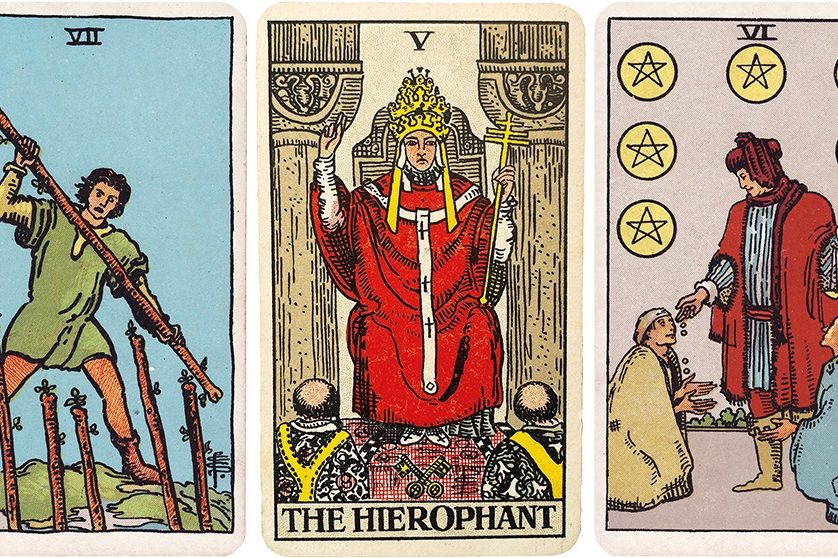

Among my many fake and useless skills, I’m a reasonably decent tarot reader. I can do one for you now if you like. A very simple three-card spread: your cards are the Seven of Wands, the Hierophant and the Six of Pentacles. There are lots of vaguely drippy ways of interpreting a three-card spread: past-present-future, or mind-body-spirit; I usually prefer to think of the cards as representing first, the mess you’re in; second, how you got there; and third, how you might plausibly manage to get your way out. And you, reader, are in a bit of a mess.

If you look up the Seven of Wands online or in a book, you’ll discover that it’s about struggle and difficulty; it means you’re constantly defending yourself from various envious rivals, all trying to tear down whatever it is you’ve achieved. The image shows a man on a hill, fighting off a thicket of jabbing sticks that seem to emerge from underground. The Hierophant depicts a figure in Papal regalia, seated on a throne; it stands for order, orthodoxy, conformism and tradition. In the Six of Pentacles, there’s a rich merchant dropping coins over the beggars that kneel at his feet. It stands — no surprises here — for generosity. The meaning seems obvious. You’ve found yourself constantly under attack; this is because you’re too hidebound and conservative; maybe they’ll lay off you if you start giving some of your money away. You’re a Spectator reader. It all makes sense.

But what I really like about tarot are the meanings you can’t look up online or in a book. In an actual reading, your first task is always to study the cards, really look at the pictures and think about what they might mean. The deck I used for your reading is the Rider-Waite, which has been the world’s bestselling tarot ever since it was first published in 1909. The Rider-Waite cards are full of fun little details. In the Seven of Wands, for instance, the man on the hill is wearing two different shoes: he’s so surprised by all these poles suddenly being shoved in his face that he hasn’t had time to dress properly. But some of these details can complicate any too obvious reading.

According to all the guides, the merchant in the Six of Pentacles is doling out charity to two beggars. But he’s not; what we actually see is him giving coins to one beggar, and not even looking at the other. Maybe the solution to your problems isn’t as clear-cut as it seemed, but then your problems might not be either. Look again at the Seven of Wands. Six of the wands are the ones being hefted by some unknown enemy at your feet. But one of them is the one in your hands, which you’re using to fend them off. Is it possible that some of what you’re going through right now might be self-inflicted?

Tarot is a card game; one of the earliest card games. Apparently, it’s a bit like bridge

I think tarot works, but it doesn’t work for any particularly mystical reason. The cards themselves are not very old, and they’re not very esoteric either. People have made various claims about their mysterious origin — in ancient Egypt, or the court of King Arthur, or Atlantis — but in fact it isn’t really so much of a mystery at all. To produce a deck of cards, you need paper and the printing press, both of which are Chinese inventions, so it’s unsurprising that the earliest ancestors of the tarot appear in Tang-dynasty China. From there the system spread through Persia and the Middle East before finally arriving in Europe sometime in the fourteenth century. But they weren’t for telling the future. They were for playing cards.

Tarot is a card game; one of the earliest card games. Apparently, it’s a bit like bridge; the main difference is that it has an extra suit of twenty-one or twenty-two numbered trump cards, known as trionfi or tarocchi, which means triumphs. These were decorated with a host of portentous images. Some cardmakers preferred classical deities. Saturn eating his children, the Sun in his chariot, Mercury in his winged hat. Others went for chaste female figures representing the arts and sciences: poetry, philosophy, geometry. Or even chaster female figures representing Christian virtues: faith, hope, industry, loyalty. Most decks were a mishmash of all of these and more. Mars, Venus, the Pope, the Emperor, Death, a miser, a boat, a bashful-looking elephant. Aristocrats would commission hand-painted decks, in which the trump cards were essentially miniature icons, beautifully realized and edged in gilt. It didn’t really matter what they represented; the game played the same. In the plague years of early modern Europe, a lot of tarot decks feature Death, grinning horribly on his white horse, trampling kings and peasants alike beneath its hooves.

It’s hard to say exactly when people started using these cards for divination, but it probably didn’t take long. Games and oracles have always been joined at the hip. The simplest oracle, and the simplest game, is flipping a coin: surrendering something to the invisible but all-knowing spirits of chance. The only difference is what you do next. You can decide that if it comes up heads, the gods are telling you to quit your job. Or you can decide that if it comes up heads, whoever guessed right gets to keep the coin. This is why gamblers are always superstitious: whenever you play cards or throw dice you’ve got one foot in the magical world. The ancient Israelites used to draw lots, and probably play forbidden games of chance, with black and white pebbles called the Urim and Thummim. But a set of Urim and Thummim were also kept in a special pocket in the High Priest’s apron. According to the Bible, there are three ways God communicates with ordinary human beings: through dreams, through prophets, and through those stones.

So the tarot was probably telling fortunes for hundreds of years before it was officially inducted into the esoteric toolkit. That happened in 1781, and it was done by Antoine Court de Gébelin. De Gébelin was maybe the first to take a very popular path. He’d started out as a liberal revolutionary, a freemason and a friend of Benjamin Franklin. Eventually he got bored of politics and started messing around with esoterica instead. One day, he witnessed two women playing tarot; immediately he intuited that “the form, the disposition, the arrangement of this game, and the figures which it presents, are so obviously allegorical, and these allegories are so in conformity with the civil, philosophical and religious doctrines of the ancient Egyptians, that one cannot avoid recognizing the work of these sagacious people: they only could be its inventors.” De Gébelin imagined tarot must have begun as the Book of Thoth, which described the creation of the universe and the origin of the virtues. Originally, the images of the tarot had inlaid the dome of a great Egyptian temple. When their civilization crumbled, the magi of Egypt turned them into cards and dispersed them around the world, so the knowledge they’d guarded would not be lost for ever.

I think tarot works, but it doesn’t work for any particularly mystical reason

De Gébelin wasn’t the only person to come up with a grand theory of tarot. In the nineteenth century, the Rosicrucian and Christian Kabbalist Éliphas Lévi Zahed noticed that the twenty-two trump cards — which are, in divinatory tarot, called the Major Arcana — corresponded to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet: clearly, the tarot was actually Jewish in origin. Later, the folklorist Jessie Weston decided that the tarot was actually an expression of her great occult interest, which was the Grail legend. The suit of cups represents the Holy Grail, the wands are the Lance of Longinus, and so on. But it’s de Gébelin’s mad interpretation that turned out to be the most influential. When Pamela Colman Smith started composing the illustrations for the Rider-Waite tarot in the early twentieth century, everything was subtly Egyptified. In the seventeenth-century Tarot de Marseille, the Chariot is pulled by two horses; in the Rider-Waite it’s two sphinxes.

The occultists behind the Rider-Waite — and plenty of subsequent decks — thought that they were making the cards more meaningful. I’m not so sure. I think the cards work precisely because they’re ultimately arbitrary and meaningless, a set of pure symbols that allow us to play around with the interpretation of the world and think in ways we might not have thought before. A good tarot deck is one with plenty of weird details, but which trusts the reader to do that thinking by themselves.

