No one likes to waste a good crisis, and the digital-payments industry is certainly trying its hardest to spin the narrative that COVID-19 is about to deliver the coup de grâce to cash.

Various lobbying efforts culminated in a recent CNBC report claiming we have all switched to payment apps to avoid catching the disease from dollar bills. A ‘cashless customer’, Heima Sritharan, supposedly speaks for the entire millennial generation: ‘Not that I was using cash that much before, but I find that during Covid especially, I just don’t want to use cash as much because of the germs aspect.’ The report quotes a figure from the Pew Research Center suggesting that 34 percent of consumers under the age of 50 went the previous week without making a single purchase with cash.

Yet there is a very large, inconvenient fact standing in the way of the claim that the US is about to become a cashless society where everyone happily goes about happily paying for everything by card or phone and never deigns to touch paper money or coins ever again: the quantity of cash in circulation keeps going up and up.

On December 31, 2019, just before the pandemic, the Federal Reserve put the value of physical currency in circulation at $1.76 trillion. That itself had doubled in a decade, in spite of Apple Pay, Google Wallet and all the other digital payment apps, but since Covid the growth of cash in circulation has accelerated. In January 2021 it hit $2.1 trillion: a 20 percent increase in just 12 months. If we are frightened of catching the virus from our dollar bills, we have a funny way of showing it.

There was a similar, if less pronounced, acceleration in cash in circulation during the 2008-09 financial crisis, and little wonder. With banks threatening to go bust, taking down their depositors’ funds with them, cash was a relatively safe place to be. True, there is a danger of an intruder turning over your house, finding your hidey-hole and running off with your savings. But when you have just watched Lehman Brothers collapse on the TV news, that perhaps seems the lesser danger.

We haven’t, so far, seen bank collapses during this crisis, but the same principle applies. When the world is in economic crisis, people run towards cash as a safe haven. Or at least they do during an era of low inflation. It would have been a different matter in the 1970s, when the value of physical currency was eroding quickly. But what is there to lose when you are earning zero interest?

In the near future, a zero-interest bank account might seem a good deal. What we have seen so far in terms of the growth of dollar bills in circulation is nothing compared to what we would see if banks started trying to impose negative interest rates on retail depositors — where we would have to pay for the privilege of lending our money to a bank. That, indeed, is one of the reasons why we should beware a cashless society, and why many figures in government and central banks would love to impose one. In 2009 they tried to stimulate the economy through ultra-low interest rates. But they used up all their ammunition. They know they can’t reduce interest rates any lower — i.e., turn them negative — without generating a run on the banks as people object to being charged on their savings. The only way they could get away with negative interest rates is if they abolished cash first.

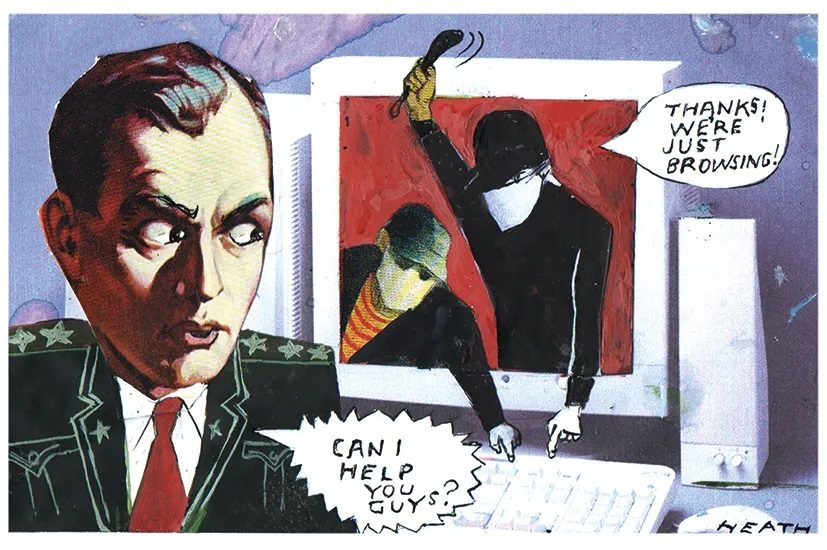

The case for saving cash is much more than the dry subject it might at first appear to be. It is a moral and spiritual battle between the people on the one hand and government and corporate power on the other. It is easy to see the profit for companies which produce payment apps: the chance to earn swipe fees and, no less, the opportunity to capture large quantities of valuable data on our spending habits. For governments there is the prospect of imposing negative interest and — they hope — increasing the collection of tax revenues. Moving all transactions to electronic form might indeed squeeze a bit more tax out of the little guy, but is that really where most tax revenue is lost? Criminals and tax-evaders alike have long since mastered the internet, the dark web, crypto currencies and the like. What is in a cashless society for the rest of us? True, it is often more convenient to use digital forms of payment. But we don’t need a cashless economy to do that: we only need the choice. All that would be achieved by banning the use of cash is to take away that choice and disenfranchise the poor and unbanked. That is why New York, Philadelphia and San Francisco, among other cities, have banned cashless stores.

Even the claim that physical cash presents an infection risk has been debunked in recent months. At the beginning of the crisis, experiments showed how the live virus could linger on surfaces for several hours. Yet as time has gone on, the evidence for transmission via physical contact with surfaces has grown weaker, and the evidence for transfer via airborne droplets is now stronger. Microbiologist Emanuel Goldman of Rutgers University has pointed out that laboratory tests have used quantities of virus far larger than those which would be encountered in real life. To catch COVID from a dollar bill someone would deliberately have to sneeze on it, and even then you would have handle the bill within an hour or two to be in any danger. In other words, if you are a millennial worried about catching COVID, it’s going to parties and crowded bars, traveling and meeting friends you need to stop doing, not buying stuff with dollar bills.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.