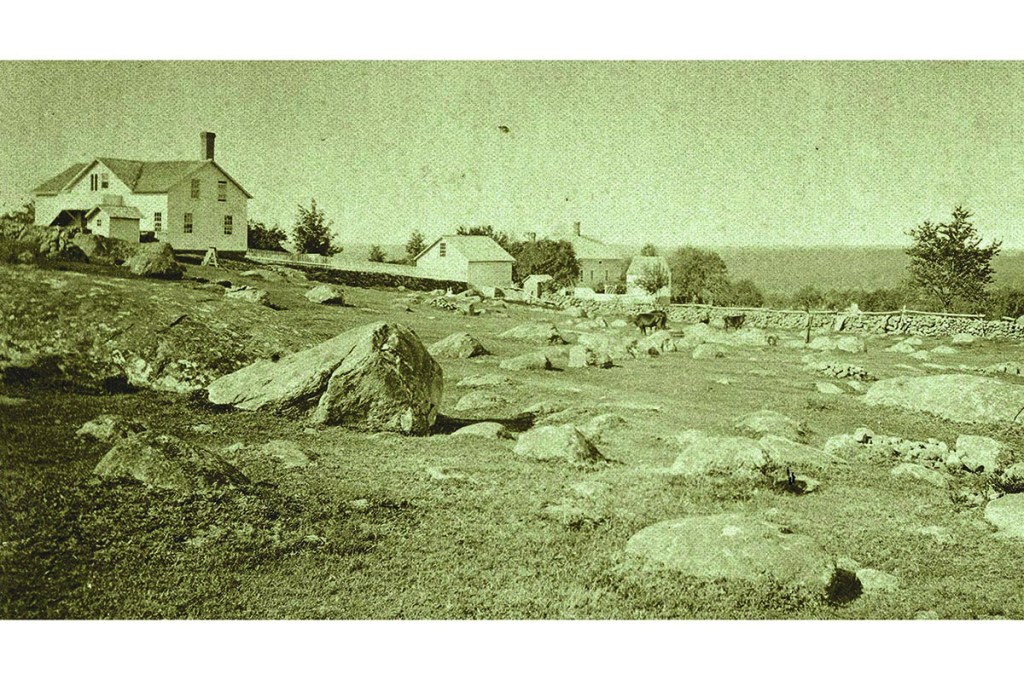

Brightman Hill lies deep in the forests of Hopkinton, Rhode Island. It is named for the Brightmans, one of the families who farmed it, and evidence of its agricultural past is, to most observers, unambiguous: old building foundations, a nineteenth-century burial ground, an extensive network of stone walls and hundreds of stone heaps, the results of field clearing. But in 2019, a federally-funded survey of Brightman Hill shattered these traditional interpretations.

The surveyors, Ceremonial Landscapes Research, LLC, are a small group of antiquarians led by Alexandra Martin, a registered professional archaeologist who recently earned her doctorate in anthropology. Instead of stone heaps and walls, the surveyors reported “linear stone groupings” on Brightman Hill. One, they said, “brings to mind a turtle.” Another “appears to have the head of a snake”; another contains “a ‘nest,’ large enough for an individual to sit in.” Boulders, naturally milled and deposited by glacial ice, came alive. One was categorized as “an apparent effigy of a human head,” significantly facing southwest, while the flat section of another became a “stone seat” from which celestial alignments could be observed.

This is not satire. This is academic archaeology gone woke. New Englanders may not realize it, but the ground is moving beneath their feet.

Stone heaps, walls and other ruined stone structures are scattered across the secondary forests of New England. Traditionally, archaeologists agreed that they were vestiges of abandoned farmsteads, reclaimed by the forests when many farmers left for the cities or pastures new. But now the culture wars have come to this previously polite field.

Today, radical left-wing academics support claims that the stones are the ruins of ancient Native American ceremonial constructions, and that they need protection from ongoing “settler-colonial” development. Tribal officials champion this claim, presumably to further their own campaigns for “decolonization.” Their “resistance” is applauded by attention-seeking antiquarians and a public entranced by guilt and ideas of social justice. I call this confluence the Ceremonial Stone Landscape Movement (or CSLM).

