Hamas has achieved something that no Arab army has done since the 1948 war: captured several Israeli localities and held them for hours. Yet the magnitude of this initial success, in which they took Israel by complete surprise having lulled its famed intelligence services into false complacency, may prove a double-edged sword.

Yes, they have a huge bargaining chip, with as many as fifty civilians and soldiers believed to have been captured and taken to Gaza, many of them women and children. But it is likely now that Israel will end its decade-long policy of containment in favor of an attempt to totally destroy Hamas’s military capabilities, despite the possible escalation of such a move to a wider regional conflagration.

Hamas’s latest aggression may well have driven the final nail in the coffin of the two-state solution. For one thing, while most Israelis have been disabused of the idea by Yasser Arafat’s war of terror (euphemized as “al-Aqsa Intifada”) and the subsequent confrontations with Hamas, Saturday’s horrendous massacres may convince other international players of the mortal dangers that would follow if Israel withdraws from key West Bank areas (which would be needed for a viable Palestinian state to exist).

Hamas’s latest aggression may well have driven the final nail in the coffin of the two-state solution

After all, were such an invasion to ensue from a West Bank state, hordes of terrorists would be able to roam the more populous streets of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in no time. What do two-state solution campaigners believe would happen then? What sovereign state could possibly allow a situation that would arise in which their citizens could be indiscriminately slaughtered on its streets?

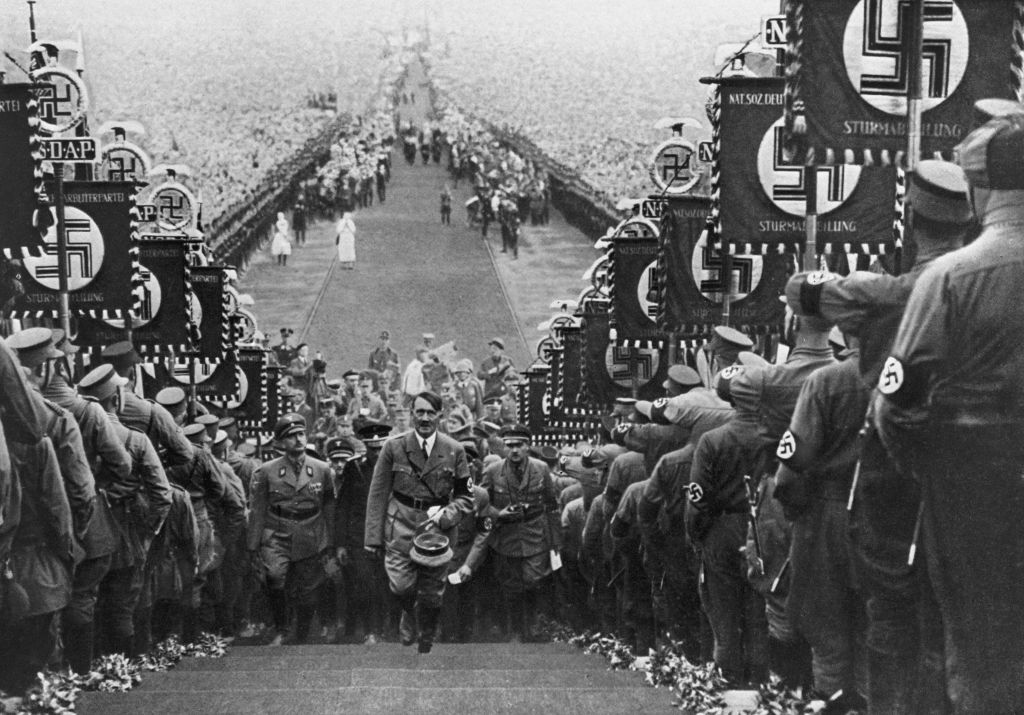

What’s more, the grim brutality of Hamas’s recent atrocities may also draw international attention to the corrupt and oppressive nature of its regime. And just as the creation of free and democratic societies in Germany and Japan after World War Two necessitated a comprehensive sociopolitical and educational transformation, so long as the West Bank and Gaza continue to be governed by Hamas’s (and the PLO’s) rule of the jungle, no Palestinian civil society, let alone a viable state, can possibly develop there.

The eminent British historian A.J.P. Taylor quipped that “Wars are much like road accidents. They have a general cause and particular causes at the same time.” As far as the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is concerned, the general cause stretches back to the century-long rejection of the Jewish right to statehood. At a more immediate level, the origin of the latest confrontation can be traced to the Oslo Accords of 1993-95, which the Rabin-Peres government viewed as a pathway to peace but the Palestinian leadership considered a “Trojan Horse” (to use the words of prominent PLO official Faisal Husseini) designed to bring about Israel’s demise.

Rather than use the end of Israel’s “occupation” as a springboard for bringing the Oslo process to fruition (control of the Gaza and West Bank Palestinian population was transferred to the PLO-dominated Palestinian Authority in May 1994 and January 1996 respectively), terrorism in these territories spiraled to its highest level since their capture by Israel in the 1967 war.

By the time of Yasser Arafat’s death in November 2004, his war of terror — the bloodiest and most destructive confrontation between Israelis and Palestinians since 1948 — had exacted 1,028 Israeli lives: nine times the average terrorist death toll in the pre-Oslo era. Yet, while Israel destroyed the West Bank’s terror infrastructure in a sustained four-year counterterrorism campaign, Hamas managed to keep its Gaza infrastructure largely intact despite the targeted killing of many of its top leaders. Reverting to massive rocket attacks on Israeli cities and villages, especially after its violent takeover of the Strip in the summer of 2007, Hamas drove Israel into four inconclusive wars in an attempt to stop these relentless attacks: in December 2008-January 2009, November 2012, July-August 2014, and May 2021. But the latest conflagration may prove one war too many.

Shortly after the September 1993 signing of the first PLO-Israel accord, Oslo’s chief architect Yossi Beilin arrogantly prophesied that “the greatest test of the accord will not be in the intellectual sphere, but will rather be a test of blood.” Should there be no significant drop in the level of violence and terrorism “within a reasonable period of time” after the formation of the Palestinian Authority, he argued, the process would be considered a failure, “and should there be no choice, the IDF will return to those places which it is about to leave in the coming months.”

Thirty years and thousands of deaths later, with Saturday’s 400 (though some estimates suggest it could be as high as 600) fatalities four times as large as the 9/11 death toll in relative terms, Israel seems to be finally coming to terms with the abysmal failure of Oslo’s “test of blood.”

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.