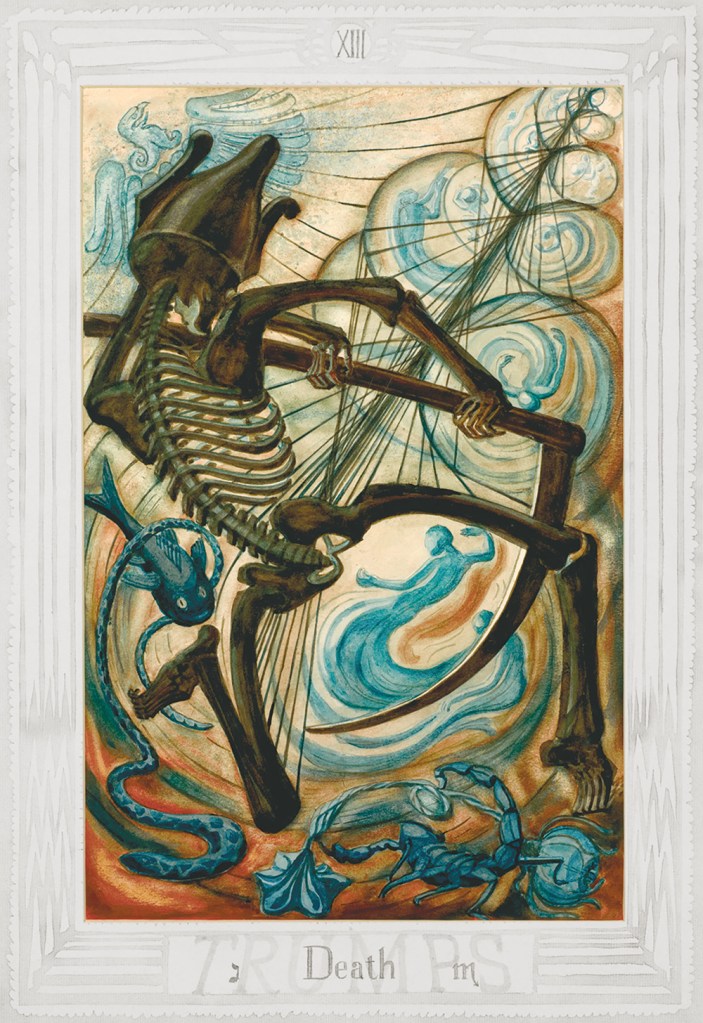

There are plenty of tarot decks on display at the Warburg Institute’s Tarot: Origins & Afterlives. Some gorgeous, gilded early decks; woodcuts from Venice; hand-painted prototypes, all of which are magnificent works of art in themselves. There are also some of the original paintings for the 1943 Thoth Tarot, painted by Frieda Harris but commissioned by Aleister Crowley (or, as he preferred to be called, The Beast 666). The Thoth Tarot is a system of bizarre vorticist geometries in loud, screaming colors, full of motion and terror and strange esoteric symbols. The compositions are fantastic but forbidding: the Thoth cards practically spit on you for daring to interpret them.

The Thoth cards practically spit on you for daring to interpret them

After that, though, the exhibition goes off the rails. It ends with a “Tarotkammer,” displaying “a wide-ranging collection of tarot decks by today’s artists and collectives.” They are, almost without exception, awful. A feminist tarot featuring the images of Sara Ahmed, Audre Lorde and Hannah Arendt. A “lockdown Tarot” featuring a portrait of Donald Trump as the “King of Vaccines” and Jacob Rees-Mogg as the Devil. There’s no room for interpretation in these cards; they tell you exactly what they stand for, and exactly what they think. The worst is a deck made as “a creative tool to guide conversations and discussions about a future Barrow-in-Furness.” One of the cards features a wobbly line drawing of a camera, surrounded by the words “CULTURE – MEDIA – OPPORTUNITY – SIGNAL – FILM INNOVATION – DIGITAL FUTURES.” This is one way of representing these things. But I think I’ll keep the Knight of Swords, speeding into a landscape gone blurry, all movement, as his horse’s eyes roll back in terror.

Tarot – Origins & Afterlives is at London’s Warburg Institute until April 30.

Leave a Reply