It is not often that an American politician publishes a book of genuine interest. It is even less often, breaking through the veil of ghostwriters and marketers and political risk consultants, that such a book provides real insight into its author.

Hillbilly Elegy is an obvious example: an unusually vulnerable self-portrait whose sales shot through the roof after J.D. Vance was tapped to be Donald Trump’s running mate this summer. Josh Hawley may never be vice president, but his ambitions and his politics are already apparent in the biography of Teddy Roosevelt he published a full sixteen years ago. Richard Nixon’s Six Crises was intentionally prophetic as the man and the nation neared a fork in the road, and Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia foretold troubles far worse than Watergate (even if it didn’t mean to). The Art of the Deal, as an extraordinary case, can be read retroactively into the tradition.

And then there’s Sheldon Whitehouse, backbench Democrat of Rhode Island and author of The Scheme: How the Right Wing Used Dark Money to Capture the Supreme Court. The Scheme may not be of much interest, but it certainly tells its reader something about the man whose name is on the cover.

Whitehouse is a lawyer (Yale ’78, UVA Law ’82), as is his “co-author” (read: author; Harvard Law School, Class of 2000). So there are semi-substantive points scattered throughout the book, such as his procedural objection to appellate court fact-finding. On balance, though, it’s all there in the title: the book argues that the existence of a single conservative legal interest group (the Federalist Society, dwarfed in size and scope by the ACLU and a dozen other left-wing juggernauts) has shaped national discourse on jurisprudence to a degree amounting to the capture of the levers of American government by a “dark money” cabal — that is, corporate giants hidden behind layers of NGO obscurity.

Whitehouse himself prefers his money light — very light. Among the minor scandals that have plagued the senator’s fairly inconspicuous career is his family’s membership at the exclusive Bailey’s Beach in Newport, his hometown and the traditional summer retreat of the Yankee aristocracy. The elite establishment’s reputed all-white membership drew liberal scrutiny to Whitehouse’s summertime habits in the latest racial reckoning. (Not enough scrutiny, however, for the Whitehouses to withdraw.)

Whitehouse’s place among the Newport elite is the key to understanding his politics — including his current feud with the Supreme Court. These days, it is common for members of Congress to make their millions by preternatural prowess in the stock market. And the junior senator from Rhode Island is no stranger to the Hill’s extremely “lucky” trading habits, having dumped his hefty stock portfolio the moment he learned from Ben Bernanke of an impending crisis in September 2008. Nor did Whitehouse learn his lesson about appearances after that fact became public; in 2022, he failed to disclose purchases of Target and Tesla stock as required by law for all members of Congress, and a New York Times investigation that year placed him among the ninety-seven lawmakers who had benefited from personal stock trades connected to their work (and access) on the Hill.

But unlike others who have taken election to the legislature as a ticket to the upper class, Whitehouse’s shrewd trades (in which he denies any impropriety) merely serve to preserve a fortune established long ago. In the age of Kamala Harris’s prosecutor-cum-wine-mom mash-up, of Tim Walz’s phony heartland populism, of Nancy Pelosi’s pantsuit managerialism, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse — whose very name is an almost-too-canny callback to a bygone era — is a relic: the last patrician liberal. (Other uber-wealthy Democrats like J.B. Pritzker do not quite match the form.) Whitehouse is a man not just of means but of breeding; that used to mean something in a Washington where the Kennedys were regarded as a déclassé intrusion.

Not long ago, men like Sheldon Whitehouse were firmly entrenched as the ruling power in our nation’s capital. By the end of the nineteenth century, the subjugation of the Southern aristocracy, the advent and expansion of the federal bureaucracy, and the reform of the North’s best universities on a European model converged with broader economic trends to birth America’s first managerial elite, manned by the second and third sons of respectable WASP families.

For generations, these WASP lords of the swamp ruled nearly every corner of the federal government. From the wreckage of World War Two, as America entered the role of a global superpower, they formed an imperial service not unlike the one their British cousins once had occupied, revolving around the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency and the newly gargantuan State Department. Their exodus from the halls of power began with the fall of Alger Hiss and was declared complete prematurely at the death of George H.W. Bush, yet the WASP ascendancy echoes even to today.

Charles Sheldon Whitehouse, the senator’s late father, served this power structure faithfully at its peak. Reared as an elite with a real sense of noblesse oblige, Charles — much like his contemporary, Bush — interrupted his studies at Yale to serve as a Marine Corps pilot in the Pacific Theater, where he was decorated highly; his younger brother, George Bruen Whitehouse, did not return. After war’s end, with diploma in hand, this dutiful WASP spent nine years at the infant CIA and twenty-two at State. The elder Whitehouse was the number two US diplomat in Vietnam during some of that war’s most difficult days — that is, during the great boondoggle that epitomized the hubris and foreshadowed the downfall of the WASP establishment.

