It would be tough for any country to lose 7-0 in a World Cup qualifier, but when the losing team is China, and the thrashing is at the hands of arch-rival Japan, it is deeply humiliating. The defeat was “shameful,” according to an editorial last week in the Global Times, a state-controlled tabloid, while the Shanghai-based Oriental Sports Daily called it “disastrous,” adding: “When the taste of bitterness reaches its extreme, all that is left is numbness.” Some commentators called for the men’s team to be disbanded, bemoaning that a country of 1.4 billion people could not find eleven men capable of winning a match.

While being awful on the field, it seems some Chinese players are world champions at wrongdoing

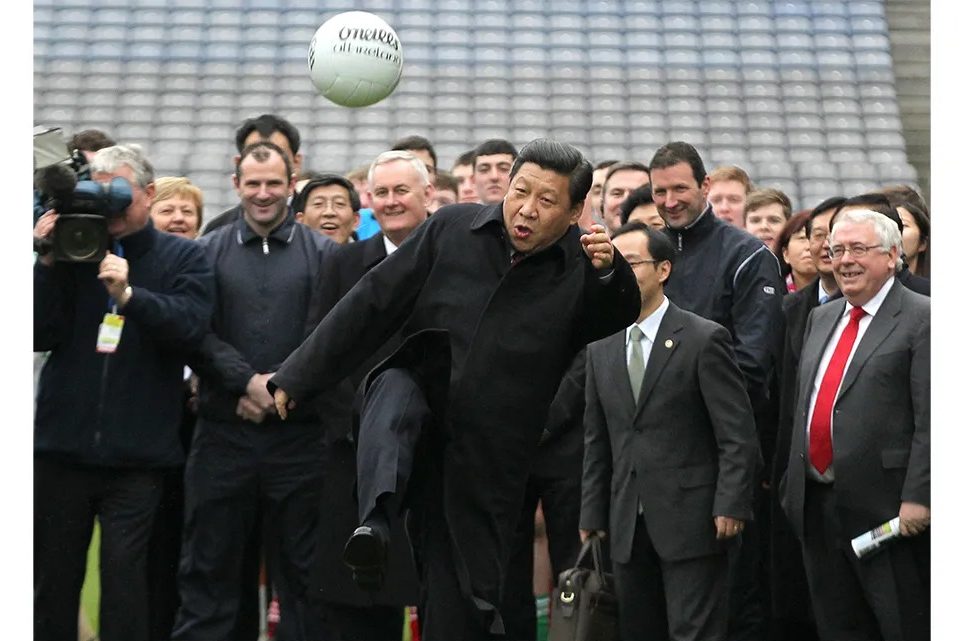

It is almost a decade since Xi Jinping, China’s supposedly soccer-mad president, launched a multi-billion dollar national crusade to turn the country into a soccer superpower. While China lhad forged ahead economically, the ultimate symbol of soft power remained a western stronghold, and that grip needed to be broken if China was to realize Xi’s “China Dream” of becoming a truly great power. Ten years ago, China was ranked eighty-first in the world by FIFA, the sport’s governing body, just ahead of Sudan and Iraq. It now ranks eighty-seventh. Xi’s masterplan has been a colossal failure, on and off the field.

His vision was spelt out in “The Overall Chinese Soccer Reform and Development Program,” published in 2015 with all the pizzazz of a state plan for steel, coal or pork production. The short-term goal was to create a “soccer management model with Chinese characteristics.” In the middle-term, the men’s team was to become the best in Asia before scaling “the highest global ranks.”

The main tools were to be party diktat and cash — lots of cash. All schools were to include soccer in their physical education curricula, and the number of schools with soccer fields was to rise from 5,000 to 70,000 by 2020. The target was to have 50 million people, including 30 million students, playing soccer within ten years. Soccer was also to be at the center of a broader “national fitness strategy,” which earmarked billions of yuan for the construction of public sports facilities.

There was even a target for “per capita area of sports fields” — 19 square feet per person. The strategy was closely linked to the burgeoning cult around Xi, portrayed on state media as a soccer-mad man of the people, often kicking balls around and watching youth games. Thousands of coaches were trained and Chinese companies were urged to support the national effort to reach soccer greatness. Nominally private companies, well attuned to the needs of the party, sank billions of dollars into the country’s top teams, splashing out on players and facilities. They went on a spending spree abroad, bringing in foreign players on contracts worth up to $40 million a year. In 2016, Italy’s World Cup-winning coach Marcello Lippi was appointed head coach of China’s national men’s soccer team on a reported salary of $28 million a year, second only to Manchester United’s then coach José Mourinho. According to FIFA, Chinese clubs spent $1.7 billion on international transfers between 2011 and 2020. A Chinese consortium bought a £350 million stake in City Football Group, which owns Manchester City. Other Chinese investors once controlled Southampton, West Bromwich Albion, Aston Villa, Birmingham and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Chinese buyers snapped up stakes in Italy’s AC Milan and Inter Milan, looking to tap into their marketing and coaching expertise. Evergrande, the now bankrupt property giant, announced plans to build the world’s biggest soccer stadium in Guangzhou — “a new world-class landmark comparable to the Sydney Opera House and Burj Khalifa in Dubai, and an important symbol of Chinese soccer to the world,” it boasted. The sheer volume of money was astonishing — as was the corruption, even by the standards of the Chinese Communist Party. While being awful on the field, it seems that some Chinese soccer players and officials are world champions at wrongdoing. Last week, forty-three of them, including three former internationals, were banned for life following an investigation by the Chinese Football Association (CFA) into match fixing and gambling. The ban followed a clear-out at the top of the CFA, including the jailing for life of its president and an eleven-year sentence for his vice-president for bribery.

Why has Xi’s soccer-scheme been such a failure when a rigid top-down approach has helped China succeed in the Olympics? China uses an intensive and disciplined bureaucratic system modeled on the Soviet Union, scouting for children at an early age and plucking them out for full-time training at elite government-run sports schools. It’s a method which relies on rigid routine and repetition, meaning it excels in individual, not team-based, sport. In essence it is a machine with the single purpose of turning out other machines to win medals. Soccer doesn’t work like that. As a team sport, it requires creativity and innovation; authoritarianism seems almost guaranteed to destroy it. Soccer is an open and free-flowing game of countless permutations, relying on the brain as much as, if not more than, physique. “Playing soccer is very simple but playing simple soccer is the hardest thing there is,” Dutch soccer legend Johan Cruyff once said. “You play soccer with your head and your legs are there to help you.”

Caixin, a Chinese business magazine, has bravely pointed out that the CCP’s grand soccer plan was overseen by rapacious bureaucrats with no real interest in the game, whose plunder thrived in the absence of any independent oversight. Soccer is, in other words, a metaphor for CCP rule, and the stifling way Xi is micro-managing China’s economy and society. The fiasco laid bare by the defeat to Japan and the rampant corruption should contain lessons for Xi’s even grander plan to create an innovation economy by diktat and wads of cash, but there is little sign that any of them have been learned.

Ian Williams’s Vampire State: The Rise and Fall of the Chinese Economy is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.