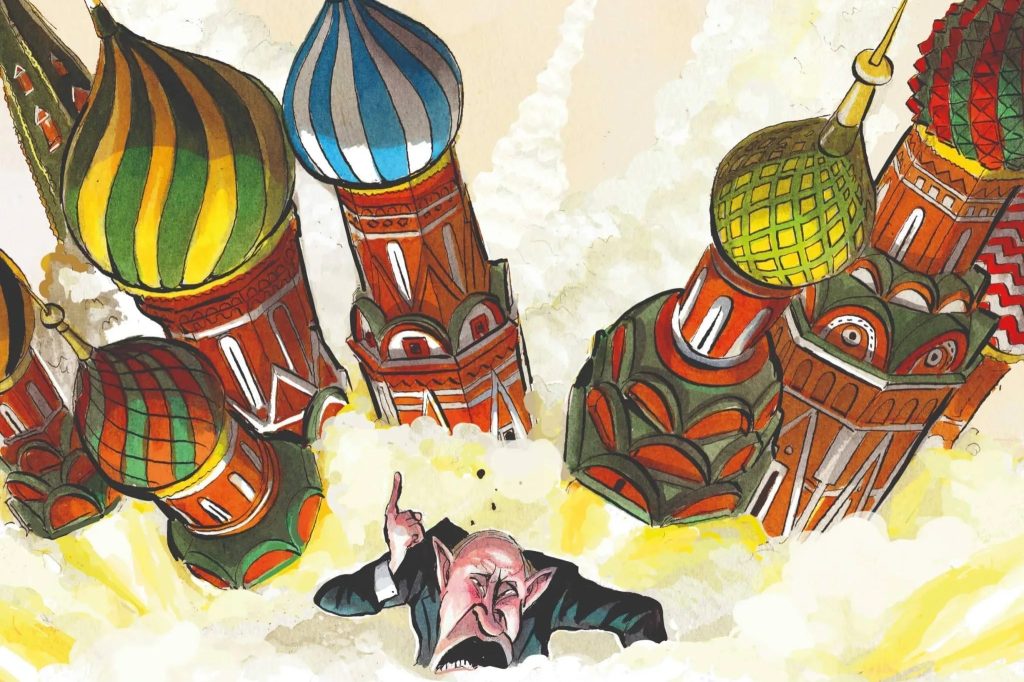

Vladimir Putin has announced that Moscow’s nuclear doctrine will be adjusted, telling a group of senior officials that Russia could use nuclear weapons if it is attacked using conventional weapons.

Inevitably there is concern that Putin could resort to a nuclear strike on Europe if western assistance to Ukraine crosses certain red lines.

Putin’s remarks took place on September 25, when the Russian Security Council held a meeting to discuss Russia’s nuclear deterrence posture. The Russian President said that the doctrine will be updated so that if a non-nuclear state attacks with the cooperation of a nuclear state, it will be seen as a joint attack. And Russia will consider a nuclear strike once:

we receive reliable information about a massive launch of air and space attack weapons and their crossing our state border. I mean strategic and tactical aircraft, cruise missiles, UAVs, hypersonic and other aircraft.

We reserve the right to use nuclear weapons in the event of aggression against Russia and Belarus as a member of the Union State.

A nuclear doctrine is a formal policy that outlines a country’s principles, strategies, and conditions for the deployment and use of nuclear weapons.

Before judging the significance of Putin’s remarks, it is worth keeping two things in mind. First, while constituting a formal policy, nuclear doctrines are not ironclad laws of statecraft that determine when a state will resort to using nuclear weapons. In reality, the decision always comes down to a world leader who will decide whether or not to press the proverbial red button.

Second, and relatedly, nuclear doctrines are purposefully vague. In other words, it is important to leave your adversaries guessing as to when the threshold for a nuclear response might be crossed.

Whether or not Russia will launch a nuclear strike at Nato or Ukraine boils down to whether Putin believes he has more to gain from nuclear weapons than he has to lose. If he thinks a nuclear strike is warranted and beneficial, he will find a way to justify it in terms of Russia’s nuclear doctrine. This was already the case with the old doctrine and will not change, just because the doctrine has been revised.

The announced doctrine change is therefore less about a fundamental change in Russian nuclear policy and more about a signaling effort to western audiences. Moscow wants to make it clear to London, Berlin, Washington D.C. and other western capitals that the nuclear option is explicitly on the table, and that by continuing to increase assistance to Ukraine, these countries raise the risk of nuclear weapons being used.

This is of course particularly relevant in the context of the ongoing discussion about allowing Ukraine to use western missile systems, such as the British Storm Shadow and American ATACMS, to strike targets deep inside Russia, which Russia wants to prevent. Given that Russian saber rattling has prevented or significantly slowed the provision of crucial aid to Ukraine in the past, it makes sense that Russia is doing this once again.

In the end, however, Russian nuclear weapon use remains unlikely — at least for the moment. If Russia were to seriously consider using nuclear weapons in Ukraine or against Nato countries, there would be warning signs. For example, the family members of Russian oligarchs, who continue to enjoy the high life in European capitals, would start leaving Europe in large numbers. It’s hard to imagine Putin initiating a nuclear war with Nato while endangering the relatives of his key supporters in Russia.

In addition, if a nuclear strike was on the table, it would likely be preceded by movements of tactical nuclear warheads from storage sites to forward-deployed bases to shorten the time between a potential decision and the launch of a non-strategic nuclear weapon. In addition, Russia would start parading nuclear-armed missiles in an effort to increase pressure on western supporters of Ukraine to stop their assistance before the war escalates.

At the moment, there have been no such movements or deployments. On the contrary, Putin has been extremely careful in his signaling efforts not to cross certain thresholds to avoid angering his international partners, especially China. Beijing has repeatedly made it clear that it does not condone Russia’s nuclear threats and is not interested in a nuclear war between Nato and Russia.

As such, the West should respond calmly to Russian nuclear threats, including any potential changes in doctrine that may emerge in the coming days or weeks. Panic is unnecessary, and we should not succumb to nuclear blackmail.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply