Is COVID accelerating the eclipse of France and the UK as ‘great powers’? For over two centuries Paris and London have been seated at the top table in world affairs. The essential element of their power has been economic, allowing both states to maintain powerful defense budgets, pursue active foreign policies and in the last resort, to wage war.

Since 1945, although their power has in relative terms continued to decline, they have remained great power players as two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, and as two of the five official nuclear powers able to project force to all regions of the globe by dint of nuclear armed navies, notably submarines. This continues to be possible as long as they remain the fifth and sixth largest world economies. But this weekend French official GDP figures showed a shocking 13.8 percent contraction of the French economy in the second quarter of 2020 (Eurozone 12.1 percent), the worst since 1944. Even allowing for an unlikely V-shape recovery, France will not return to 2019 levels until 2022. Britain’s economy will fare little better.

Projections by the World Bank and IMF, that do not fully take into account COVID’s impact, project that by 2024 the UK and France’s GDP (in PPP) will have slipped to ninth and 10th positions, respectively, in world rankings. This unprecedented decline would put India, Indonesia, and Brazil ahead and Germany in seventh position behind Russia. Even allowing for the World Bank and IMF’s habitual economic pessimism when it comes to predictions about western economies — see Brexit — the trend is not fanciful.

This is a serious situation for two reasons. First, Britain and France will no longer possess the economic clout to sustain their continuing world roles. Second, it confirms a longer-term trend of the eclipsing of Europe as the geopolitical heartland of world affairs with concomitant impact on Paris and London as centers of power. Given COVID’s impact in Europe, the lackluster response of most European governments and their underperforming health systems, the region’s ‘soft-power’ loss will also further impact Britain and France, as I wrote in The Spectator here.

The power of the British and French economies has also compensated for their demographic deficiencies since World War Two. But forward projections show an acceleration in their relative economic and demographic decline. Of those economies predicted to be the largest in the world in 2024, Britain and France have by far the tiniest present-day population.

[special_offer]

So what can be done in London and Paris to forestall this outcome? The answer requires something the length of a white paper. But what must be avoided is that these predictions become the basis for a renewed culture of ‘declinism’ in either state. Declinism is what gripped Britain in the 1960s, encouraging its elites, notably political and administrative, to think of the European community as the lifeboat for Britain’s Titanic. Or, in the words of Sir Con O’Neill, Britain’s principal negotiator to the European Commission from 1970-72, to avoid Britain declining to ‘a greater Sweden’. The panic came about, as Robert Tombs convincingly shows in his forthcoming history of Brexit, because of elite anxiety about ‘losing an empire and not finding a role’, according to Dean Acheson’s famous quip. It also resulted from economic illiteracy and envy; seeing higher growth rates in the Common Market and not understanding their transitory status, while Britain continued its more modest but longer-term growth. It seems many Remainers would still be prepared to repeat this mistake.

As for France, it too became gripped much later by a culture of ‘declinism’ from the late 1990s to the present. In 2013 73 percent of the French believed their country was in decline. Anxiety about France’s relative decline — notably in relation to its old bellwether Germany — has led her elites to clutch at more European integration as a means of slowing German ascension and in the hope of boosting her own. That has not paid off either. The latest version is the leap in the dark of European debt mutualization that will see France and her economy further deprived of autonomy, more dependent on Germany, and the French people further frustrated by their country’s strait-jacket.

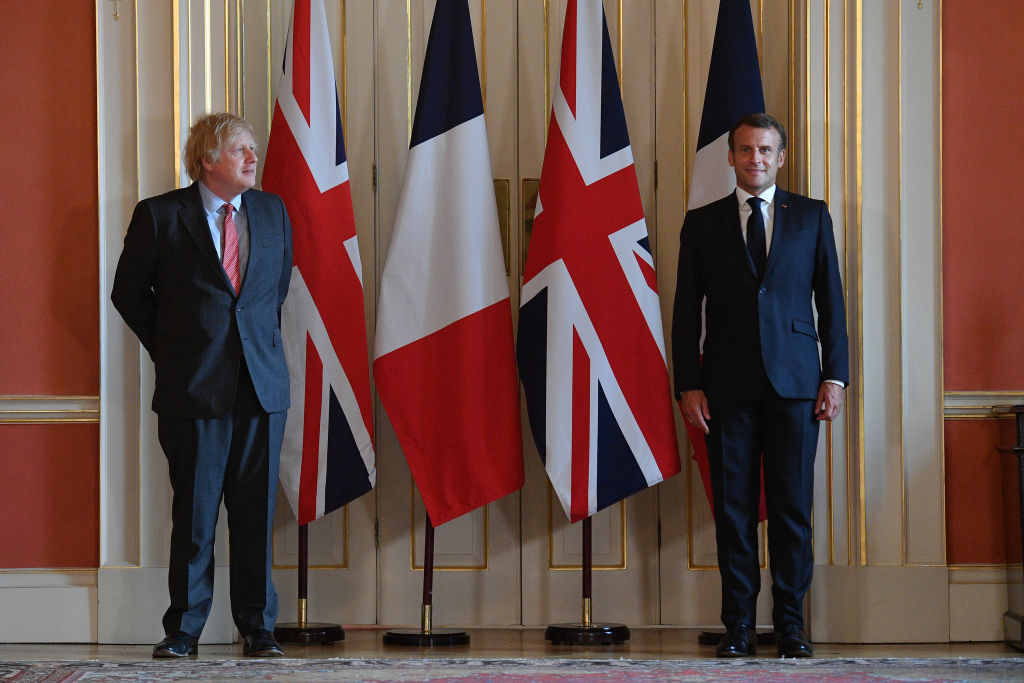

Whilst France and Britain’s economies may evolve in different ways post-Brexit, there is one area in which closer cooperation can be beneficial to both: foreign and defense policy. Given the inflexibility of the EU in the Brexit negotiations there is little interest in Britain signing up to closer EU defense and foreign policy, which lacks teeth anyway. But it is worth doing so with France with whom structures already exist in the form of the bilateral foreign and security treaties of Saint Malo (1998) and Lancaster House, whose 10th anniversary will be celebrated this November. Given President Macron’s declaration in August 2019 to France’s ambassadors that whatever the outcome of Brexit, London and Paris will cooperate intimately on the world stage, expect the two countries to make a big deal of the November celebrations. Both Macron and Boris believe that Britain and France together can manage their world roles to far greater effect than singly or with the EU in its present form.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.