The general secretary of China’s Communist Party is a different kind of leader. Now in his third five-year term, Xi Jinping believes that time is running out for him to secure his legacy as Mao Zedong’s true successor. He spent a decade dismantling the technocracy and politburo consensus government ushered in by Deng Xiaoping after Mao’s death, rolled back the authority of local party nomenklatura in favor of more centralized control from Beijing, and worked to subordinate China’s economy to the Communist Party’s (meaning Xi’s) political priorities.

In abandoning the “to get rich is glorious” social contract of the post-Tiananmen Square era, Xi has come to bury Deng and not to praise him. Or, perhaps, to transcend him, as appeared to be the outcome of the sixth plenary session of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee in November 2021. For only the third time in the party’s hundred-year history — the first in 1945 before Mao’s victory in China’s Civil War and the second in 1981 under Deng that rejected certain excesses of the Cultural Revolution — the Committee passed a resolution “on certain historical questions” related to Communist Chinese socialism.

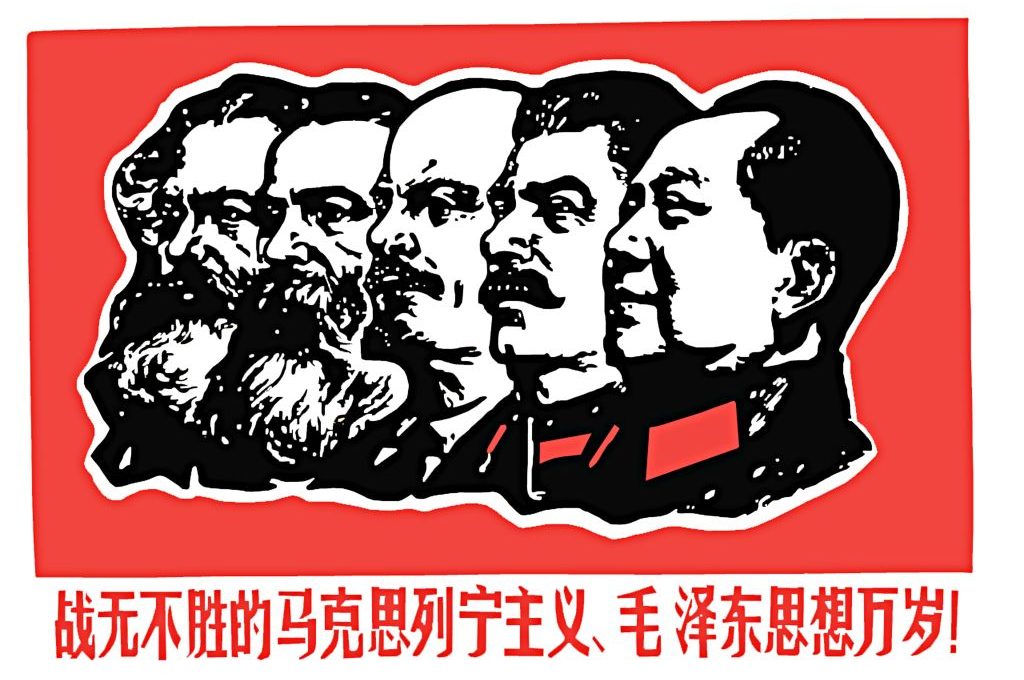

The 2021 resolution not only elevated Xi’s vision for the Communist Party and state to a level with Mao and Deng, but also replaced Deng’s conception of Communist China’s history and approach to the transfer of power. The party’s official position became that China under Xi is undergoing its third great development phase — the first, under Mao’s original socialist theory, brought the Communists to power and the second, under Deng and his modifications to Mao’s theory, made the country richer. Xi’s ideas, in turn, seek to make China strong. Deng was, in effect, a bridge between Mao and Xi. And in a nod to Xi’s personal dictatorship, the resolution omitted references to power transfers among succeeding generations of Party leaders after Mao.

