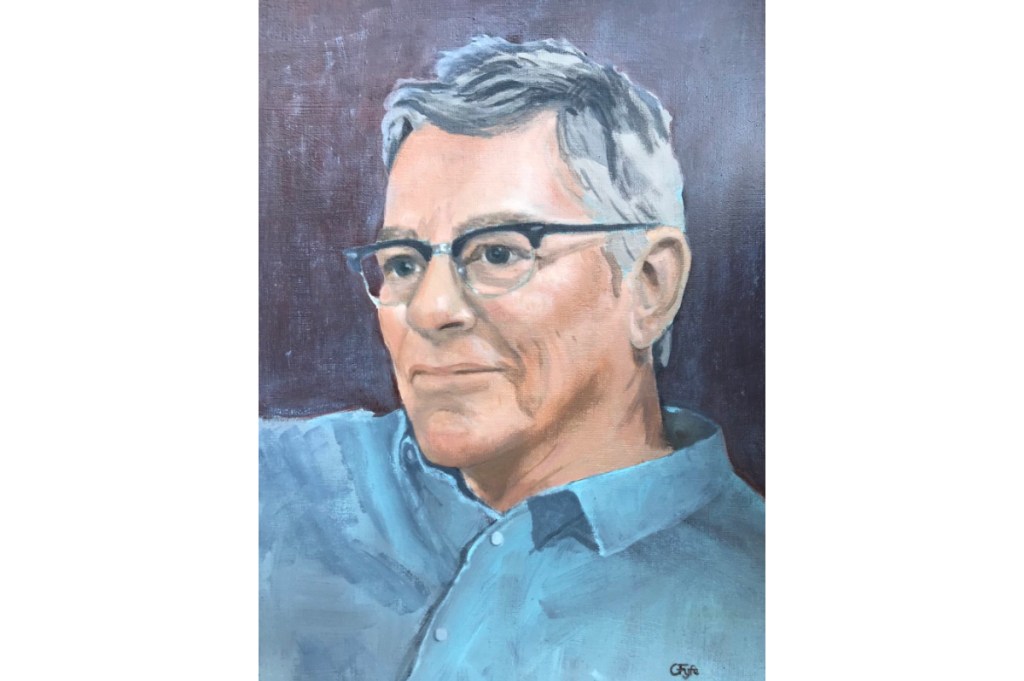

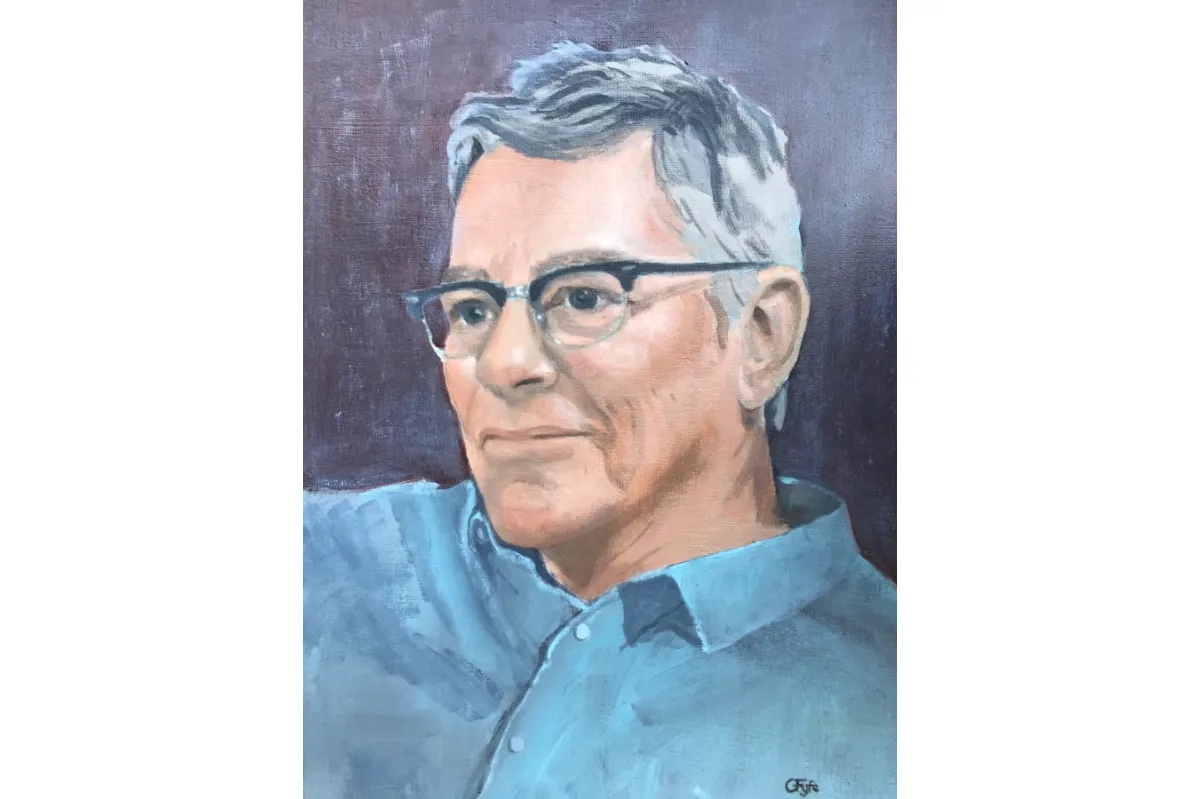

A world without Jeremy Clarke is a glummer place. The author of this magazine’s Low Life column for twenty-three years, who died on Sunday morning, was a spirited writer of the old school. He loved a rollicking good time, a beautifully turned phrase, a good gossip, casting an observant eye over life’s absurdities and England. He despised the hypocrisy of the progressive middle classes, big egos and TV boxsets.

He had quirkily conservative views, but friends of all classes and races, a deep knowledge of an unusual range of subjects, including rural matters, and a cheerful modesty that belied his talent as a writer.

He despised the hypocrisy of the progressive middle classes, big egos and TV boxsets

I played a small part in his becoming a professional writer when I saw a hilarious piece he wrote in a London student magazine about a trip to Africa and gave him his first regular writing job as the Modern Manners columnist for Prospect magazine in 1995. That led to a column in the Independent on Sunday, and in 2000 he was pinched by Stuart Reid, deputy to Boris Johnson at The Spectator, to write Low Life, after the death of Jeffrey Bernard. (Sweetly, he always felt guilty about leaving me for the brighter lights of the Spec.) But, along with travel writing in the Telegraph, and later the Mail, and pieces in the Sunday Times, he briefly achieved his dream of earning a comfortable living as a writer.

It was a dream that began in the library of Jeremy’s sixth-form college in Southend. He had always been a bright boy with a love of words but neither Benfleet primary school nor his grammar school near Epping had inspired him academically. But that evening in the library a favorite English teacher, a raffish ex-journalist, happened to be standing behind him as he was surveying the books. The teacher plucked out a volume and said to Jeremy: “Read this.” It was Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall. And so began a lifelong love of Waugh and English satirical fiction and a determination to become a writer.

Just a few weeks ago, as he lay on his bed in the upstairs room of his home in Cotignac, looking out on to the blue skies of Provence and the Massif des Maures mountains, he returned to Waugh, watching YouTube videos of his literary mentor interviewed by Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Their clipped upper-class accents contrasted with his own Essex twang and, as he always insisted, lower-middle-class upbringing. His father John was a bank clerk turned sales rep and heavy drinker; his mother Audrey, with whom he always remained close, a nurse and devout Christian.

After Jeremy was seduced, aged seventeen, by Waugh’s silky, sardonic prose, he adopted a kind of restless double life that lasted a couple of decades. He took odd jobs often inspired by the literature he was reading — factory jobs (Steinbeck), assistant in a mental hospital (Kesey). His affable manner helped him fit in everywhere, but he rarely let on that he went home after his shift to immerse himself in literary novels, lest he be considered soft.

In the early 1980s his mother moved him, plus sister Vivien and brother Jim, to Devon, where she opened an elder care home in Strete. He began a psychiatric nurse training course but was thrown out for bad behavior — he was not the settling kind either in jobs or relationships. “The truth is, Dave, for much of my life I’ve been a drunk and a bum,” he would say with a smirk. Actually, he belonged to that select English tribe: the reactionary bohemian.

In the West Country he worked as a binman for several years in Salcombe, the most fashionable of Devon seaside towns, bought and sold a house, notched up two convictions for drink driving and one for possession of amphetamine sulphate, became a father to Mark after a one-night reunion with Sarah, a much younger ex, and not long after that disappeared to the Democratic Republic of Congo on a four-month tour. He was inspired to go to Africa by a patient in Audrey’s care home and by reading Eugene Marais, the polymath, naturalist and morphine junkie (something Jeremy was condemned to echo in the final months of his life).

Africa was a revelation in many ways, most importantly because he discovered he was just as clever and much better-read than the graduates on the trip, so was inspired to go to university. “I came back altered and made a conscious decision to join the bourgeoisie,” he wrote.

He first had to acquire some A-levels, having left school with just two O-levels, and having done so applied to read English at Waugh’s old Oxford college, Hertford. Foolishly, they turned him down, so instead, he went to SOAS to study African history. He spent much of the time attending English lectures at nearby UCL, where he was spotted by Karl Miller, head of the English department, after he read a review by Jeremy of a book on ferret husbandry. Through Miller’s contacts, notably the then literary agent Alexandra Pringle, Jeremy was briefly touted as the next big thing and even secured a £50,000 advance for a book. He spent a chunk of the advance and never wrote the book.

For several months he knew that the game was up and he faced his end with fortitude and cheerfulness

But from the mid-1990s he did have his Prospect column as a showcase, often featuring eccentric characters from Audrey’s care home, which led to the Spectator column and regular travel writing. They were mainly happy, if chaotic, years for the football hooligan aesthete from Leigh-on-Sea. He eschewed being a wage slave or a traditional parent and lived much of the time with his mother in Devon, helping around the care home.

He could thus focus on drinking, drugs, sex, following West Ham United, travel and, most important of all, honing his writing skills. He had a darker, self-destructive streak too. Extreme drunkenness, a long on-off relationship that caused him much pain, a car accident that may have been a half-hearted attempt to kill himself. And maybe, underneath it all, a self-doubt that might account for the slender Clarke literary legacy. However, his failure to ever write a proper novel probably has as much to do with his writer’s perfectionism. Even before his health deteriorated, it would take him two days to write his Low Life column.

Eventually the wanderer found a happy anchor to his existence with the love of his life, Catriona Olding. They first met at a Spectator party in 2011. Jeremy had announced in one of his columns that he would offer free tickets to the publication party — for a book collection of his columns — to the ten people who came up with the worst-taste jokes. Catriona was one of the winners and came down from Scotland, where she lived with her sculptor husband and three daughters. They hit it off but remained just friends for several years, exchanging occasional emails about books and poetry and jokes.

Then Catriona’s marriage disintegrated and the way was open for them to fall stupidly in love. It wasn’t quite that simple. Catriona was spending most of her time in Cotignac, in the Var region of Provence, in a house built into the rust-colored rock that looms over the pretty village once famous for its silkworms and now for quinces. Jeremy was still in Devon, among other things helping to look after his two beloved grandsons, Oscar and Klynton.

They managed to spend about half their lives together at this time, mainly in France, but just as the gods had sent Jeremy settled contentment with Catriona, they also went and spoiled it by chucking in prostate cancer too (first diagnosed in 2013). The cancer retreated for a few years, which must have been the best of his life, in that bucolic Provençal setting, with many local friends and visitors, his column, lots of drinking, and Catriona, who was painting, cooking, caring, managing property and chattering with him about their shared love of books.

At the end of 2019, Audrey died and he moved to France full-time. He slipped in just before new post-Brexit rules came in (he was a proud Brexit voter) and the Covid shutters came down. The cancer spread, and with it an extended entanglement with the mainly generous French medical system, as Low Life readers know well.

For several months he knew that the game was up and he faced his end with fortitude and cheerfulness. By chance I was staying close by for several weeks in March and April, and was able to share laughter and reminiscences even as the pain and indignities of his illness bore down on him and Catriona. Luckily for Jeremy she is an ex-nurse.

His columns, while always bathed in a kind of noble lightness, began to reflect his loss of hope. I was, oddly, lying next to him on his bed when I received an email from The Spectator asking me, in the light of his writing more explicitly about his imminent end, to write this tribute. I thought the better of telling Jeremy, but he would have seen the funny side.

He was just recovering from staggering back from the Cotignac town hall, where he and Catriona had tied the knot in a civil marriage. It was one of the last times he left the house and soon after he was restricted to his bed. My partner Kate baked a wedding cake with the West Ham crossed hammers symbol for Jeremy and a mini painting of the Provence countryside for Catriona.

He was religious in a quiet way, inherited from Audrey, and had the Book of Common Prayer by his bedside. He welcomed visits from the local nuns on more than one occasion, though the final time they came he did admit that he was not sure he believed in God. He gave his heart to Jesus for a couple of years at SOAS, and was even celibate for a while, but the relationship was never going to last.

Still curious and intellectually lively in the shadow of death, he immersed himself in the literature, diaries and music of World War One. He sent me a note saying he was listening to George Butterworth’s “Banks of Green Willow” and had discovered that when Butterworth was killed at the Somme, his commanding officer had not known he was one of the most promising composers of his generation.

Jeremy — or Clarice as he was known to his school and West Ham mates — was a modest man and appreciated modesty in others. He seemed genuinely surprised, when he started writing about his illness, how many devotees of the Low Life cult there were. People wrote to him in their droves (including a minor royal).

One of the last big chuckles I was glad to provide him with was recalling one of my biggest boobs as editor of Prospect magazine. Paul Barker, the former editor of New Society, had written a piece with the phrase “Books do furnish a room.” Not, at the time, knowing this was a reference to a novel by Anthony Powell, I thought it was a slip of the pen and excised the redundant “do.” Barker was furious. Jeremy, a Powell fan, and class-conscious to the end, thought it comical that someone with my expensive education could commit such a howler.

Books certainly did furnish Jeremy’s rooms, great tottering piles of them everywhere. He even liked to smell them. Farewell Jeremy, you lovable English eccentric, and I do forgive you for leaving me for the higher calling (and better parties) of The Spectator.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.