The British High Court has allowed Julian Assange to appeal once more against extradition to the United States on the basis that no sufficient assurances have been received over his ability to rely on the First Amendment if tried there.

We don’t know what the result will be (Monday’s hearing merely gave permission to appeal, with no guarantee as to its outcome). Nevertheless, we should still think twice before we hope that the appeal will ultimately be dismissed, thus allowing the final removal of someone who has been a thorn in the UK authorities’ side for nearly fifteen years.

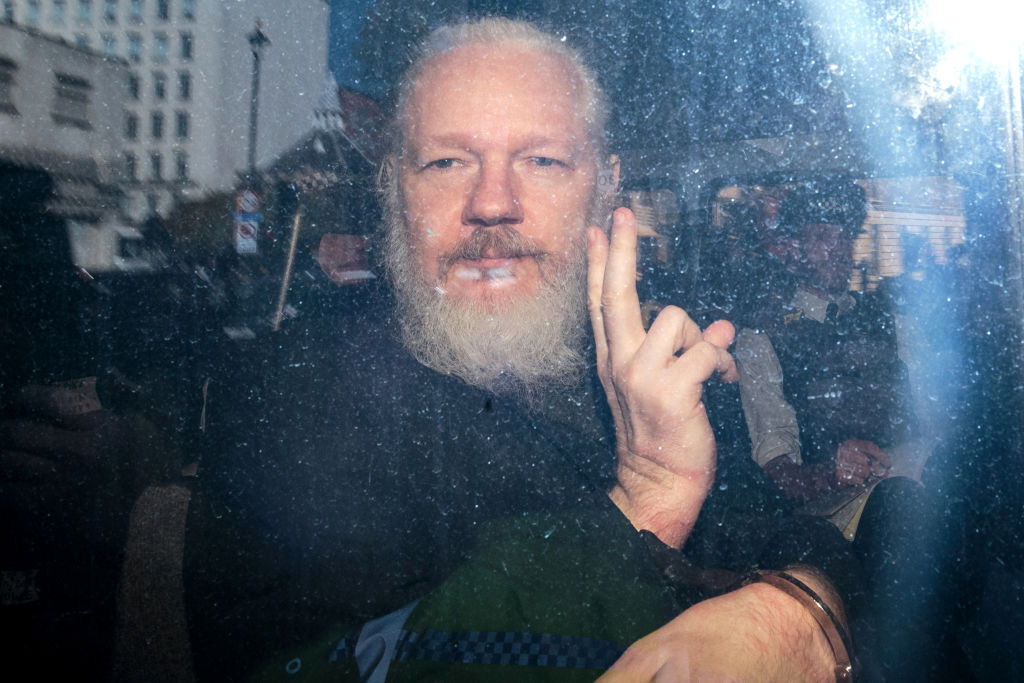

This is Assange’s second brush with extradition law. In 2012, he stymied a largely ordinary rendition to Sweden on charges of sexual assault and rape (which he denies) by remaining holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London for seven years, until the Swedish government lost interest. The present request by the US, the subject of Monday’s hearing, was on entirely different charges, namely conspiracy to obtain and disclose US defense information contrary to the Espionage Act, arising out of the Chelsea Manning leaks which he collaborated with the Guardian in publicizing, and also in large measure revealed in Wikileaks, in 2010. Assange denies any wrongdoing.

In law there is no doubt that, subject to any quibbles over assurances from Washington, this is an entirely regular request from the State Department. There are nevertheless several reasons that should give us pause about allowing extradition for state crimes of this kind.

One is the effect on press freedom. True, technically Assange is alleged to have committed an offence in the US by suborning people there to provide him with secret information. But the essence of Washington’s complaint is that Assange, a journalist in England with no connection with the US, has published, in England, material classified in the US that is contrary to US espionage law. Admittedly in this case the leaks could hurt Britain too, since we make much common cause in defense with the US. But this will not always be so. Imagine a request from, say, South Africa, India or Brazil, alleging abstraction of classified information there on the orders of a UK columnist and its publication there. The same would apply. Unless the journalist can show a likelihood of prejudice or oppression if sent for trial, extradited he must be. In short, the vital ability of the press in Britain to publish what it likes about foreign regimes provided it obeys our law, whatever their own law may say, is now seriously in doubt.

The second reason is more general. Fifty years ago, UK law did not only bar extradition of those likely to face persecution. It also, broadly, prevented extradition for any non-terrorist offense of a “political character,” something that automatically excluded matters such as espionage and other anti-state offenses. Unfortunately, this principle was abandoned as regards European states with the adoption of the European Arrest Warrant (something which, three years ago, nearly led to Clara Ponsati, a vocal Catalonian separatist who later took up a teaching job in Scotland, being forcibly bundled onto a plane to Madrid to face criminal charges of subversion before a Spanish court). Later in 2003 the Labour government suppressed the principle altogether in a new Extradition Act.

This is unfortunate. An attractive feature of Britain was once a libertarian insistence that, however friendly its relations with another state, friendship did not extend to helping that state with its dirty work in rounding up subversives. But today libertarianism of that kind is unfashionable. Even if you have fallen foul of your government, you are in the UK’s eyes just like any other criminal: if your government makes a request, even for a state offense, the UK will happily hand you over unless you can show that you are likely somehow to receive unfair treatment when sent back to face it: something that can be easier said than done.

And this raises a third point. Whatever you may think of asylum claims in general, the extradition rules that the courts now have to apply subvert what was once a proud British tradition. In the nineteenth century, UK political life was much enriched by the fact that critics of foreign governments were allowed, assuming they were reasonably well-behaved, to carry on their campaigns here. Not only did the law protect them from rendition for offenses like sedition; in addition, all extradition requests had to be approved by the home secretary, who if he felt that the foreign government was overstepping the mark, could simply refuse to give effect to them. This too has unfortunately gone. The entire process is now legalistic: if the legal requirements for extradition are satisfied, then whatever the home secretary’s view, he is bound by law to go ahead with the extradition.

In short, Britain has now apparently bound itself in a tangled web of law to abandon its tradition of harboring dissidents, and has to hand over someone in Julian Assange’s position, whatever electors and their representatives think of the case and whatever the knock-on effects on the freedom of the press. The UK now needs a movement to draw attention to this. There is much to be said for Rishi Sunak setting up a body to revisit UK extradition law to make sure this kind of thing does not happen in future.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply