Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. President Biden may have promised that ‘America is back’, but the United States’ decades-long shadow war with Iran never left. Last month’s reciprocal strikes in Iraq and Syria, and a further 10 rockets launched at a US base in Anbar Province last week, were notable only for their normalcy. Far from being Biden’s ‘Hour One Crisis’, this kind of geopolitical hair-pulling via high explosives is all too normal in the post-Iraq War, post-Arab Spring hash of the Middle East.

Two American contractors and at least one Iraqi Shia militiaman are now dead. More casualties are likely to come in the weeks ahead. This first Biden counter-strike was no more than violent messaging, perhaps primarily to a domestic audience. That most hallowed of presidential qualities, ‘resolve’, was communicated — to the credulous anyway. For those who pay even intermittent attention to the Middle East, the kabuki theater of America’s armed engagement in the region is undeniable.

The US strike, conducted in the dead of night just across the Syrian border, was a seven-bomb pinprick. The Pentagon press secretary, former admiral John Kirby, stressed that the attack was ‘proportionate’ and ‘defensive’. The President apparently waved off on a second strike after a woman and children were spotted on the target. For that we should thank him. There have been enough kids killed in previous communications campaigns.

None of this, of course, is ‘restoring deterrence’, as the latest salvo by Iranian proxies proves. Absent a return to the nuclear deal and a concurrent cooling of tensions, or an inadvertent outright war that neither side wants, the region is probably in for more of this tit-for-tat.

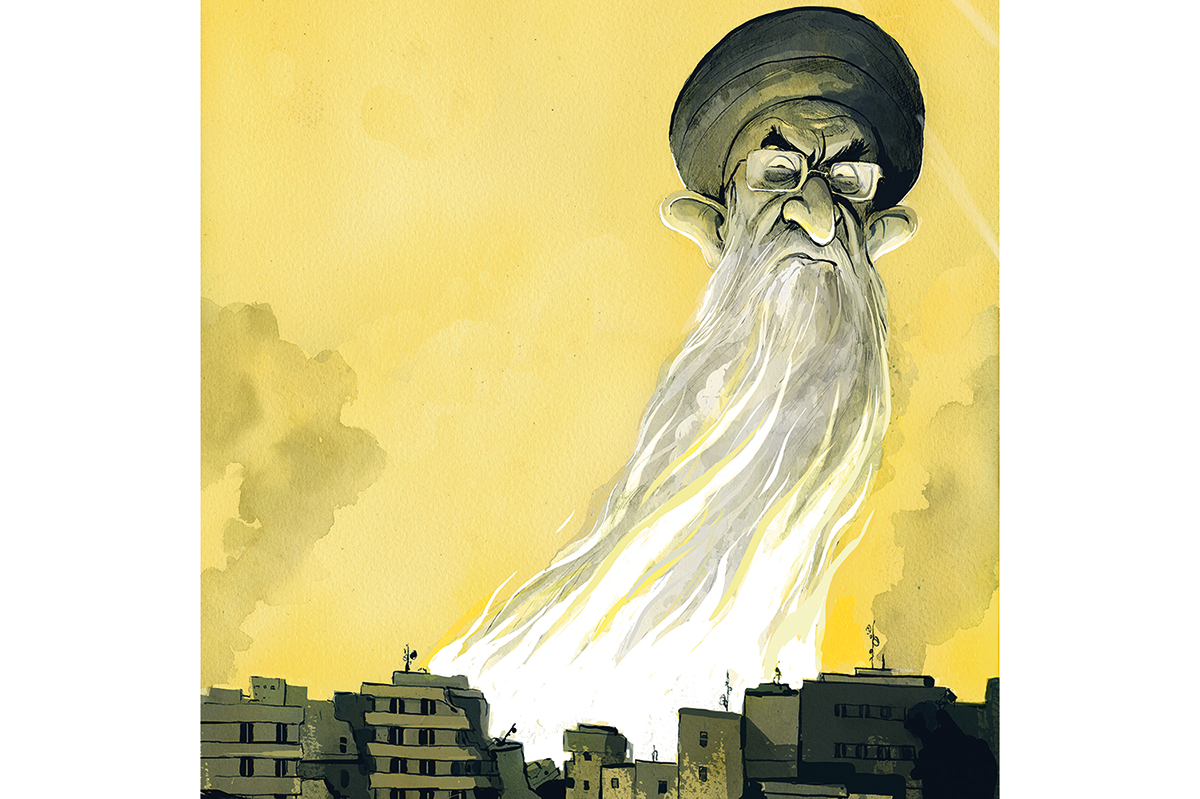

For all of Iran’s manifold and manifest weaknesses — a despised, brutal, sclerotic theocracy; an economy ravaged by sanctions, corruption, and mismanagement; epic failures of governance, from climate change to COVID — the Islamic Republic still holds a few useful cards.

The biggest of these are structural. A country of 80 million people, rich in human capital and inheritor to one of the oldest civilizations on earth, is unlikely to become irrelevant. When it is perched as both a gateway to Asia and a gatekeeper to some of the largest and lowest cost oil fields on Earth, it will command disproportionate attention.

If geography isn’t destiny, it is at least immutable. The enduring, limited American troop presence in Iraq and Syria, enough to get into trouble but not enough to solve problems, is a choice. Ostensibly there to harry the remnants of Isis in both countries, these advising and counter-terrorism teams cannot even secure themselves. They certainly can neither check Iranian influence in Iraq nor overthrow Bashar al-Assad in Syria, even as he rules over an abattoir. This continued deployment is quintessential American foreign policy: the triumph of hope over experience.

Alternate means of deterring Iranian harassment also come up short. A B-52 overflight last week was notable only for its Israeli, Saudi and Qatari wingmen. With US bombers able to strike the Maghreb from Missouri, Persian Gulf flyovers fall flat even as symbolism. Other methods are actively counter-productive. Double-pumping America’s most cherished white elephants, her nuclear supercarriers, to the Arabian Sea only drains the US Navy’s already exhausted crews. The Millennium Challenge debacle was almost two decades ago. Iran knows that the United States rightly fears for the survivability of its carriers against even a third-tier state threat.

There are also glaring asymmetries in attribution and casualty tolerance. Iran has acknowledged the loss of over 2,000 of its own men in the Syrian civil war, including more than one general. Losses among proxy fighters may be an order of magnitude higher. The killing of more of these militiamen will have no real impact. But the death of a single US serviceman could bring the United States and Iran back to the brink of war.

David Petraeus was far from a savior general but he did ask the most salient single question of the post-9/11 wars, a decade before he left the scene for the usual sinecures: ‘Tell me how this ends.’ We are only in the first inning of the Biden administration, but thus far the new team has yet to provide an answer.