companion’s gender, which is how he wound up brawling in the street with a man in fishnet tights and a miniskirt before screeching off in his souped-up Camaro. Unsurprisingly, he was the punchline of the following night’s monologues on the Carson and Letterman shows.

By this time, Danny was in his early thirties and the poster child for the ranks of American child stars who’d made it big and blown it. But, unusually, there was a second act to his career. In 1991, David Cassidy was embarking on one of his own periodic comeback tours and asked his old Partridge Family buddy to go out and tell jokes as his opening act. “It was a challenge,” Danny admits. “I’d never done stand-up comedy before, at least intentionally, and to make matters worse, David insisted I do it sober.” Nonetheless, soon they were traveling around the country on a bus again, just as they had in the old days.

“David told me I had to stay away from booze, drugs and women,” Danny reflects. “It was a stretch, because those three things pretty well constituted my whole life at the time. But I did it. The other thing he told me was that if I stayed clean, by the end of the tour someone would have offered me a job.” Danny kept up his end of the deal, even if he did relapse on occasion during the next two decades. Cassidy was right about the job, though. Within a few weeks, Danny was acting as the designated wacky sidekick to a DJ in his native Philadelphia, before going on to host his own early morning show in Chicago. He was a natural for radio. It turned out that Danny wasn’t just good at talking, he had the much rarer gift of knowing how to listen. He still liked a good dust-up from time to time, but increasingly he brought his pugilistic skills to the ring in the name of charity. At various times, he traded blows with Donny Osmond and former Brady Bunch star Barry Williams, and later fought retired outfielder Canseco, 100 pounds heavier and nearly a foot taller, to a draw. “He never knocked me down,” Danny adds with unfeigned pride.

Along the way, Danny was twice married and divorced. The second union in particular made the tabloids (“Danny Gets Hitched on First Date!”), but lasted sixteen years and produced two children, Isabella and Dante. His marital counseling and other issues featured as a central component of the 2005-06 VH1 series Breaking Bonaduce, which was either a refreshingly unfiltered reality show, or the epitome of trainwreck TV. It’s a matter of taste.

“All significant milestones in my career,” Danny says, adding that he has now truly found domestic contentment with Amy Railsback, a former substitute teacher turned talent manager, whom he married in a Maui beachfront ceremony in 2010. “I proposed a couple of times, with a skull-and-crossbones ring, and then eventually she accepted,” he says. “I was lost for words. But thrilled. Like beyond thrilled.” It’s characteristic of Danny that the modulation in the machinegun-like rattle of his voice barely changes as he expresses this. “I actually only heard about it when the wedding planner called to speak to Amy, and told me I was getting married. That was the first I knew. I said, ‘Honey, you got something to tell me?’ Then I thought about it and said, ‘This is a great idea!”’

And it was, too. In short order the couple moved to Seattle, where Danny landed his job with KZOK radio. He spent a lot of time at home over lockdown, and the station let him keep broadcasting from a spare room in his house when he began to feel ill in 2022. “Like I say, between having Amy and this job, I’m the luckiest guy in the world,” he repeats. With his continuing recovery from surgery, everything finally seems to be going Danny’s way. About the worst you can say about him these days is that he’s a disappointment for dirt-dishing hacks. He no longer falls out of bars, does coke all night or turns up for work shredded. “Been there, done that,” he says with some finality. “Life is too short.”

When Danny’s old friend David Cassidy died in November 2017 at the age of sixty-seven, his rueful last words were, “So much wasted time.” Coming from a man who had his own share of professional knocks, it was a salutary reminder of the importance of making every day count. It obviously struck a chord with Danny, anyway, because even though his body is already generously covered with images and slogans of various kinds, he found space to have the phrase tattooed directly over his heart.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2023 World edition.