Xi’s new course would be less concerning if it looked like he was consolidating power for its own sake or merely hoping to enjoy his position at the top of the Communist Party’s greasy pole. Unfortunately, far from being China’s own Brezhnev, Xi is coming to more closely resemble Stalin in the lead-up to World War Two. Starting from a momentous strategic shift in 1928 and culminating in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Stalin put a draconian policy program in motion to facilitate a major European war that would serve as a catalyst for the Soviet Union to impose its will across the continent. Xi, in pursuing Communist China’s hegemony in Eurasia, is following a similar path.

For Stalin, the road to war began almost as soon as he became general secretary after Lenin’s death. Bruised by the Red Army’s military defeat in Poland and failure to bring the socialist revolution to the heart of Europe, Stalin was alarmed by the inability of Soviet-allied communist parties (which took orders from the Communist International, or Comintern in Moscow) to gain power on their own through democratic means. So, in July 1928, the Comintern’s Sixth Congress adopted a landmark resolution that designated Europe’s social democrats as “social fascists” against whom communists were to wage all-out war. A month after the Congress, Stalin announced the start of the first Five-Year Plan — collectivization of agriculture and a ruthless class war against the Soviet Union’s more productive peasants would yield grain to export for hard currency, which Moscow would spend on developing heavy industry and mass producing dual-use machinery. Postulating that an army’s main strength lies not in its weaponry or commanders, but rather in the rightness of its government’s political direction, Stalin then proceeded to thoroughly purge the Red Army as events moved closer to war.

Many at the time did not see Stalin’s moves as intertwined, when in fact they were tied up with his burning desire to succeed where Lenin failed and win the war that Lenin lost. By forbidding Germany’s Communist Party, then Europe’s strongest, from politically allying with its Social Democrats, Stalin helped pave Hitler’s path to power as someone who could (and promptly did) upend the post-World War One Versailles peace settlement. The Five-Year Plan was a screen to hide a massive rearmament drive to get the Red Army ready for war and the purges turned that army into Stalin’s political instrument unable to block his militarist designs. Political consolidation at home, destabilization abroad and the subordination of the economy to ideological objectives: Stalin’s administrative inheritance passed on to Mao and embraced by Xi with adjustment for the twenty-first century.

Xi’s domestic position is secure, but he is doubtless concerned about mounting structural problems that could weaken his ability to achieve his political goals. China’s population is falling and its growth slowing, so Xi has increased the Communist Party’s direct control over the economy, and upped its campaign of destabilization abroad — prematurely ending one country/two systems in Hong Kong, provoking border clashes with India, accelerating the militarization of the South China Sea, escalating against Taiwan and filling power vacuums left by the United States — while continuing to expand and modernize what is already the world’s largest army and world’s largest navy. America remains institutionally unable to compete with China’s overseas infrastructure development and direct investment initiatives, and Xi has worked to weaken America’s diplomatic soft power with his brokering of Saudi-Iranian rapprochement and floating mediation of the Ukraine War.

Stalin resolved to foist his regime on Europe at gunpoint after his allies failed to do it peacefully. If, short of war, America can be maneuvered into accepting China’s hegemony in Eurasia and is bereft of local partners willing to militarily confront or economically resist Beijing, then so much the better for Xi. In that sense, he is not only following in Stalin’s footsteps and looking to overtake Mao, but is operating in the best traditions of Sun Tzu.

That Xi is an ideologue committed to moving heaven and earth to achieve his ends, and willing to subordinate economy, society, state and the Chinese Communist Party to those ends, makes the threat to America and its allies especially acute. A technocrat who prioritizes a social contract or a kleptocrat who relishes the perks of power is easier to manage. Just as the western powers eighty years ago reacted to, but could not derail, Hitler’s and Stalin’s drive toward war, Washington finds itself waiting to see where the history-altering blow from China will fall. America can either react to the crisis when it comes or adopt a new and much more proactive strategy to get ahead of Xi and succeed where our forebears in earlier times failed. Xi’s window of opportunity is closing.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.