CSLM claims are fashionable, and almost uniquely powerful. None of these stone structures were signed and dated by their creators, but ceremonial claims carry particular weight — especially when anyone who dismisses them risks being accused of continuing the destruction of Native American culture. Yet the movement’s roots are neither ancient nor grounded in Native American tradition. They’re not even that deep.

The movement and its bizarre theory originated in the late twentieth century among a group of white, middle-class antiquarians. Many are members of the New England Antiquities Research Association (NEARA), founded in 1964; at the time NEARA’s founders resented academic archaeologists for refusing to take seriously their theory that New England’s farmstead ruins are in fact the remains of a megalithic culture transplanted by settlers from Europe in prehistoric times. By 1984, one NEARA member detected a “persecuted-crusader” complex among its members, who seemed determined to “wave the banner of truth with regards to the ‘real’ prehistory of New England” until the “mainstreamers… fall in line and admit the visions of a minority were accurate after all.”

The same year, James W. Mavor, Jr. and Byron Dix of NEARA flipped the script. In Manitou: The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization, they replaced the baseless notion that pre-Columbian Europeans had created the region’s ubiquitous stonework with a more modish but not much more plausible theory. The rubble, Mavor and Dix claimed, was the physical remains of a hitherto unrecognized Native American civilization that had been deeply preoccupied with ceremonial practices.

Their suite of assumptions has now matured into the precepts of Ceremonial Stone Landscape Theory. These hold that most of the dry-laid stonework in New England’s contemporary forests is in fact astronomically-oriented ritual landscape architecture; that it was constructed by precolonial Native Americans; that much of it survived colonial-era landscape “abuses” under the covert protection of Native Americans and white sympathizers; and that today these truths are evident only to perceptive individuals who reject mainstream history and archaeology.

Manitou offered a fresh research trajectory for the antiquarians and an indictment of the professional archaeologists. It also offered a completely new history of New England — so new, in fact, that the Native Americans of New England seem not to have known about it. The antiquarians pursued Manitou’s vision through the 1990s, but they didn’t gain political traction until a group including NEARA members met with tribal representatives in 2003 to convince them that much of the region’s stonework had been created by their ancestors. This twenty-first century conquest of indigenous ideology by settler-colonists proved wildly successful.

Later that year, the intertribal congress known as the United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. acknowledged a “sacred landscape,” purportedly long hidden from public awareness, encompassing eight Massachusetts towns in the suburbs and exurbs of Boston. Two years later, in 2005, this alliance of tribal officials and renegade antiquarians went to war with archaeology, now condemned as settler-colonial statecraft, and its enablers in settler-colonial government.

Carlisle, Massachusetts, one of the eight towns in the “sacred landscape,” had spent $2 million on a forty-five-acre lot. The municipal authority planned to build affordable housing, a sports field and an environmental reserve on it — until representatives of the Narragansett Indian Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) informed the town that the stone piles and walls on the site were part of a “sacred ceremonial complex” that should be listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

“We are constrained by Tribal tradition from offering public detailing of the practices at such sites,” wrote tribal representatives. “But in general terms, this complex was used by our region’s medicine people and tribal women for ceremonies relating to the maintenance of balance and harmony with the spirit realm, with our Creator, with the spirit of our Mother the Earth and the healing energies of her springs and fresh flowing waters.”

Alan Leveillee, an archaeologist from the Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc., examined the Carlisle site and reported finding “at least one flake that indicates that stone tool making took place in that area.” In 1997, Leveillee had inspected similar stone piles and walls on a plot behind Carlisle’s town hall and concluded that there could “be little doubt that Euro-Americans were the agents of the landscape features we recognize within the project area today. The existing walls have their origins in specifically Euro-American agrarian practices.” This time, however, he refrained from giving an opinion.

The municipality accepted the tribal position and preserved the stonework in perpetuity. The implications were profound. Tribal officials now had a new type of claim that could be applied to almost any stony property. They had also, perhaps unwittingly, unlocked a new synergy. Before the Carlisle case, someone who dismissed the antiquarians’ ideas could be accused of closed-mindedness. After it, they could be accused of racism. White antiquarians had become the proxy bearers of Native Americans’ moral authority as a historically oppressed class.

