I got my first Irish passport a few months ago. It felt like a vaguely transgressive gesture because my primary British identity was forged on the Northern Irish border where many Unionists like me paid for their UK citizenship in blood. In the event, if anything, I felt proud of the way this document allowed me to articulate a dormant part of my identity. Sinn Fein’s remorseless rise in this weekend’s Irish general election has strangled that hopeful feeling.

Sinn Fein have surged ahead to top the poll of first preference votes, smashing the Republic’s dominant two-party cartel that has ruled Ireland in coalition for a generation. The vote share of this insurgent movement has doubled since the last election to 24 percent, overtaking Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, neither of which have capitalised on a buoyant economy; and in Fine Gael’s case, in the shape of Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, a good war on Brexit.

Facts don’t care about my feelings. The nativist bigotry that characterizes Sinn Fein’s central philosophy. The gleeful baiting of nearly a million of their Unionist neighbors in the North. None of this cut any ice in the 26 counties.

Northern Ireland is a hermit kingdom with a mandatory coalition government only recently off its knees. It might as well be Mars for the huge number of the Republic’s voters, especially those under 24, who came out strongly for Sinn Fein. They want good affordable housing, decent infrastructure, an end to endemic rough sleeping and child poverty. And a healthcare system not disfigured by huge waiting lists. Older people baulk at pension reform which could see them working longer before retirement. Those in the middle want wages that keep pace with rampaging costs of living. There was plenty to aim at for the party of the ballot box and the Armalite.

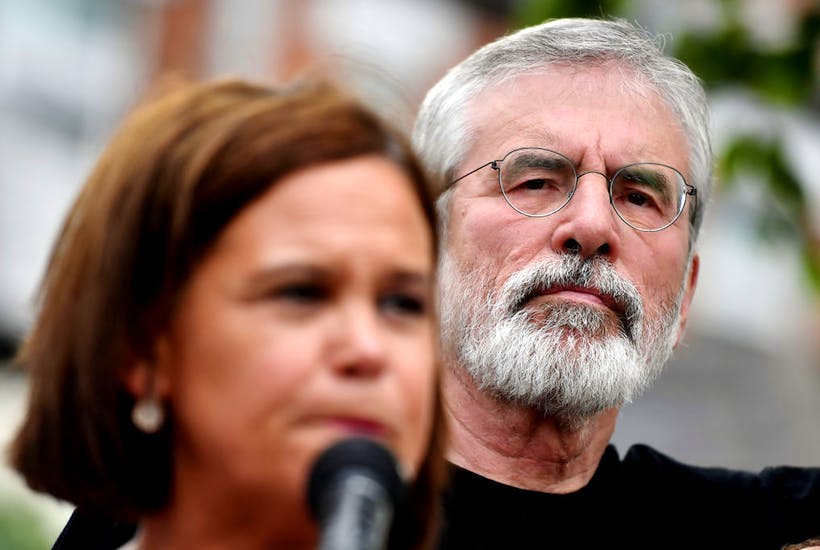

The Shinners are adept at producing Trojan horses. In more innocent times, their former leader Gerry Adams accidentally let slip that the way to break the ‘bastards’ in the North (the pro-British population) was to use ‘equality’ as the disguise for its virulently anti-Unionist agitprop.

Last weekend saw another triumph of packaging, as the primary objective of unification was concealed in the wrapping of uncosted, seductive and confounding promises. This spoke to an electorate born after the horror of the Troubles and seemingly oblivious to their bloody hands in it. It worked.

Sinn Fein, for now, are the third party of government, already installed in power north of the frontier. A party that still lionizes those in its former military wing, who carried out acts of unspeakable cruelty and sectarian spite just up the road, is in the running for the government of an EU state it has rejected since its formation. The evasion on moral accountability for IRA atrocities, the economic illiteracy, the boorish triumphalism and the cult-like attributes simply didn’t land a glove on people who have rejected a sclerotic polity in favor of change, any change, even with a whiff of cordite. For this, Varadkar, who only scraped into his own seat on the fifth count and his opposite number in Fianna Fail, Micheal Martin, have much to answer for.

Martin, who had previously said he would not be in any government with Sinn Fein, is now busily reversing out of that rhetorical cul-de-sac. The people have spoken and inconveniently flattened this low-risk moral high ground. This side of Sinn Fein’s spectacular gains, there now remains merely some ‘incompatibilities’. This sounds suspiciously like the first overtures to a Faustian pact, where constitutional government admits semi-housetrained democrats because that’s how power happens.

It’s still an unlikely prospect. The hatred and suspicion of the established political class for Sinn Fein might still outweigh Fianna Fail and Fine Gael’s ancient enmities. Many electoral permutations are still possible that could freeze Sinn Fein out of power. For now.

But we shouldn’t be too worried about Shinners with their boots underneath the Irish cabinet table. Unlike in the North, where rendering that part of the UK ungovernable, while, er, still being in government, had some twisted strategic logic to it, there’s nowhere to hide for a populist hard-left party charged with making difficult decisions as opposed to protesting them.

They are unlikely to make the transition well as in the case of so many recent populist movements across Europe, who seize power promising the earth but are ultimately vanquished by hubris and incompetence.

Sinn Fein’s obsessive demands for a unification poll have received a quantum boost in this election from people whose visual conception of Northern Ireland is largely a blank space with the legend ‘here be dragons.’ It’s an unwelcome paradox, as is the possibility of the very people who stand in the way of even a discussion with Unionists about a different Ireland being given such a huge mandate to agitate for one. For those of us who were just becoming reconciled to this vital part of our identity, this is a blow but not a mortal one. To paraphrase Heaney, be advised, neither of my passports are green.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.