Charles’s own father, Edwin Sheldon Whitehouse, was a diplomat as well. The son of a fantastically wealthy New York lawyer, Edwin was shipped off to Eton for his schooling before returning (as is proper) to matriculate at Yale. (The senator’s diploma from St. Paul’s, a favorite prep school of Yankeedom’s upper crust, is unimpressive by comparison, and while he managed to continue the family tradition at New Haven, he did not follow his father and grandfather into Skull & Bones.) As an embassy staffer in Paris, Edwin Sheldon Whitehouse provided the car used to smuggle Alexander Kerensky out of Russia during the October Revolution.

The illustrious branches of the Whitehouse family tree are almost too many to number. Two of Sheldon’s great-aunts married into nobility — one English, one Russian. The twelfth Earl of Coventry, the senator’s first cousin once removed, died without a male heir in 2004. The Russian branch seems to have survived the revolutions at least as well as Kerensky, though it dwindles out into obscurity somewhere around Sweden.

A great-grandfather, Henry John Whitehouse, was for the decades surrounding the Civil War the Episcopal bishop of Illinois. (The Episcopal bishopric breeds a certain type: Dean Acheson’s father was the bishop of Connecticut.) This Whitehouse too was a controversial figure, as much for his belief in the real presence as for his Confederate sympathies. One contemporary described Bishop Whitehouse as “a thorough aristocrat by birth and training and accustomed to every luxury” — and so it took nine years for the diocese to meet his exigent salary demands (during which time the bishop declined to take office). The same colleague worried that Bishop Whitehouse “lack[ed] completely the power of seeing the effect certain positions taken would have on the public, how men would estimate them, what would be the public judgment of them, whether a wise and eminently proper expediency did not counsel another course.”

Perhaps the senator’s most colorful ancestor, though, is Charles Crocker, a founder of the Central Pacific Railroad and onetime majority shareholder of Wells Fargo. Crocker was a self-made man, who began his career as a teenage laborer in frontier Indiana. Half a century later, he was the proud lord of one of San Francisco’s most impressive Second Empire manors. When the owner of an adjacent property refused to sell to Crocker, the railroad baron built a forty-foot-tall fence around three sides of his neighbor’s lot. Crocker got his hands on the property only when the neighbor and his wife both died, after more than twenty years; it was only two more before the mansion was destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. (Faithful WASPs to the bitter end, Crocker’s heirs donated the devastated lot to the Episcopal Church; Grace Cathedral stands there to this day.)

That need to feud runs in the blood, but the age of forty-foot fences is long past. Crocker’s great-great-grandson must content himself with sparring with the Republican majority of the Supreme Court, the one seat of power in America not occupied today by the melting-pot successors of the old patrician liberals.

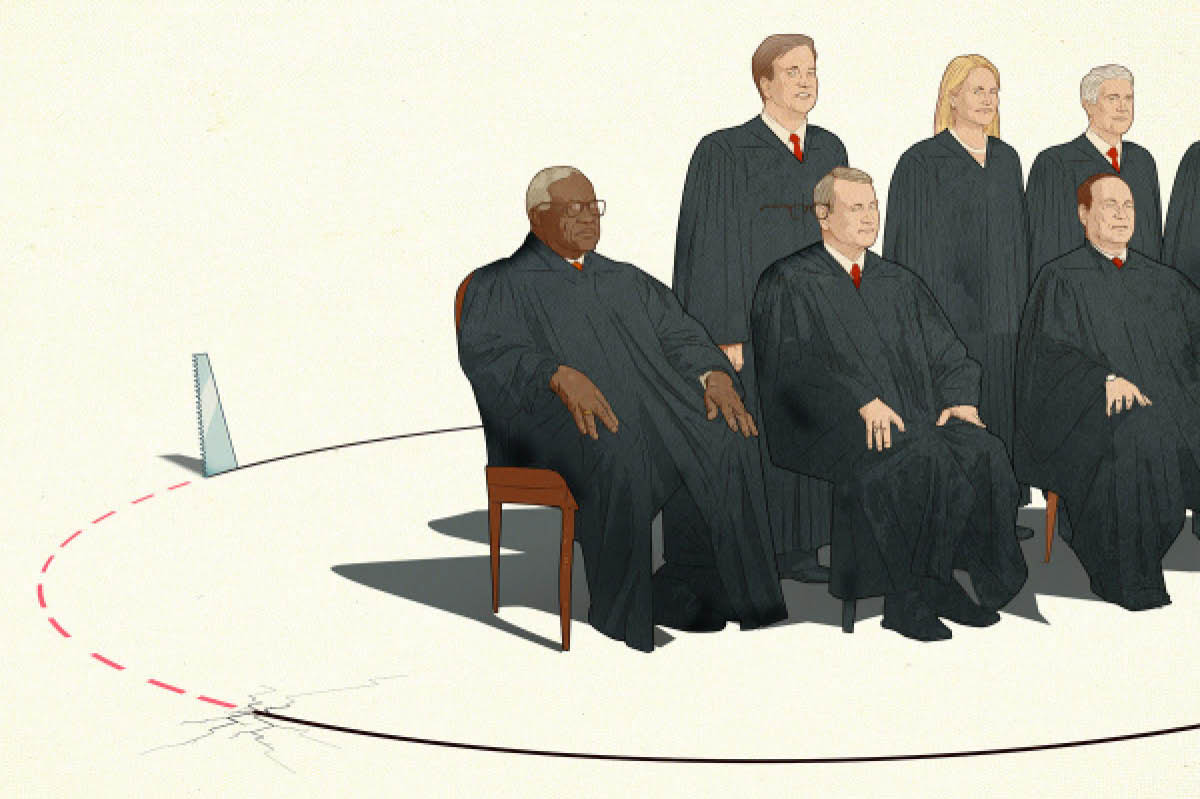

Clarence Thomas has come in for the harshest treatment lately, ostensibly due to the fact that he has a friend who happened to be very wealthy, and that the two men occasionally spent time together. (The membership roll at Bailey’s Beach is famously non-public; surely Senator Whitehouse prefers it remain that way.) From his perch as chairman of the Courts Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Whitehouse has pushed rules changes that would prevent justices from accepting hospitality and called for a special counsel investigation into Justice Thomas’s alleged misdeeds.

When then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett appeared before the Judiciary Committee as President Trump’s pick for the highest court, Senator Whitehouse spent just shy of twenty-nine minutes conspiracizing about her supposed place in the “dark money” scheme to make the court less liberal — all without posing a single question to the nominee. And Whitehouse — perhaps banking on the WASP camaraderie of his father’s era — even tried to sic the FBI on Justice Brett Kavanaugh by publicly, repeatedly scolding Director Christopher Wray for failing to hamstring Kavanaugh’s nomination. The pattern here — like the divide between Thomas, Barrett and Kavanaugh and the patrician insider Whitehouse — could hardly be more clear.

That the waspish Sheldon Whitehouse would war with ethnic-Catholic institutions of civil society was established early on: among his first career victories as a US attorney in Providence (long before the Whitehouse wrath landed on the late Justice Scalia) was the first-of-its-kind conviction of mobster Gerard Ouimette under the three strikes provision of the Biden-Clinton 1994 crime bill. And that SCOTUS would find itself in the WASP liberal’s crosshairs is hardly a surprise. A court is, by its nature, a conservative institution. And by its composition it resists (at least to a degree) both the submission to personality and politics inherent in the elected branches and the risk of cultural capture to which a large-scale bureaucracy is prone. Just as the presidency was once the viable rival power to the WASP deep state — landing Kennedy and Nixon both on the chopping block — the Court is now the likely rival to its successor regime.

Certainly Sheldon Whitehouse is convinced of that fact. Fighting off a primary challenge in September, he told a local news outlet that Rhode Islanders ought to send him back to Washington because he is “leading the fight to clean up the mess at the Supreme Court, which is delivering for the billionaires who paid to capture it while taking away the freedom of women to make their own life decisions and the freedom of kids to be safe in their own schools.”

Whitehouse is banking on the fact that his crusade against the Court can win elections. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris must have made similar calculations, given their late-in-the-cycle drive on judicial issues. But what exactly does “leading the fight” look like here? Besides supposed ethics reforms and the pie-in-the-sky dream of relitigating Roe, it could mean term limits for the only officials to whom the Constitution provides lifetime appointments — a cruel irony inflicted by a senile man (or whichever faceless handler is running the government these days).

Whitehouse’s particular proposal to this end would see one new justice begin an eighteen-year term every other year. The prevailing sentiment on the Hill is that a Democratic majority next session would be virtually guaranteed to pass this and any other reforms the Whitehouse contingent puts forward.

The last politician to seriously attempt such a radical transformation of the Court was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who (Dutch last name notwithstanding) was an exemplar of the WASP nobility, in all its paternalistic splendor and confidence. Roosevelt’s most ambitious plans for the Court were his most public failure, but he mounted revolutions elsewhere, and he left behind both a liberal majority in SCOTUS and a leviathan government dominated by liberal Yankees very much like himself.

The Court outlived that regime, and it survived through generations of lunatic justices to be restored to order by the careful appointments of four Republican presidents. This is the one great failure of the liberal WASPs in whose footsteps Sheldon Whitehouse travels — a failure whose sting endures through generations. Sheldon Whitehouse is not a man disposed to forget the past.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply