Northwest Syria is one of the most wretched places on earth. The Syrian province of Idlib, straddling the border with Turkey, is a haven for the internally displaced and is in all practicality a state within a state.

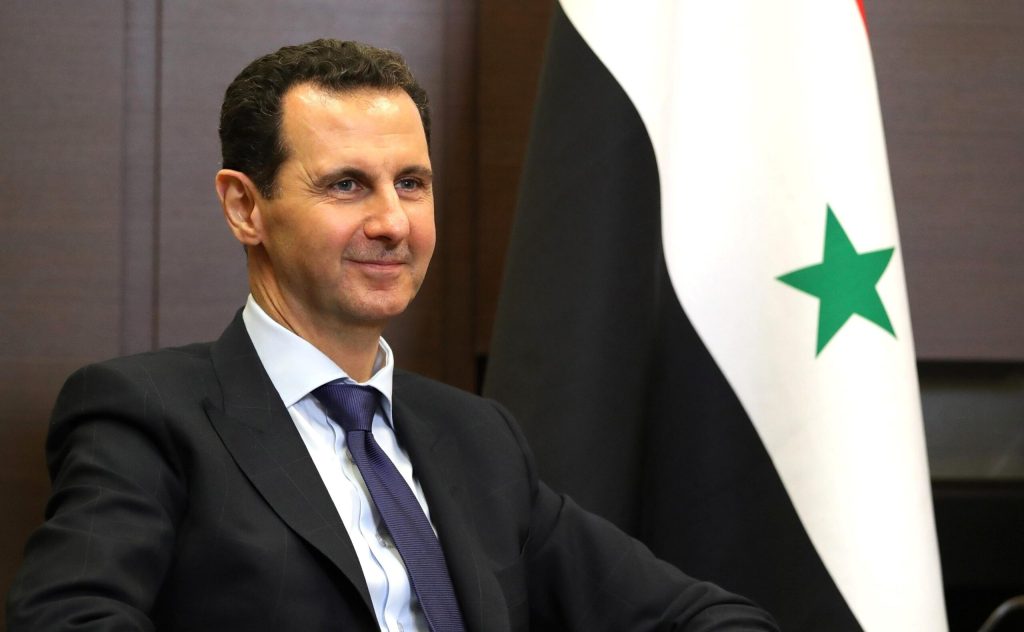

Throughout Syria’s twelve-year-long civil (and proxy) war, Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad has treated the area as a dumping ground for fighters who refuse to lay down their arms and civilians who want nothing to do with Assad family control. Idlib, representing 4 percent of Syria’s total land, is now host to 25 percent of its entire population.

And that was before the earthquake hit. If Syria’s northwest was a gateway to misery before the tremors, it’s now a hellscape. Entire families have been wiped out. Buildings have been reduced to rubble. Rescue workers, without adequate supplies or funding, have been forced to dig for survivors with their bare hands. Thousands have been killed, and hospitals that were already dilapidated, under-equipped and short-staffed are now working at full capacity.

Assad, once the world’s most hated man, has sensed an opportunity. He’s been projecting himself as a responsible, empathetic leader who cares about the same people he once bombarded with barrel bombs and chemical weapons. This week, the Syrian government approved the opening of two additional humanitarian aid routes from the Turkish border into Idlib. Immediately thereafter, UN-organized aid trucks began transporting supplies into the area. Assad is playing the part of a benevolent dictator, traveling alongside his wife, Asma, to neighborhoods in the north severely affected by the earthquake and visiting the injured.

For Syrian activists still working to depose the strongman, the earthquake is a curse. Assad, who burned Syria to the ground in order to maintain his family dynasty, is exploiting a natural disaster for his own benefit. “The earthquake gave the regime an advantage to survive politically,” Omar Alshogre, a Washington, DC-based member of the opposition, told CNN. In a commentary for the Financial Times, Kim Ghattas advised American and European officials not to fall for the ruse: “Syrians should neither be forgotten nor offered as a sacrifice in hasty compromises because the region and the west have been worn out by [Assad’s] intransigence.”

The United States is not looking to normalize Assad anytime soon. It’s difficult to see Joe Biden or any president reconciling with Syria as long as Assad is sitting in the presidential palace (and at fifty-seven years old, he could rule Syria for another two or three decades). Europe as a whole, which prides itself on being a symbol of liberty and a defender of universal human rights, is unlikely to confer normalization upon the Syrian dictator either.

Assad, however, doesn’t need to be embraced by the West in order to preserve his power. While it’s true he would like US and European sanctions lifted, Assad’s continued rule over a shattered Syria doesn’t depend on it. The bigger priority at the moment is reconciling with his Arab neighbors, like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which once financed the insurgency against him.

He is well on his way. The popular description of Syria as the black sheep of the Arab world has long been overtaken by events. The UAE resumed diplomatic relations with Assad’s government in 2018, as did Bahrain. Jordan’s King Abdullah II, who previously hosted a CIA program to organize anti-Assad rebels into a cohesive fighting force (which turned out to be a disaster), is no longer shunning the Syrian dictator; Jordanian foreign minister Ayman Safadi arrived in Damascus today. Two days earlier, UAE foreign minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed did the exact same thing, a visit that came less than a year after Assad traveled to the UAE to meet Crown Prince (now King) Mohamed bin Zayed.

The Saudis are doing their own outreach, albeit in more discreet ways. Saudi planes are delivering loads of aid through Assad-controlled territory. Even Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who labeled Assad a butcher and was one of the first to call for no-fly zones inside Syria, isn’t ruling out a formal sit-down with him.

US officials back in Washington look at all this and feel shivers in their spines. Sending humanitarian aid is one thing, particularly during a tragedy beyond anybody’s control. The provision of aid shouldn’t be politicized, period. To the Biden administration’s credit, the Treasury Department has temporarily suspended its sanctions regime against the Syrian government to ensure humanitarian organizations are able to finance and deliver assistance.

Yet Washington would rather its partners in the Middle East refrain from establishing deeper economic and diplomatic ties with Syria. The Biden administration has made this point again and again, even scolding countries in the region for the slightest move away from that position. When the UAE granted Assad a visit last year, the State Department said the US was “profoundly disappointed and troubled” by it. Turkey received the same treatment when Erdogan broached the subject of a hypothetical meeting: “We do not support countries upgrading their relations or expressing support to rehabilitate the brutal dictator Bashar al-Assad,” State Department spokesman Ned Price said.

Yet as the White House is learning, different states have different interests as well as a sovereign right to make their own foreign policy decisions. The West may not like it, but the Middle East is moving on. And the region’s governments have long since concluded that the wily tyrant in Damascus is here to stay.