Most of New England’s stone heaps were generated by nineteenth-century farmers. Antiquarians who insist there is no documentary record simply haven’t done their homework. Several accounts exist in period agricultural journals and newspapers. For instance, the Providence Journal in 1895:

On the Josiah Dyke place, in this region, are a number of curious heaps of stones, piled up without mortar into pyramids so well and so solidly built that although built 60 years ago they are still in as good condition as ever, except where mischievous boys have torn them down. They were placed there over half a century ago by an uncle of the owners of the property. He was demented and spent his whole time in the fields, which are full of stones of all sizes, picking up the stones and placing them with great care in heaps which tapered slightly and reached a height of six feet or more.

Other accounts, such as this one from New York’s Putnam County Courier in 1873, record that children were often given the task of heaping stones:

How well I remember, writes an ex-farmer, those warm, relaxing spring days on the old farm when I was just large enough “to pick up stones.” What tedious, dull back-aching, hand rasping, boy-disheartening days those were! But I do not remember what force it gave us boys when we were told in the morning, “Boys, pick up a dozen good, large heaps of stone and then go a fishing for the rest of the day!”

Archaeological investigation of stone-heap sites throughout New England strongly supports their association with historic agriculture. Unsurprisingly, stone heaps in Connecticut and Rhode Island have been found to contain pieces of nineteenth-century farm trash. However, once CSL Theory crossed the threshold of racial laundering, it spread freely. Professional archaeologists were wary of opposing the Native Americans’ claims, so there was little pushback.

CSL Theory has penetrated the municipal plans of Hopkinton and Smithfield, R.I., and Massachusetts institutions including the Conservation Commission of Carlisle, the Town of Wayland, the Upton Historical Commission, the Hopkinton Area Land Trust and the Historical Commission of the Town of Wendell. In 2018, the latter even signed a memorandum of understanding with the tribal historic preservation offices of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, the Mohegan Tribe, the Narragansett Indian Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) “to identify and protect ceremonial stone landscapes within the town’s jurisdiction.” CSL-themed articles have appeared in multiple peer-reviewed journals of archaeology and anthropology.

Within a decade, tribal endorsement has pulled this once-fringe theory into the Overton window of academic respectability and municipal policy. Meanwhile, rural landowners, most of whom are white, have acquired a powerful weapon against developers: they can contest development by calling in antiquarians and tribal officials to declare the existence of a ceremonial stone landscape, thereby transubstantiating their personal agenda into an indigenous social-justice mission. Other religious groups have lent a hand. The Syncretic Spiritualists of the Northeast have indigenous and non-indigenous members. They too revere “ceremonial stonework” and have claimed that they may fall ill and even die if their access to it is denied.

Most striking of all has been the response of archaeologists. A silent majority simply avoids the topic as a political third rail, but others have engineered an envelope of legitimacy around it. These highly educated minds seem to agree that any tribal claim should be taken as a self-evident truth. This has the effect of broad-brushing skeptical colleagues as racially insensitive, if not bigoted. Dr Craig Cipolla, currently a curator of North American archaeology at the Royal Ontario Museum, suggests contract archaeologists are seeking “comfort” when they attribute stone remains to “white farming practices,” and calls their disregard of Native American interests a “purification” that prepares the land for development.

In a presentation on the Archaeological Institute of America’s website, federally-employed archaeologist Dr. Laurie Rush plugs Manitou as recommended reading and claims that “identification of aboriginal stone features as farmers’ piles and root cellars” advances the “disenfranchisement of Native Americans.” Contract archaeologists Charity Moore and Matthew Weiss renounce the terms “cairn” and “chamber” due to their “disrespectful, racist, or imperialistic undertones.” Dr. Curtiss Hoffman accuses the Massachusetts Historical Commission of committing “scientism” against Native Americans when it fails to take Ceremonial Stone Landscape claims seriously. Former Rhode Island state archaeologist Dr. Paul Robinson calls skeptics “redneck archaeologists.”

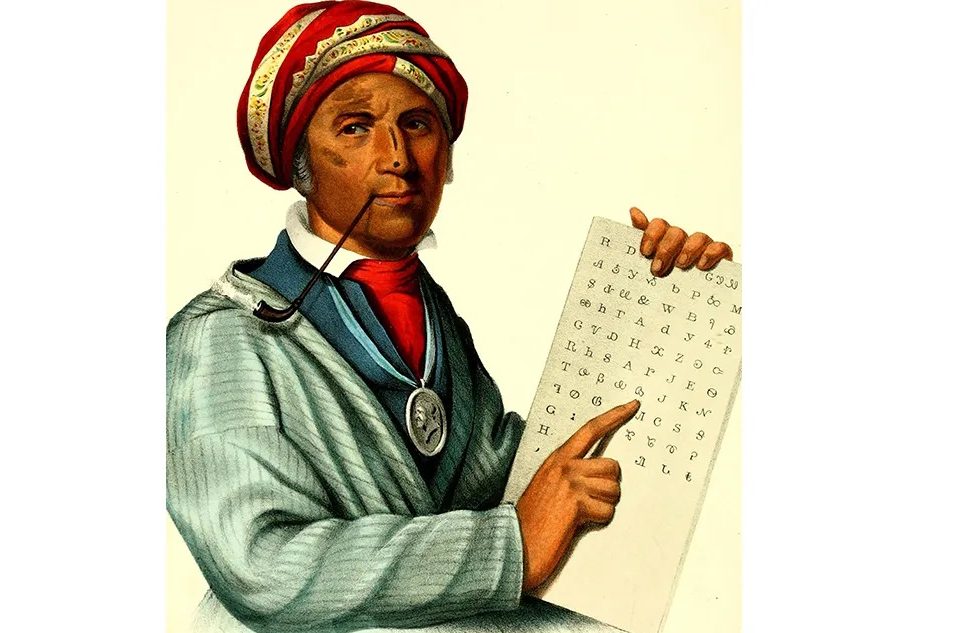

Lloyd Wilcox, the late Chief Medicine Man of the Narrangansett Indian Tribe, has been cast by some as the movement’s patron saint. Yet in 2008, Wilcox explained that his people scarcely built anything out of stone until English colonists taught them stonemasonry. His testimony, transcribed below, is featured in a documentary on Narragansett stonemasonry:

One thing you should understand, the Narragansetts, precolonial Narragansetts, to my knowledge, did not build stone walls. Why would people — the Woodland Indians — where everything was wood and bark and cloth and squash and corn and fish and game? Unless they were building a fish trap in a very small stream or something along those lines, there would be no need. The trade was learned, not the handling of stone. Stone men we were in terms of our utensils and weapons and what not. The building in stone was, as it was told to me, learned from the English, from the English settlers.

I am a registered Democrat who has never voted for a Republican and never plans to. I’m a Unitarian who listens to NPR and Stephen Colbert. But when I started publishing on the origins of New England’s stone heaps, the left ate its own. A NEARA official was “charitable” enough to call me intellectually dishonest rather than racist. I was accused of jingoism, of “spinning a myth”; journal editors were warned not to publish me. And my book was collateral damage during woke flaps at two publishing houses. Fortunately, New English Review Press dared to print it.

Ceremonial Stone Landscape activism generates political power by breathing new life into old racial anxieties. Its preservation campaigns are led by Native American identity bearers and demand compliance from whites. White supporters are morally redeemed allies of Native Americans, but skeptical whites are exposed as oppressors. CSL campaigns are about setting the political present straight, not getting the historical past right. And that perpetrates further racial injustice.

Many of New England’s stone walls were built by African slaves and Native Americans who had been indentured into white families or manipulated into a state of debt-bondage. In the nineteenth century, when the now-exhausted hill farms were abandoned, many farmers took their families and livestock westward to find fertile land, displacing indigenous populations on a massive scale. By denying these facts, CSL activists are erasing chapters of African American and Native American history.

Will this anti-historical movement lead to a deeper understanding of Native American people — or an even more romanticized image of them? Or will it collapse under rational inspection, and undermine genuine Native American place claims as it goes? After what they have suffered, the last thing Native Americans need is to be taken less seriously. They are being exploited by self-interested settler-colonists — yet again.

Timothy H. Ives is the author of Stones of Contention (New English Review, $20) and the principal archaeologist at the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission. This article does not represent the views of his office. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.