Hello, shipmates! Digby here, back ashore, back at my desk, bunking in Vermont for the holidays with a shapely ski bunny and a seabag stuffed full of sailing stories of harrowing feats on the high seas. Well, few of them are particularly harrowing, save for a midsummer horror when a bespectacled crewmate, his face fogged with mask mist, misplaced a pair of Pol Roger bottles that now sleep with the fishes.

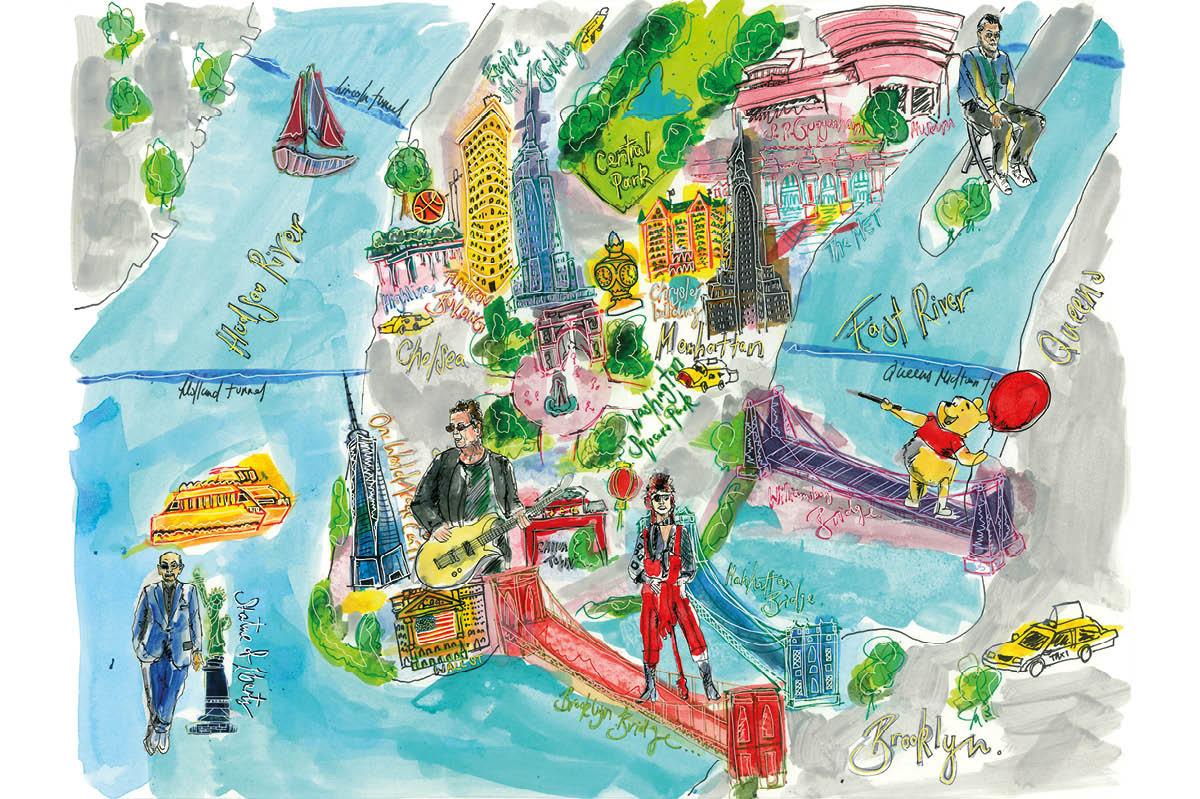

Champagne donated to Davy Jones aside, it’s been a good year. I spent the summer in Newport, of course. It’s a fine town, and though I feared it would feel a bit dead on account of the persistent plague, the pandemic was no match for the nautically minded. Instead of the solicitous, even enthusiastic response to restriction I’d seen in Manhattan and Connecticut, we happy few sailors found a keen camaraderie in casting off the draconian diktat of the state. Free sail, free labor, free men as they say.

I was in Newport in no small part to avoid the once and future ex-Mrs. Dent. Yes, dear reader, I’m afraid to report that the rift has not mended. Mother remains squarely on my wife’s side of the matter. There will be more frost than usual on New Year’s Day when the Dents gather for the customary sherry.

Now, Newport is unlike most American towns. You have the native Newporters and the seasonals, of course. But that simple separation disguises a litany of distinctions. Wilder said there were ten Newports — I count six.

Among the permanent residents, there’s still a seedbed of the flinty New England fishing village, the sort of spot you can sail into up and down the seaboard to meet taciturn and toiling locals. Then you have the resort townies, indolent and perennially intoxicated; their chief offseason occupation seems to be stealing bicycles. Next you have the husks of families of faded fortune, folks who insist they’re still seasonals even though they haven’t left in years and sold the manse ages ago.

The summering set is a mixed bag, comprised of old colonial families, Gilded Age hangovers and later-vintage fortunes. Much of its notorious snobbery having gone by the way, it’s a permeable circle so long as one does not try to join during the summer or in Newport. Its apertures are elsewhere in time and space — at school, on campus and in various places of employment.

The other two groups — the celebrities and the weekenders — treat Newport as they would any resort. Hoi polloi show up for the festivals, the weather, the crass Kennedy nostalgia and the drinking. The mega-rich come to escape the world, retreating into their hideous piles, architectural abominations almost without exception.

Summer in Newport: to be among my people, all of us in our native habitat. Flying the spinnaker, battling around the cans and then zigzagging back across the bay. We all know each other or know somebody who does.

And so it was that, early in the summer, I bumped into Susan Wiley (née Wallace), the ex-wife of a school classmate, Tim Wiley, at a yacht club get-together. We fell into spending the summer the way single people in the back half of middle age do. I doubt Timmy was terribly troubled. He ran off with an art student three years ago and, as I heard ad nauseam, has been gallivanting all around the world.

Tall, thin, and ethereal, Susan’s still a striking woman even if her looks have slipped somewhat from Carly Simon to Jimmy Stokley. Expectations were limited, hers and mine. Still, I did my part and listened to her complain about Timmy, a man I think of as perennially seventeen — and whose existence had not troubled my mind more than once a decade in the intervening years.

The whole business was surreal. But still, I’m grateful for all of it. By the time you’re reading this we’ll be skiing the deep and crisp and even in Vermont. Manhattan will be open again, and even Mother may have thawed. We’ll all of us have returned to the rituals of our lives, to the places and people that make us feel fully ourselves. Happy New Year!

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2021 World edition.