You will find Bacon’s Castle amid the flat tobacco and peanut fields in Surry County, Virginia, across the James River from Jamestown, if not quite a “castle” then certainly a very fine Jacobean mansion and the oldest brick dwelling in America. When I first visited this part of the Tidewater in 1958, I was ten and Jamestown, the year before, had turned 350. Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip came to crown the anniversary, and replicas of the three ships that brought the first English here in 1607 — Susan Constant, Godspeed and Discovery — were tied up in perpetuity at Jamestown. I came on a field trip with my schoolmates to take in the sights and something of the history of the place and of Colonial Williamsburg, just up the road. Bacon’s Castle was not on our itinerary.

Back in those bad old days of the 1950s before the Civil Rights revolution and with segregation still largely intact, Virginia schoolchildren compulsorily learned the commonwealth’s history from textbooks loaded with what would be considered today all manner of pernicious stereotypes. Our texts were mildly Confederate, skated over the evils of the Peculiar Institution and attributed the cause of the Civil War less to slavery than to northern aggression. They were frankly paternalist in tone, though in those uncertain early years following the Brown decision they attempted not to be discourteous toward Virginia’s black citizens. “Colored” was out; “Negro” was in. Both whites and blacks were taught from the same books, though they were taught apart.

This was in some contrast to the attack-dog attitude of the 1619 Project and its ilk, which shamelessly employ history for a contemporary civic purpose (“anti-racism”). Virginia: History, Government, Geography, the text I remember from 1957, used the past for its own civic purposes — not least resistance to forced integration — but did so in a manner that was positively genteel by comparison. Preposterous as it now sounds, our texts instilled the belief that our history was suffused with a certain “Virginia spirit.” Though never closely defined, this had something to do with nobility of character, moderation in politics and general good manners. As one of those (white) schoolboys, I can attest that the civic purposes of history, however high-minded, held little allure compared with the pretty girl in the next row, the ballgame after school or the need for memorizing facts as presented in order to do well on the six-weeks test and make your parents proud. It was a different age.

But there is something else to note about these self-celebrating, long-since superannuated texts in connection with Bacon’s Castle. When we are very young, first contact with history in just about any form, whatever its sins of omission or outright errors, opens our time horizon outward beyond short and shallow personal experience. So with the explorers in the great age of discovery: first contact with the American surprise opened their space horizon outward beyond the known European world. Whatever we learned or mis-learned back in the Fifties about slavery and other subjects of consuming present concern, Virginia history did something for which I am still grateful. It inducted us into a tradition. We learned that this plot of ground — called “Virginia” after England’s unmarried Queen Elizabeth, and originally plotted on the map as far as the Pacific Ocean — was a stage set for high drama. It opened with the Jamestown landing in 1607, which as we were taught dutifully to recite made Virginia “the first permanent English-speaking colony in the New World,” the oldest of the thirteen colonies and the states that became the United States. We moved on to the meeting in 1619 of the House of Burgesses, the first representative assembly in North America; and to the landing, also in 1619, from the privateer White Lion of twenty-some shackled Africans with all the suffering and sadness that arrangement foreshadowed. Always, meritorious great men (meritorious by their deeds if imperfect in their characters) played the leads and were presented as idols for our emulation: George Washington in war and peace; Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration; James Madison and the Constitution; John Marshall and the Supreme Court; Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. A notch or two down the list was Nathaniel Bacon, whose surname attaches to the “castle” across the James that I visited at last, last summer.

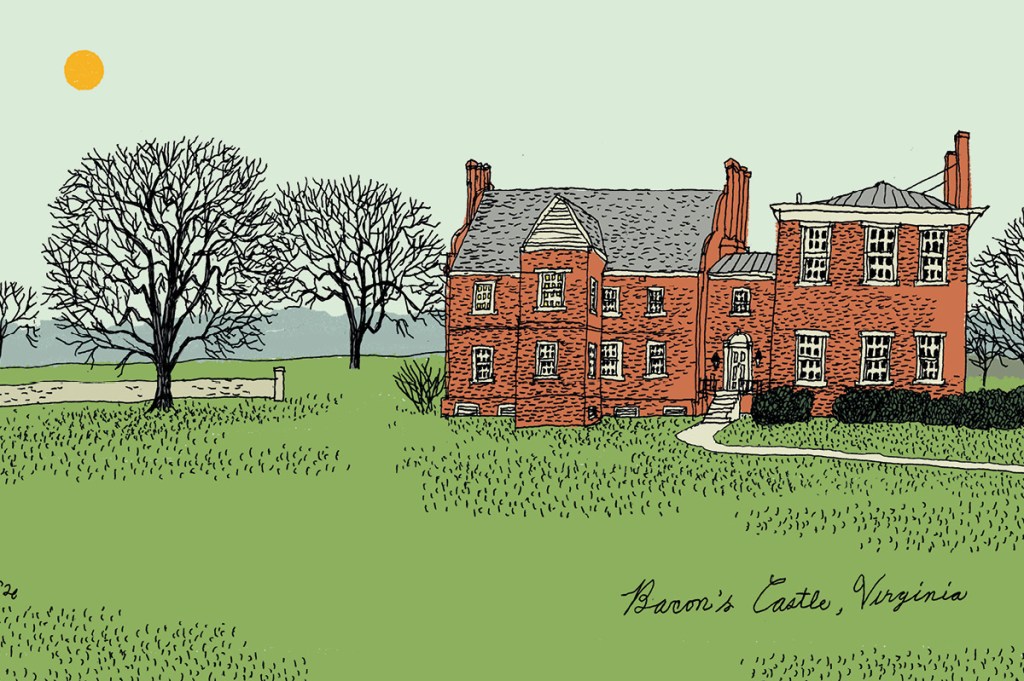

It is one of only three surviving Jacobean houses in the Western Hemisphere. The other two are in Barbados. It is owned and operated by Preservation Virginia, formerly and more richly named the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. Compared with Jamestown and Colonial Williamsburg, it is remote, little known and lightly visited. These are reasons enough to take the time to take the ferry across the James to Scotland (Virginia) and spend a couple of hours there. (It is not open every day and it’s best to call ahead.) It was built by Arthur Allen, a rich planter-merchant, in 1665 and passed down by inheritance through extended family until the 1840s. The record is silent as to why Allen built such a house. Perhaps he was just a rich man showing off his success. Perhaps he was an admirer of English cultural ideals (he sent his son to England for schooling) at a time when there was much in that culture to admire. Whatever his reason, perhaps both, we can be grateful for the result. Subsequent owners (there were only three: the Hankins, the Whites and the Warrens) lived there until 1973, when the APVA bought the castle and surrounding forty acres. No Bacons ever lived there, but Bacon’s Rebellion, a short-lived revolt of planters against the policies of colonial governor William Berkeley, which happened hereabouts in 1676 and which was led by Nathaniel Bacon, has left its name on Allen’s great brick house.

A distant kinsman of Sir Francis Bacon and cousin-by-marriage of Governor Berkeley, a Cambridge MA who read law at Gray’s Inn, Nathaniel Bacon came to Virginia in 1674 and settled at Curles’s Neck, a large plantation upriver from Jamestown. Berkeley had high hopes for the young arrival and welcomed him onto the Governor’s Council. Soon, however, Bacon found himself embroiled in the protest of planters unhappy with Berkeley’s Indian policy. The subsequent armed revolt, which Bacon led, turned into a tangled fracas between two overlarge egos and resulted in the burning of Jamestown, the retreat of the governor to the Eastern Shore and the dispatch from England of a thousand troops to restore order. As the rebellion fizzled, Berkeley brought to trial and hanged all its leaders he could put his hands on, prompting King Charles II to remark, “That old fool has hanged more men in that naked country than I did for the murder of my father.” But not the young rebel Bacon, who died of fever in the fall of 1676 in Gloucester County and was secretly buried, no one knows where. In his two years in Virginia, he probably never came anywhere near Arthur Allen’s house, though an on-the-run group of his followers took refuge there for a time, ransacking it for the silver which they did not find. Their sojourn was enough, however, to fix the association in popular memory.

It is a fine structure, impressive in size though crude in some of its workmanship. Its bond brickwork gives a passable imitation of English masonry techniques of the time but has about it a certain homemade quality. That it survives at all is even more surprising given the inhospitableness of the location. Rainfall is heavy in the Tidewater, humidity stifling, the water table high and a challenge to foundations. On first approach down a long avenue of trees, one is struck with a vision of a slightly off-kilter manor house with striking triple-stack chimneys turned at forty-five degrees rising from the gable ends, and by a strange scar where the front entrance used to be. (In the nineteenth century it was moved to the hyphen connecting to a Greek Revival service addition on the east side.) There are four levels of living space: a dirt-floored cellar, two main living floors and a garret level under the steep slate roof. Much of the post-and-beam timber framing is original, though termite damage has necessitated repair and reinforcement over the years. The first windows, English cross-mullioned casements with leaded glass, have not survived and were replaced with double-hung sashes. The interior as restored represents rooms at different periods — the predominant plaster plainness of the seventeenth century, the more elaborate painted paneling and greater emphasis on privacy of the eighteenth — which docents lightly interpret with stories of the occupants over 300 years, mixed with anecdotes about the castle’s current-day restoration and stabilization. Few other historic American interiors have been so elaborately researched (there were seven inventories between 1711 and 1871), which has reduced the need for conjecture typical in less-documented house museums. The furniture and textiles that furnish it now tell us with a high degree of confidence what it looked like then.

Even so, or perhaps for that reason, what Bacon’s Castle looks like inside and out has about it the undeniable strangeness of the past. By American standards the house is ancient. It seems better to belong in England’s Surry than Virginia’s, an illusion that may have been just what Arthur Allen intended. Its architectural aspirations obviously exceeded the skills of its provincial builders. Allen was no doubt the richest of any of its owners, and its slow but inexorable deterioration until restoration began in the 1980s is a testament to the relative poverty of successive caretakers and the forlorn mood of the surrounding country. And its association with Bacon’s Rebellion and the brash English aristocrat, dead at twenty-nine, who never set foot in it, has not faded away. A striking stained-glass likeness of Bacon, every inch the cavalier, was commissioned by APVA in 1900 and long displayed in the Powder Magazine at Williamsburg. It can now be seen, tastefully backlit, in the Greek Revival appendage just opposite the cash register.

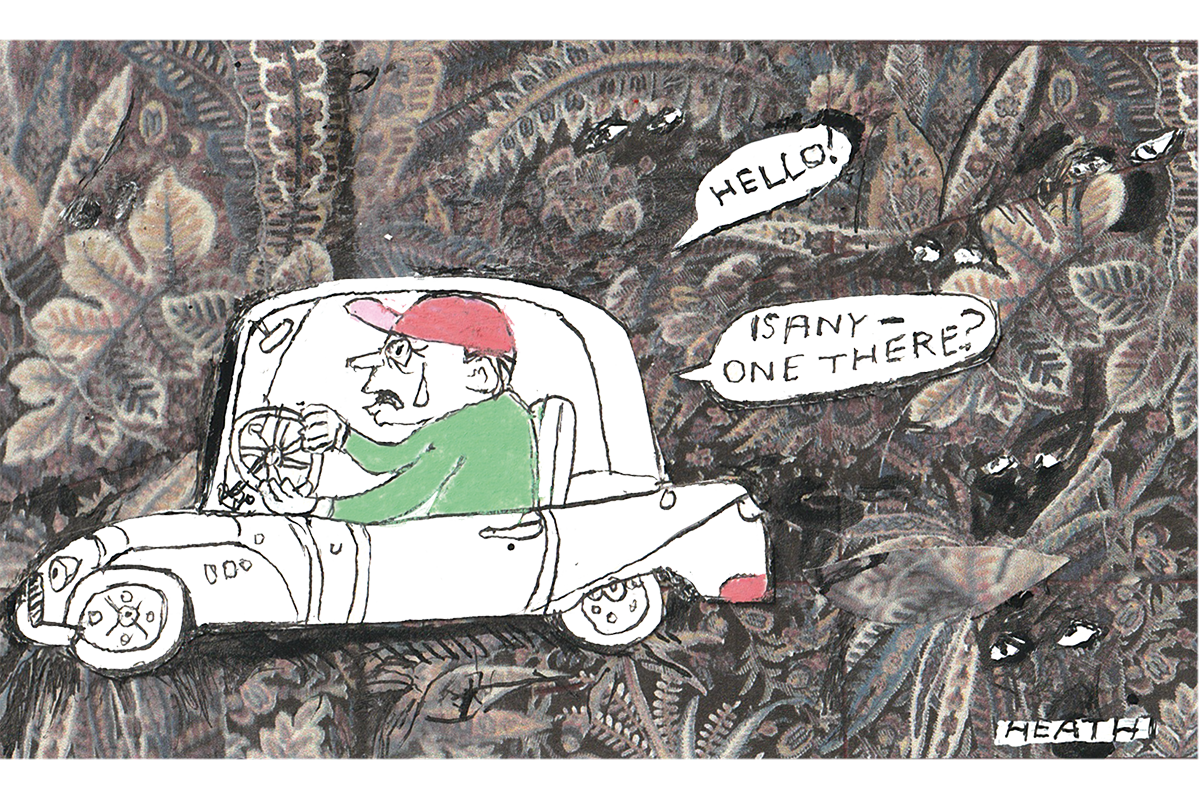

Finish your tour of the interior and then walk quietly around the soft sandy grounds which include the remains of the earliest English formal garden in America, and be left, as I was left, with that “What’s this really about, anyway?” question. Those Virginia history textbooks from childhood patriotically taught us Bacon belonged with history’s heroes. He captained the first stirring of revolt by freedom-loving Virginians against arbitrary royal authority, in a precursor to the American Revolution a century later. Modern interpretation tells it differently: that his “rebellion” was more a flash-in-the-pan flare-up over Indian policy that exposed the conflicting interests of those who lived near the frontier and Governor Berkeley’s self-serving councilors in Jamestown. Historical interpretation is a matter of words and slides about with intellectual fashions. Whichever version of the story you pick, the tale of Bacon’s Rebellion also left its name on something altogether more solid and needless of any further interpretation: Arthur Allen’s strangely beautiful Jacobean house in the fields of Tidewater Virginia, so improbable in both its origins and its survival. It is a reminder of the truth, soaked up in Virginia history class sixty years ago, that history is a large place, far distant from and foreign to our puny present experience. It is why, still a student, I walk back into it whenever I can, as I can at Bacon’s Castle.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply